Insight Email Vol-2 No. 3

This ISP Insight Email Vol.2. No.3 (English version) is published on February 29, 2024 as a translation of the original Burmese version published on February 25, 2024.

EDITOR’S NOTE

This week’s ISP Insight Email revisits “Naypyitawlogy” by examining the administrative restructuring of the State Administration Council (SAC) during its three-year reign. In literature of political science, scholars often study the relationship between an authoritarian regime’s stability and state capacity. Particularly, these studies often look at the size of the cabinet and the volatility and terms of the cabinet members. The African continent has been a prominent focus for research in this area due to the prevalence of flourishing authoritarian regimes. The SAC’s unstable administration should be studied in comparison with some of those authoritarian regimes in Africa.

The structure of the SAC remains volatile, with frequent reshuffles including reassignment, new appointment, dismissal, and transfer. Currently, these changes have affected 152 individuals encompassing the Council Members, the Cabinet Ministers, and other high-ranking positions at Union and State/Region levels. Three years have passed but many positions within the cabinet and high-level authorities remain inconsistent for the SAC-led regime in Myanmar.

Our Trends to Watch section examines the “Thailand’s Humanitarian Diplomacy,” where the initiative’s potential effectiveness is analyzed. Thailand’s Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs, Parnpree Bahiddha-nukara, proposed a new aid strategy towards Myanmar focused on humanitarian support and relief efforts as a mean to promote humanitarian diplomacy. This humanitarian initiative would involve bilateral governmental collaboration, as well as the participation of the Red Cross organizations from both Thailand and Myanmar.

In this week’s What ISP is Reading section, we introduce a website called “The Borderlens: Beyond the Lines,” which publishes detailed accounts on Myanmar’s current affairs, including the most recent noteworthy events at the Manipur and Mizoram borders, the crash of a plane retrieving the junta’s soldiers who fled across the border, and the ongoing battles in northern Shan State.

KEY TAKEAWAY

Naypyitawlogy – 4

SAC’s Rickety Administration

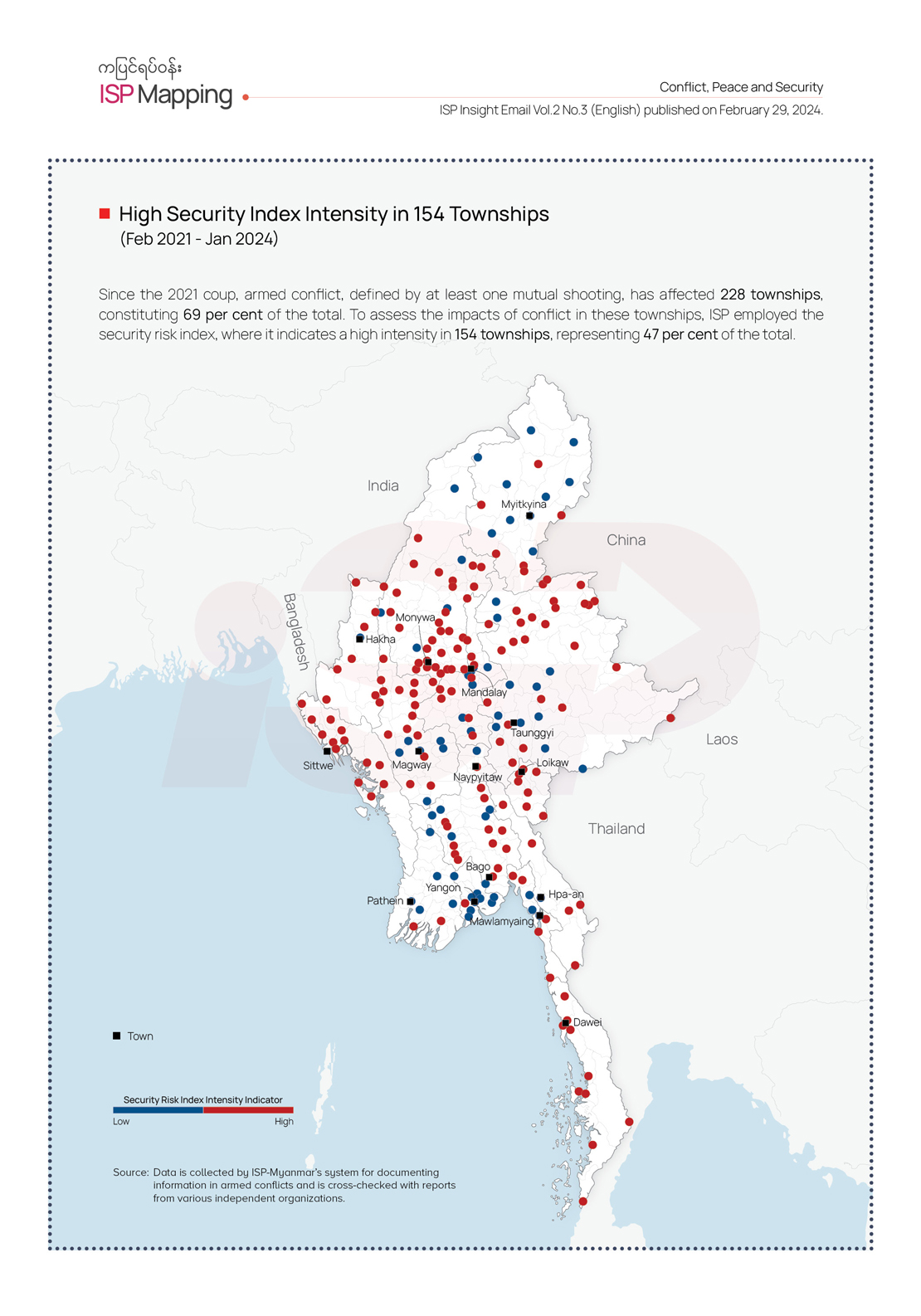

In three years, the junta’s decisions regarding top-level position reshuffles resulted in the involvement of 152 individuals in his administration. This context should be studied in comparison with the authoritarian regimes in Africa.

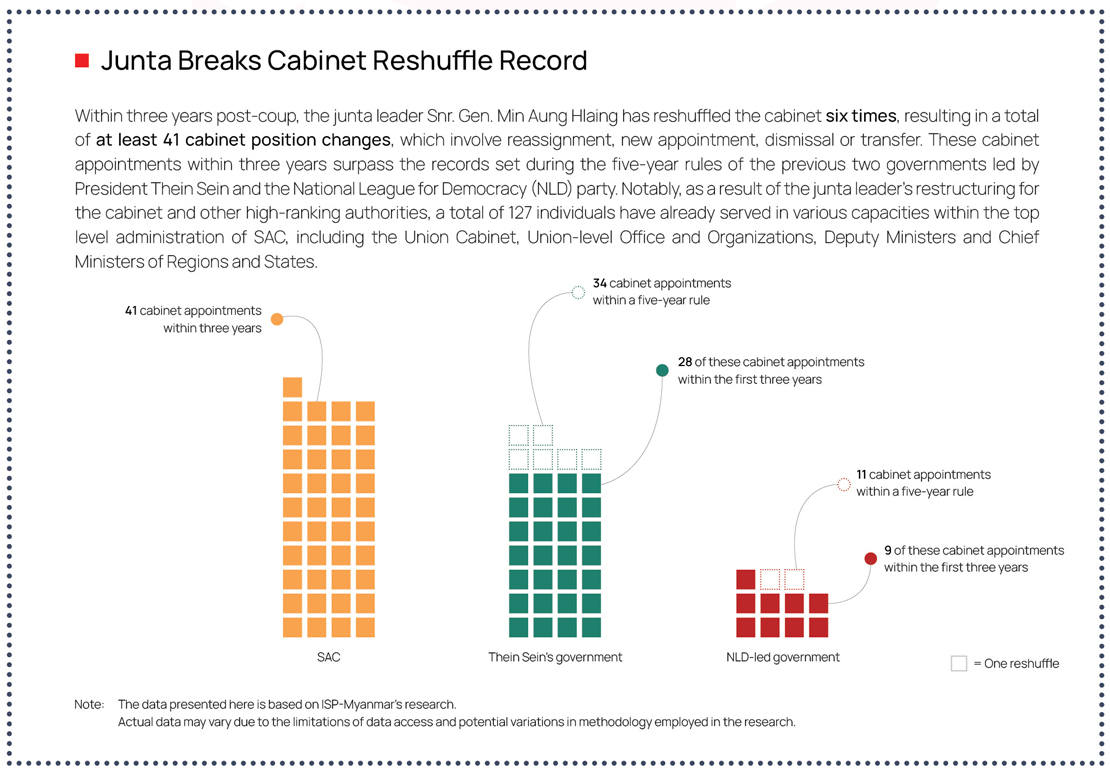

Three years following the 2021 coup, the junta-led administration has yet to establish a stable structure. With several reshuffles within the council itself, as well as among the cabinet members and deputy ministers, the SAC has broken the records of the former Thein Sein-led and NLD-led governments. Hence, this week’s ISP Insight Email will attempt to delve into “Naypyitawlogy” with the focus on “SAC’s Rickety Administration.” Additionally, we find it pertinent to compare the SAC’s unstable administrative structure with some authoritarian regimes in the African continent.

Examining the SAC’s administrative structure requires a close assessment of its decision-making processes, rule-setting and enforcement mechanisms, which aim at maintaining order, achieving objectives, and addressing the needs of the nation’s citizens. Following the 2021 coup, the military leadership justified its actions in accordance with the 2008 Constitution, promising a free general election. A Five-Point Roadmap was unveiled, prioritizing scrutiny of previous ballot errors, Covid-19 prevention measures, economic recovery initiatives, implementation of peace set out in the National Ceasefire Agreement (NCA), and scheduling the election. However, this Roadmap underwent a shift in 2023, when the SAC put priorities of national stability and food security as national objectives. Subsequently, in September of that year, the emphasis returned to organizing a free and fair multi-party democratic election. However, neither an election date nor implementation procedures have yet been proposed. Although the SAC took control of power using the 2008 constitution in 2021, it failed to fulfill its own promises to establish stability in the “state emergency” within the first year. Eventually, it has repeatedly extended the six-month military rule for five times citing the “unusual circumstances of the country” as justification.

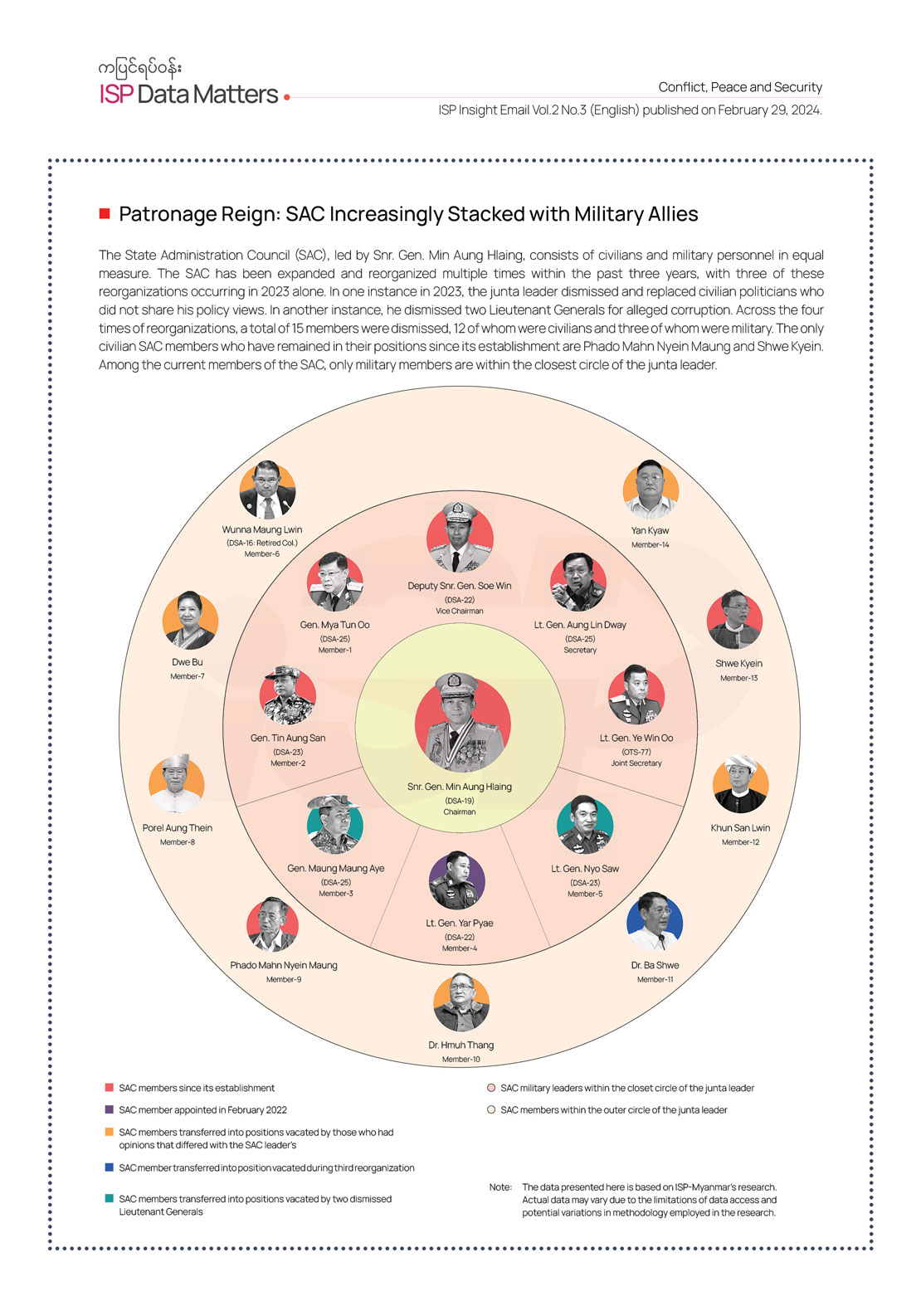

When the SAC was founded as the leading council at the beginning of the coup, it started with a depiction of half military and half civilian personnel in composition1. The composition of the council inclines to an anti-NLD alliance. The generals selected some council members from the leaders of the 34 political parties whom they met before the 2020 election, as those who had been displeased with the NLD government’s actions. There is no question that Snr. Gen. Min Aung Hlaing holds the veto, he desires to portray a collective leadership initially.

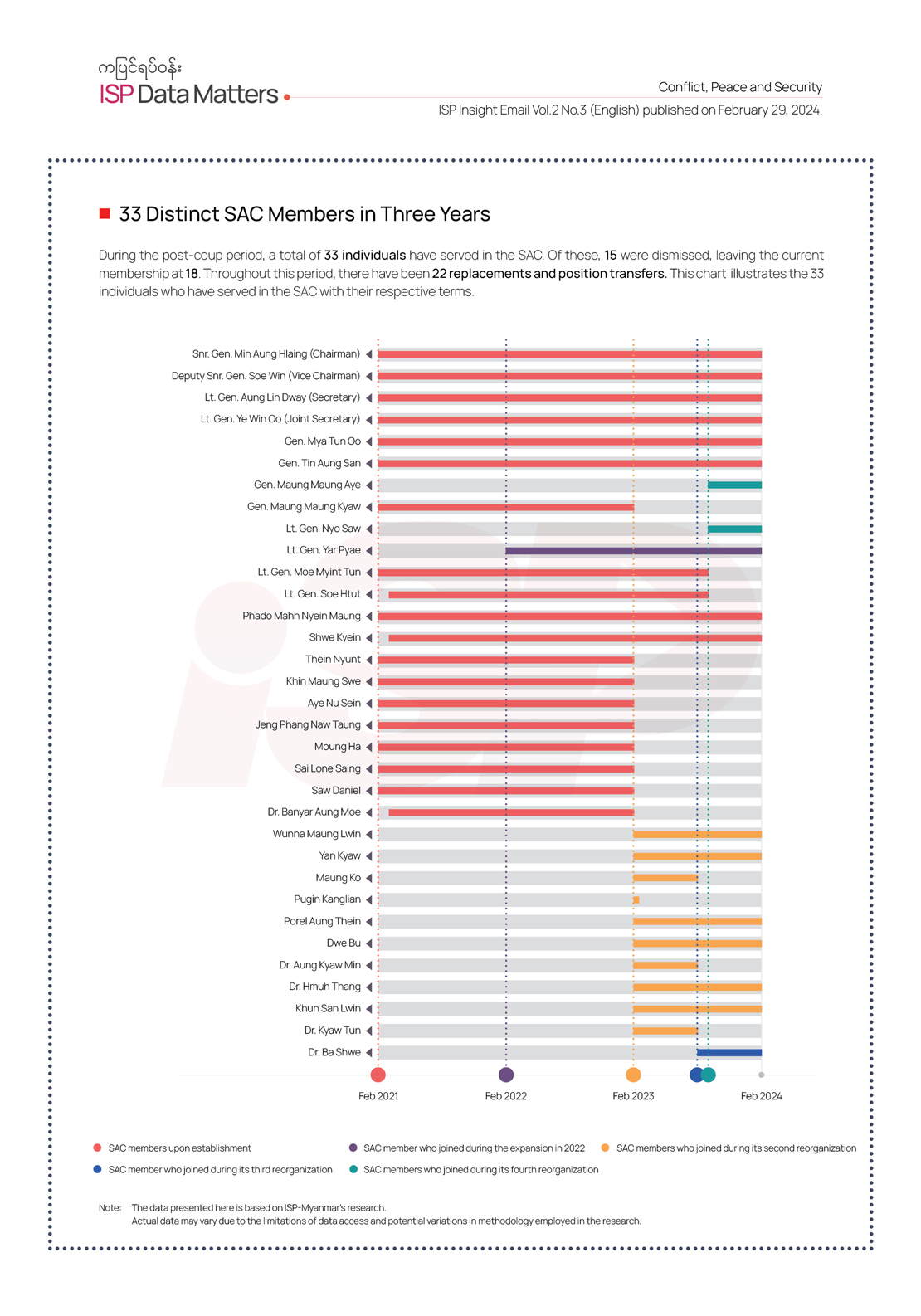

The SAC has undergone many reshuffles during the three years since the coup, with 15 dismissals of council members and 22 replacements. During its inception on February 2, 2021, the SAC was founded with 11 members: eight military personnel and three civilians. One day later, five civilians were added, and within another month, two additional civilians and a Lt. Gen. joined, bringing the total to 19 members. Another Lt. Gen. was added on February 8, 2022, bringing the total to 20, with 10 military and 10 civilian members.

In 2023 alone, the SAC underwent three reshuffles. The first reshuffle on February 1 involved the replacement and removal of civilian politicians who did not see eye to eye with the junta leader. Even more civilian components were removed during the second reshuffle on August 2, from the council. In the third reform on September 25, two Lt. Gen, trusted members of the junta leader, were dismissed due to corruption charges, and substituted with two other military officials. In extending their rule in as the last in February 2024, no changes to the SAC members were observed. Throughout a three-year reign, the SAC has gone through a total of 33 changes in different individuals, with only eight lasting the full duration. Among these eight, Phado Mahn Nyein Maung and Shwe Kyein are the sole remaining original civilian members2 of the council.

The SAC’s civilian members sacked during the reshuffle on February 1, 2023 was seemingly due to disagreements on the Political Parties Registration Law, which were proposed by the junta leader. Although these ousted members were later appointed as advisors, they no longer hold offices or departmental positions. In January 2024, nearly a year after the removal of council members in disagreement, the Political Parties Registration Law was revised again to be more lenient3. The former bar raised for the political parties seems unconducive to operate practically so finally the junta has to lower its standard. However, Snr. Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, the junta leader, has yet to provide any explanation regarding the amendment.

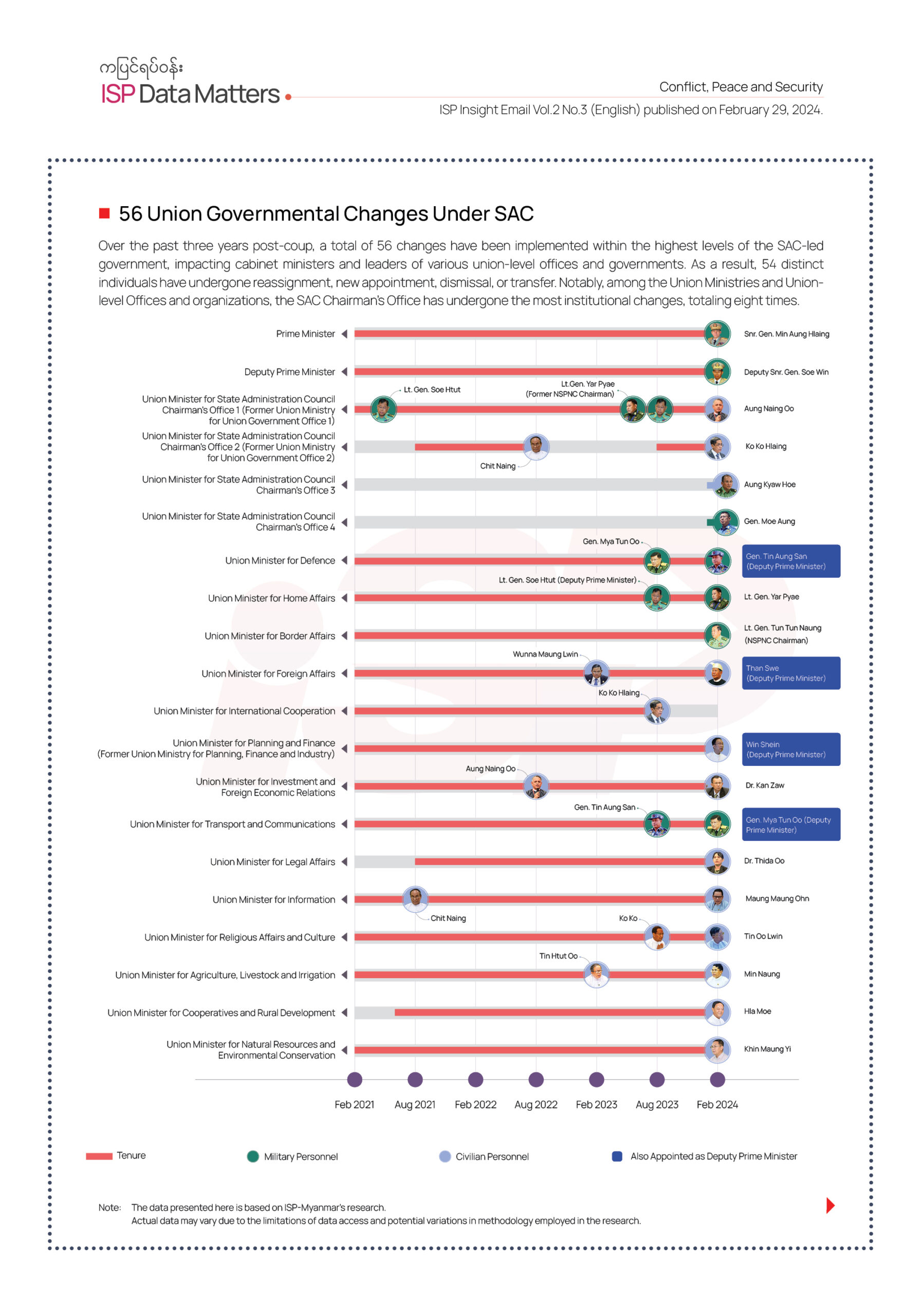

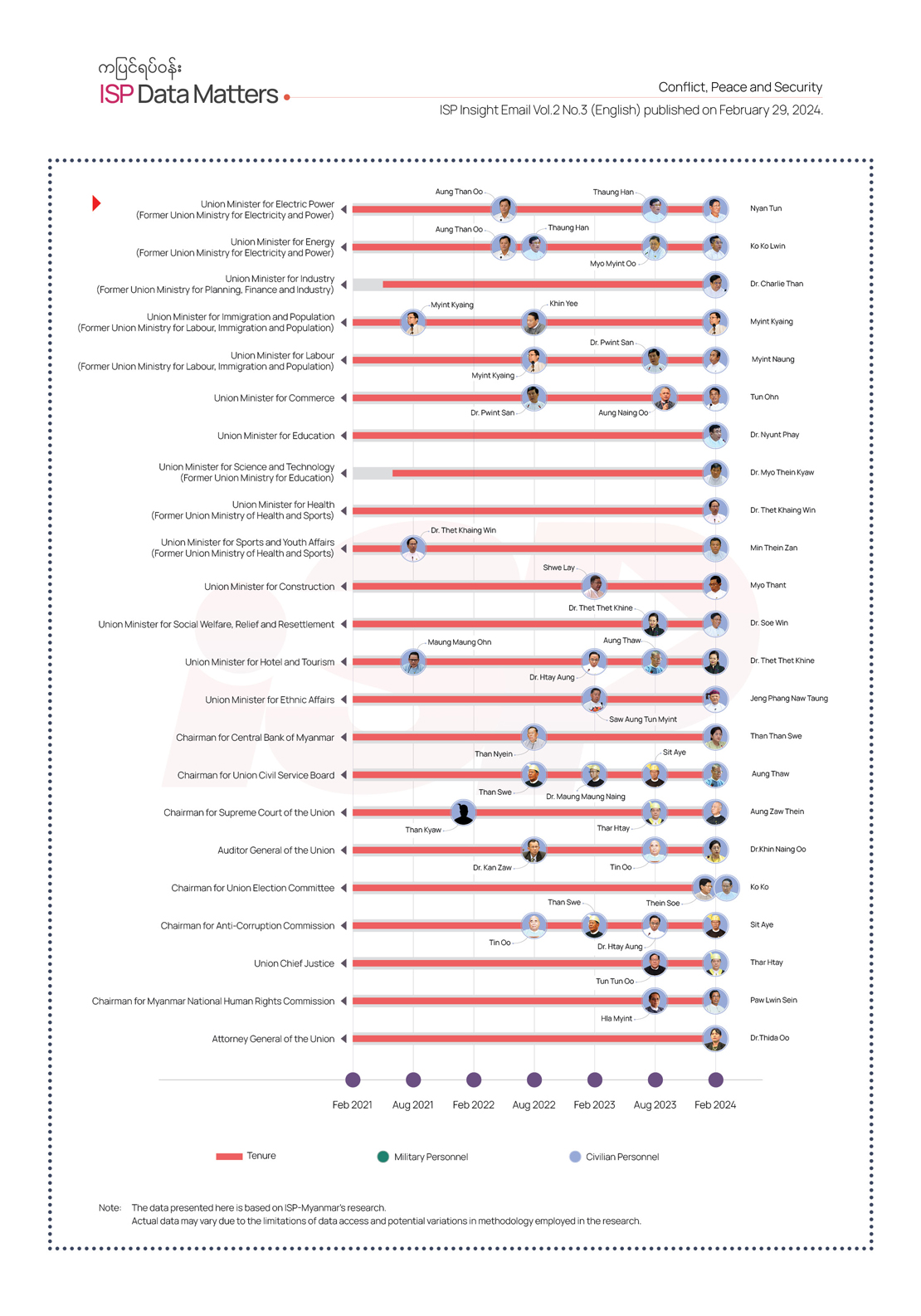

In addition to the reshuffles within the council, the SAC Chairman has orchestrated six reshuffles within the Union Cabinet, encompassing a total of 56 reassignments, new appointment, dismissal, or transfer. If the reshuffles for other higher administrative positions are included, a total of 152 individuals have been affected, spanning SAC members, Union Cabinet members, Deputy Ministers and Chief Ministers of States and Regions.

Among the ministries, the Ministry of Union Government Office underwent the most reforms totalling eight. The latest reform led to the separation of the State Administration Council Chairman’s Office Ministry No.1 to No. 4 from the original ministries. At the initial formation of these four ministries, the SAC Chair Office No.3 and No.4 lacked designated ministers, leading to the subsequent appointments of ministers at a later stage. These four newly established ministries will manage civilian administrative responsibilities under the SAC military leader’s purview. Snr. Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, who also assumed the role of Prime Minister, appointed an additional five Deputy Prime Ministers in 2023, bringing the total to six (and currently five following the removal of Lieutenant General Soe Htut). Second to the reform of the Ministry of Union Government Office are the Ministry of Energy, Ministry of Hotels and Tourism, Ministry of Labour, Union Civil Service Board and Anti-Corruption Commission which underwent three times of reform. The regime frequently changed the personnel to the point that as if they wanted everyone to enjoy a ministerial role.

Although the junta leader has formed the institutions in his regime, he does not seem to be relying on them (see Naypyitawlogy-1). For example, the National Solidarity and Peacemaking Negotiation Committee (NSPNC) was established in February 2021 to address peace-related matters but has convened only one official meeting in the past three years. When negotiating a ceasefire for the Operation 1027 with the Three Brotherhood Alliance (3BHA) in Kunming, China in December 2023, the institutional role of the NSPNC was almost non-existent. Instead of the NSPNC itself, the body’s secretary, Lt. Gen. Min Naing (OTS-66), was sent to attend the Kunming negotiation. ISP-Myanmar’s research indicates that there did not seem to be any well-defined proposals prepared by the Myanmar Armed Forces (MAF) side during the Kunming dialogues. Lt. Gen. Min Naing and officers from the Military Security Affairs (MSA) attended the first Kunming meeting. In the second meeting, alongside the former attendees, Gen. Moe Myint Swe (OTC-23), the junta leader’s aide-de-camp, was also in attendance.Therefore, it is evident that the junta leader is dealing things as personal matters and lacks confidence in the institutions he has established, demonstrating personal concerns. The SAC has also encountered challenges related to succession issues, stemming from the personal decisions of the junta leader (see Naypyitawlogy-2). Even worse, the junta leader might seem to perceive that the crucial responsibilities should be delegated solely to his protégés.

There now appears to be no political exit for the junta leader. While the election is prioritized, many steps remain to be implemented, including conducting a national census in 2024, and preparing a list of eligible voters. In the meantime, the junta has tagged several adjectives to his promised general elections such as “free, fair, and credible” and “without a gap in constituencies.” In fact, the junta leader himself has obstructed any potential political exit from the current situation. In March 2023, more than 40 political parties, including the National League for Democracy (NLD), were dissolved. Aung San Suu Kyi was sentenced to a lengthy prison term, and was barred from meeting with international diplomats, unlike previous military regimes and in stubborn disregard to the ASEAN Five-Point Consensus (5PC). The relations with Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs) have deteriorated further, and the junta leader blames many failures to the EAOs. The Conscription Law recently activated has become a liability to national development and economic productivity is now at further risk, impeding the potential for Myanmar to chart a positive trajectory for generations to come (see ISP OnPoint 20). Snr. Gen. Min Aung Hlaing’s approach to managing the economy is also arbitrary and ad hoc. This issue will be further explored in our upcoming Naypyitawlogy series.

The relationships between the stability of authoritarian regimes and state capacity are widely studied in political science, often through the analysis of the sizes and volatility of the regime’s cabinet. The African continent, home to numerous dictators, serves as an important area of study for regime stability and their regime size. For instance, the average cabinet size in Cameroon is 40 members, while Congo has 38 members. In 2017, the average cabinet count for the African continent was 29. Countries experiencing substantial ministerial changes include the Central African Republic (32 per cent), the Democratic Republic of Congo (29 per cent), and Nigeria (26 per cent). Zimbabwe, during Mugabe’s era, became notorious for unpredictable reforms of cabinet. In authoritarian African nations, exclusive politics often correlates with high levels of violence, widespread corruption, and loss of legitimacy.

The SAC of Myanmar can be compared to some dictatorial regimes in Africa. During its three-year reign, significant reshuffling of ministers and council members has occurred, reflecting institutional volatility. Political instability, inconsistent leadership, arbitrary decision-making, fluctuating policies, and intensifying patron-client relationships within the SAC-led institutions can disrupt information flow, posing a risk of institutional collapse.

SPOTLIGHTS

The “Spotlights” section aims to provide a succinct overview of recent noteworthy developments. Three compelling issues from the past two weeks will be discussed.

Yakuza/Broker and Myanmar

The United States filed a fresh indictment against Yakuza boss Takeshi Ebisawa on February 21,2024. The indictment involves alleged discussions with a leader of an EAO in Myanmar, in which the exchange of uranium and plutonium, crucial elements for nuclear development, with anti-aircraft weapons and other armaments. Ebisawa was initially arrested in April 2022 and faced charges under international drug and arms smuggling laws. Subsequently, he is now accused once again, this time with conspiracy to traffic nuclear materials. At the time of his initial arrest, Ebisawa was allegedly serving as a broker to procure weapons for the ethnic forces in Myanmar and news reports also indicate additional agreements involving the exchange of money for the weapons, as well as drugs. When the indictment was filed in 2022, the report included information about the involvement of the chairman of the Restoration Council of Shan State (RCSS).

Conscription Forces Destitution

The Conscription Law enacted by the SAC has triggered a widespread panic among the people of Myanmar. Many youth feel the urge to leave the country immediately and are queuing up to apply for passports. The queues start forming as early as midnight, well ahead of office hours. Two women reportedly died of suffocation in a stampede at the passport office in Mandalay. Thailand, a sanctuary destination for Myanmar citizens, is alarmed about a mass exodus, and the Prime Minister of Thailand himself has warned that actions will be taken against those entering illegally. Meanwhile, reports indicate that revolutionary forces such as the People’s Defence Forces (PDF) have seen an increase in enlistment inquiries. At the same time, more soldiers are also being recruited by the EAOs, who are calling to join them instead of the SAC’s conscription. Forced recruitment remains prevalent in certain organizations, and some EAOs have reportedly warned that those who refuse to join may face the confiscation of their homes. Misfortunes never come alone, compounding the destitution faced by the people of Myanmar.

China’s Initiative in Rakhine Theatre

The Arakan Army (AA) has fully seized five townships as well as over 222 Myanmar Armed Forces (MAF) outposts in Rakhine State, while continuing their offensive in another five cities. One MAF aircraft and nine navy ships were also destroyed. The AA now also controls the entire Paletwa Township of Chin State, where India’s Kaladan Multimodal Tansit Transport Project is invested. Over 700 MAF soldiers have fled over the border to India and Bangladesh. As a response to such frequent illegal border crossings, India has declared its intention to build fences along the borders, while Bangladesh has announced that it will no longer accept individuals from Myanmar, considering that they have already accommodated about a million Rohingyas refugees. As the conflict has extended beyond the southern part of the state where significant Chinese projects are underway, China has seemingly begun considering intervention. On the other hand, China’s initiative to repatriate Rohingyas from Bangladesh is on the verge of being halted. On January 28, during the meeting between the Chinese ambassador and Bangladesh’s foreign minister, the matter was discussed, and the ambassador appealed for patience regarding the delay. In an interview with BBC Burmese, the AA chief mentioned that they intend to persist in their mission and to explore ways to avoid a confrontation with China, which might intervene to prevent their major investment. The government of Bangladesh has strongly condemned the situation, as shells landed into its territory. The military council, facing setbacks in the ongoing conflict, held discussions with Indian counterparts in Naypyitaw on February 24 to enhance military cooperation between India and Myanmar. The political involvement of China in northern Shan State has apparently already led to a reduction of conflict.

TRENDS TO WATCH

Thailand’s Humanitarian Diplomacy

A humanitarian safe zone is planned to be established in Mae Sot on the Thailand-Myanmar border. However, officials have denied this to be a refugee camp.

Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister of Thailand, Mr. Parnpree Bahiddha-Nukara gave a speech at the World Economic Forum (WEF) held on January 16, 2024 which for the first time outlined Thailand’s policy regarding the Myanmar crisis.

One interesting component of Mr. Parnpree’s speech was Thailand’s offer to provide more humanitarian aid to Myanmar to reduce humanitarian sufferings and to promote humanitarian diplomacy with Myanmar. Not long after, on February 7-8, Mr. Parnpree visited the Thai-Myanmar border at Mae Sot and held discussions with Provincial Administrations and the 4th Army Area Commander.

A humanitarian safe zone he mentioned is planned to be built on the Mae Sot border by the end of this month. Though officials denied that this zone would be a refugee camp. Deputy Foreign Minister of Thailand, Sihasak Phuangketkeow, stated that food, medicine and other supplies will be distributed for an estimated 20,000 people and that the Thailand and Myanmar Red Cross teams will collaborate on implementing these aid efforts. He stated, “we don’t want to witness further destabilization in Myanmar,” emphasizing the need for the process to be “effective, credible, and transparent.”

Thailand’s initial plan to provide aid for 20,000 people would indicate an intention for a continuing aid to follow. Data indicates that over 2.6 million people have fled their homes in Myanmar since the onset of the current crisis. Thailand has quickly initiated advocating its plan. Shortly after the plan was proposed, on January 27 Mr. Parnpree met separately in Bangkok with both the Chinese Foreign Minister, Wang Yi, and National Security Advisor of the United States, Jake Sullivan where Myanmar was on both agendas. ASEAN Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance on disaster management (AHA Center) will be involved in both participation and monitoring capacities of humanitarian aids. Mr. Sihasak stated “My point is that this (the humanitarian aid plan) is for the people. Let’s not politicize this; if it turns out well, we can scale it up.” Thailand also hopes to hold dialogue with the SAC, EAOs and the opposition National Unity Government (NUG) through these humanitarian implementations. Hence the term “humanitarian diplomacy” is being used to describe Thailand’s position. Thailand preferred for the SAC to engage directly with ASEAN, while also facilitating open doors for Myanmar to engage in discussions with Brussels (EU), Delhi, Vientiane, Washington, and New York (UN).

Mr. Parnpree’s efforts at humanitarian diplomacy have already faced numerous criticisms. Former Foreign Minister of Thailand, Kasit Piromya, pointed out that this approach is misguided as it could serve to legitimize the Myanmar regime, and he believes the plan will have no impact on ultimately resolving the Myanmar crisis. Humanitarian diplomacy, as defined by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), involves decision-makers and policymakers who work full-time for the benefit of those affected while adhering to basic humanitarian principles. The ICRC’s diplomatic strategy aims to influence governments, non-governmental organizations, and civil society organizations involved in conflicts. This influence is achieved through long-term relationships and a focus on humanitarian issues.

International organizations, such as the ICRC, often negotiate with armed groups on humanitarian issues, and civilian staff members are usually also involved in managing and distributing aid in these negotiations. These negotiations also include protection of vulnerable populations in regard to aid provision issues, establishment of a humanitarian work field and observance of international laws.

To ensure effective aid provision, relief operations must be independently and impartially mandated between armed groups. This requires establishing good relationships and establishing institutional recognition in order to be able to work effectively. Thailand’s Foreign Minister has mentioned that the Myanmar conflict is complicated on multiple levels and that Myanmar risked becoming an arena for major-power competition. Whether the Thailand-led humanitarian initiative will be effective or if this initiative could find a political solution is an issue to be closely watched in the future.

WHAT ISP IS READING

The Borderlens: Beyond the Lines

As the world undergoes rapid changes, the security situation in India’s extreme eastern border regions is evolving swiftly as well.

This week we feature neither a book nor a report but a full website (https://www.borderlens.com/) that delves into the evolution of the conflicts and political dynamics along the borders of India, Myanmar, and Bangladesh in English. The founder of the website is the writer, journalist and social scientist, Mr. Bhidhayak Das. His X (Twitter) profile bio states that he is the CEO and the Editor of The Borderlens as well as a researcher/scholar engaged in peace studies and citizenship/statelessness studies in India and Southeast Asia.

The Borderlens is an independent and non-profit organization with an objective to cover articles related to the people of the eastern border region, including cultures, career issues, local economy, the environment, ecology, rivers and streams, trade and commerce, security, and geopolitics as well as storytelling in the border regions. Besides articles, the website also includes up-to-the-minute interviews, making it a highly informative resource. According to the website’s ‘About’ section, The Borderlens represents the culmination of several years of research, travel, and reconnaissance involving journalists, scholars, civil society members, and filmmakers from all over the country. This website showcases stories from the border regions of Southeast Asia and other continents. The website index presents the organization’s prioritization to present people as the focal point with the objective of The Borderlens being to bring to the forefront the diverse dimensions of life along our borders and beyond.

As the world undergoes rapid changes, the security situation in India’s extreme eastern border regions is evolving swiftly as well. Moreover, the geopolitical shifts and complex challenges brought about by the global COVID-19 pandemic have had numerous impacts on the region. Given this scenario, out-of-the-box methods and innovative ideas need to be embraced. News articles covering Myanmar, encompassing noteworthy events at the borders of Manipur and Mizoram, the incident involving the crash of a Myanmar plane on the runway which plans to evacuate soldiers running away from their posts, and detailed discussions on the battles in northern Shan State have been described. Additionally, there are interviews with scholars and certain leaders from the opposition in Myanmar.

1At the SAC meeting 1/2024 held on February 1, 2024, Snr. Gen. Min Aung Hlaing stated that “the SAC’s primary purpose of providing political guidance to the nation. In line with this objective, council members were carefully chosen from Regions and States, ensuring the inclusion of capable individuals, including top authorities from the Myanmar Armed Forces (MAF) and leaders representing ethnic minorities.”

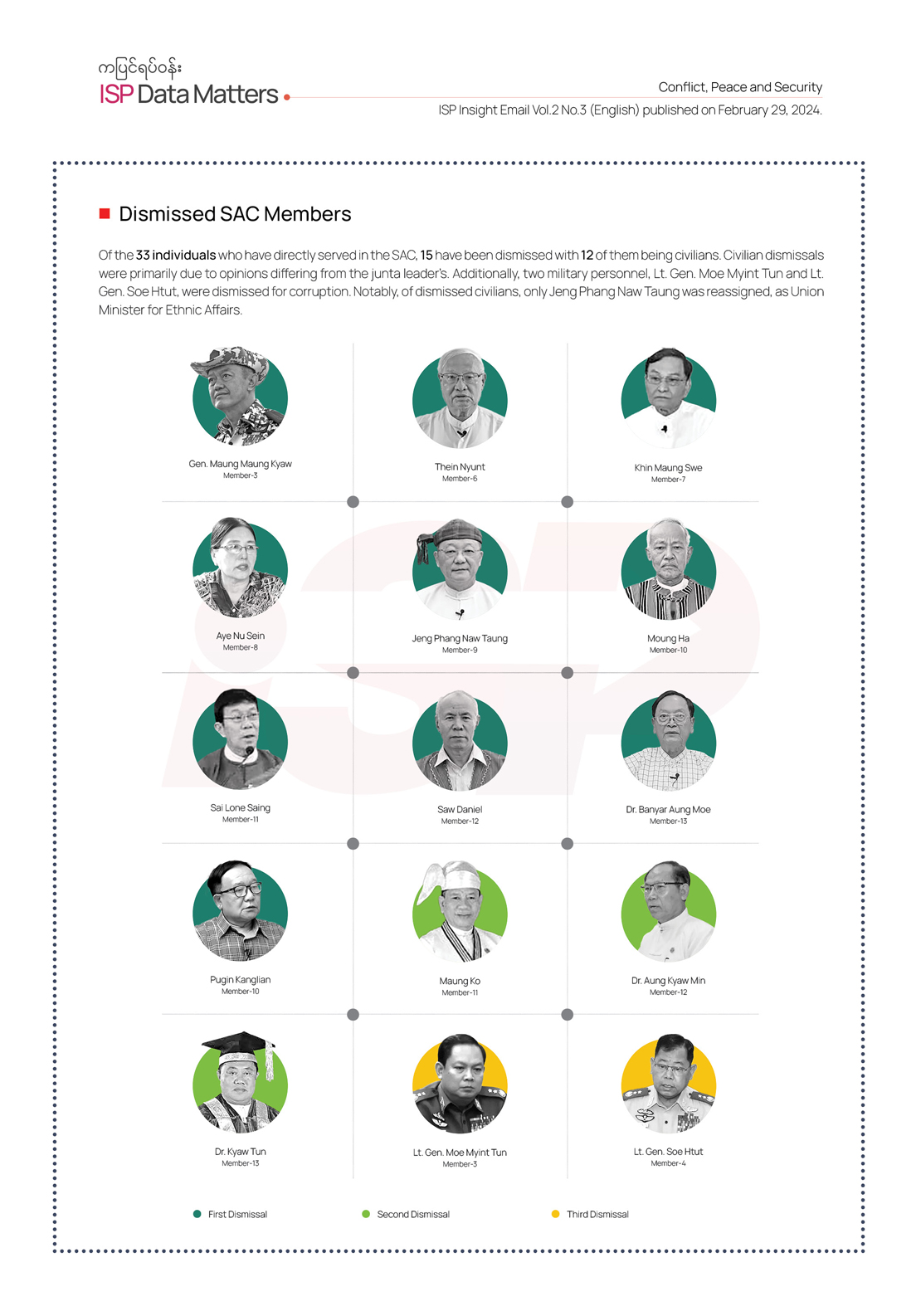

2 Within three years, three military members and 12 civilians were removed from the SAC. Gen. Maung Maung Kyaw, former Commander in Chief of the Air Force, was the first military official to be removed. The other two military officials, Lt. Gen. Moe Myint Tun (DSA-30), who is ranked 6th in the army, and Lt. Gen. Soe Htut (OTS-64), Minister of Home Affairs, were dismissed for using their position and authority to gain self-interest. From the civilian sector, Thein Nyunt, Khin Maung Swe, Aye Nu Sein, Jeng Phang Naw Taung, Moung Ha, Sai Lone Saing, Saw Daniel, Dr. Banyar Aung Moe, Maung Ko, Dr. Aung Kyaw Min, Dr. Kyaw Tun and Pugin Kanglian.

3 The law amending the Political Parties Registration Law enacted by the SAC on January 26, 2023, mandates that political parties operating nationwide must deposit 100 million Kyats (approximately 47,600 USD, using the SAC’s official exchange rate of 1 USD = 2,100 MMK) in a bank and establish party offices in at least half of all townships (over 165 townships) and have a minimum of 100,000 party members within 180 days of registration. These requirements pose a significant challenge for smaller parties. The law underwent amendments in January 2024, reducing the required number of members by half from 100,000 to 50,000. Additionally, the obligation to establish offices in half of the country’s townships was revised to one-third (110 townships).

To receive ISP Insight Emails in your inbox, subscribe at this link.