On Point No. 17

(This OnPoint No. 17 is published on November 13, 2023, as a translation of the original Burmese language version that ISP-Myanmar sent out to the ISP Gabyin members on November 10, 2023.)

∎ Events

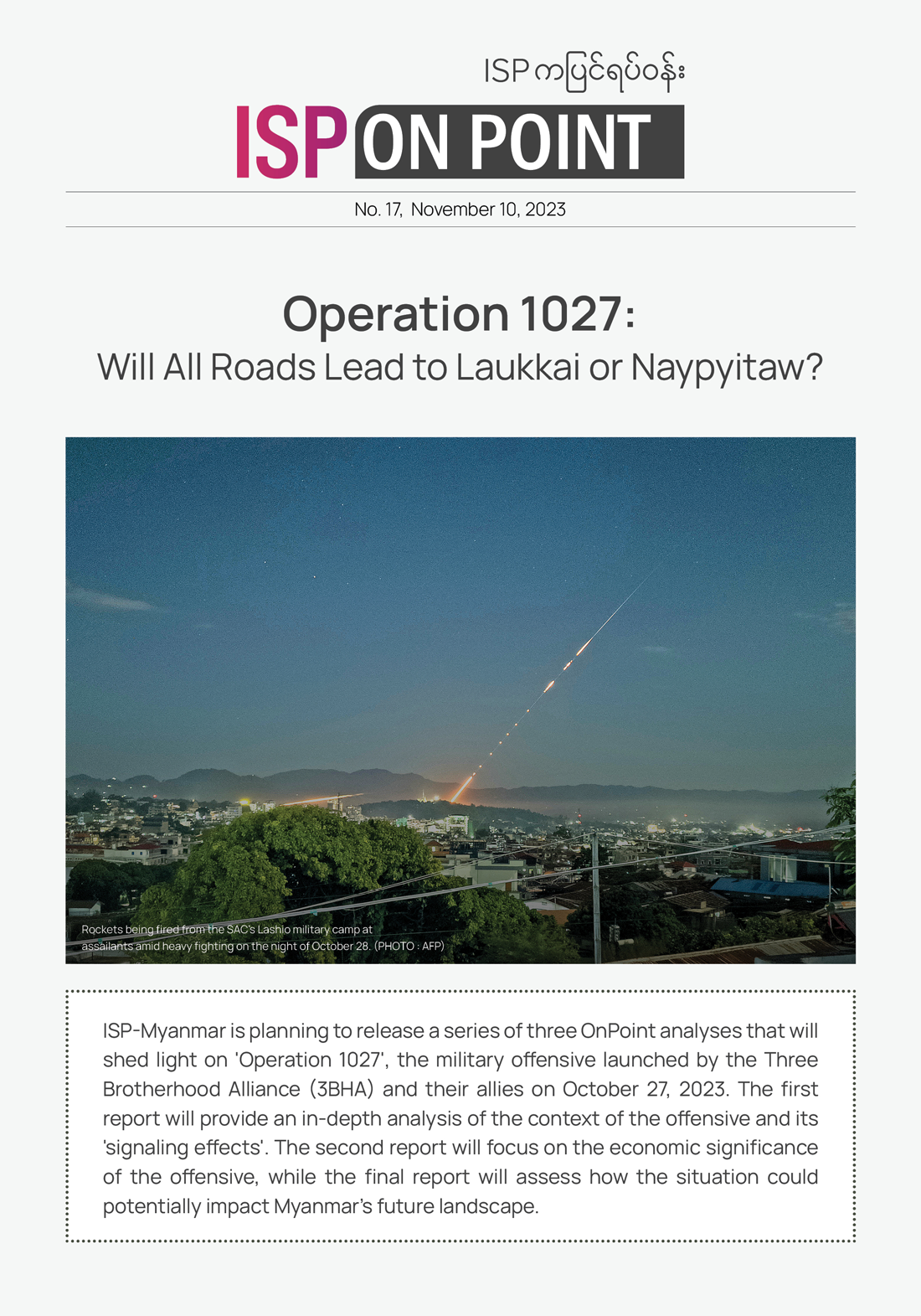

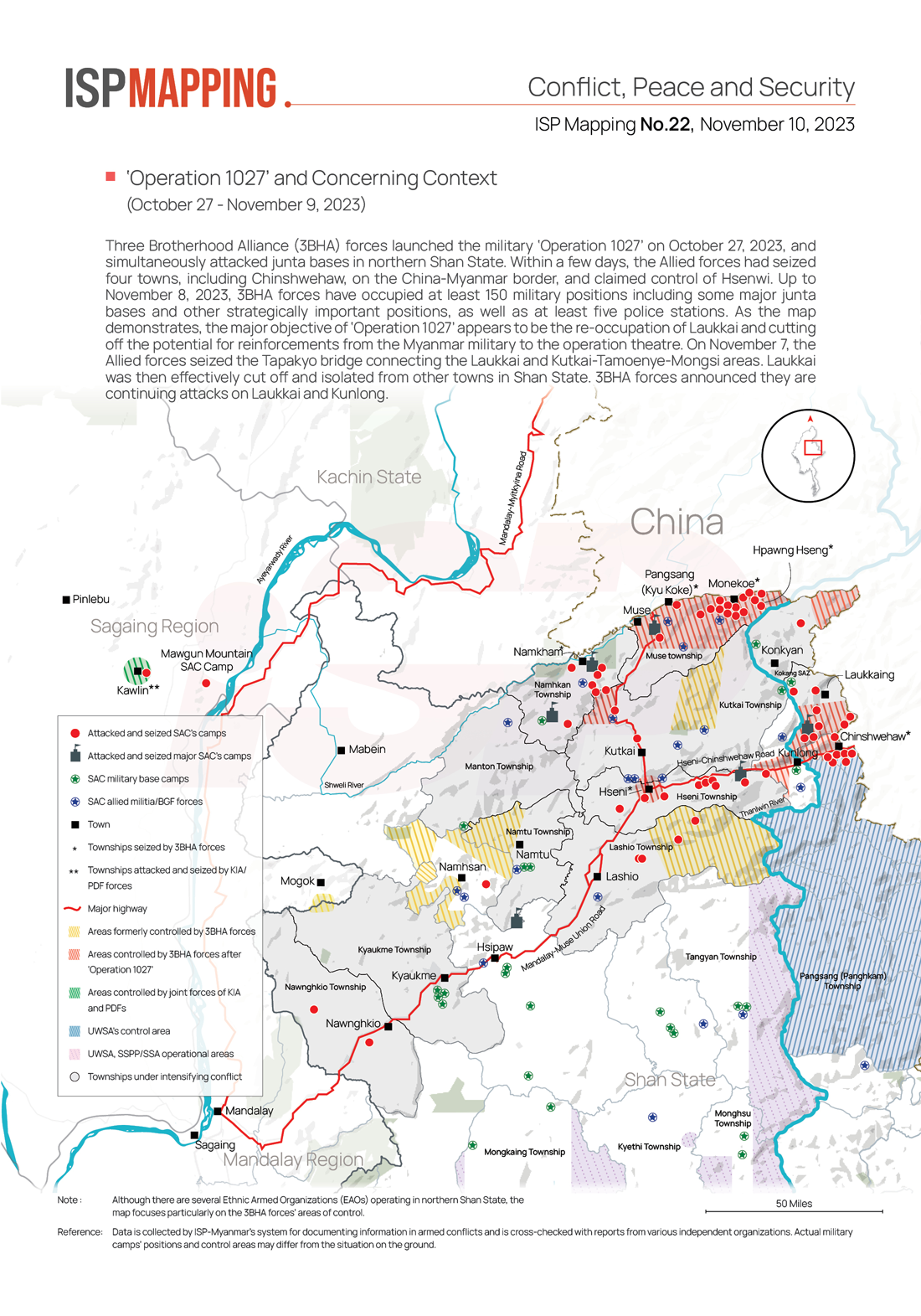

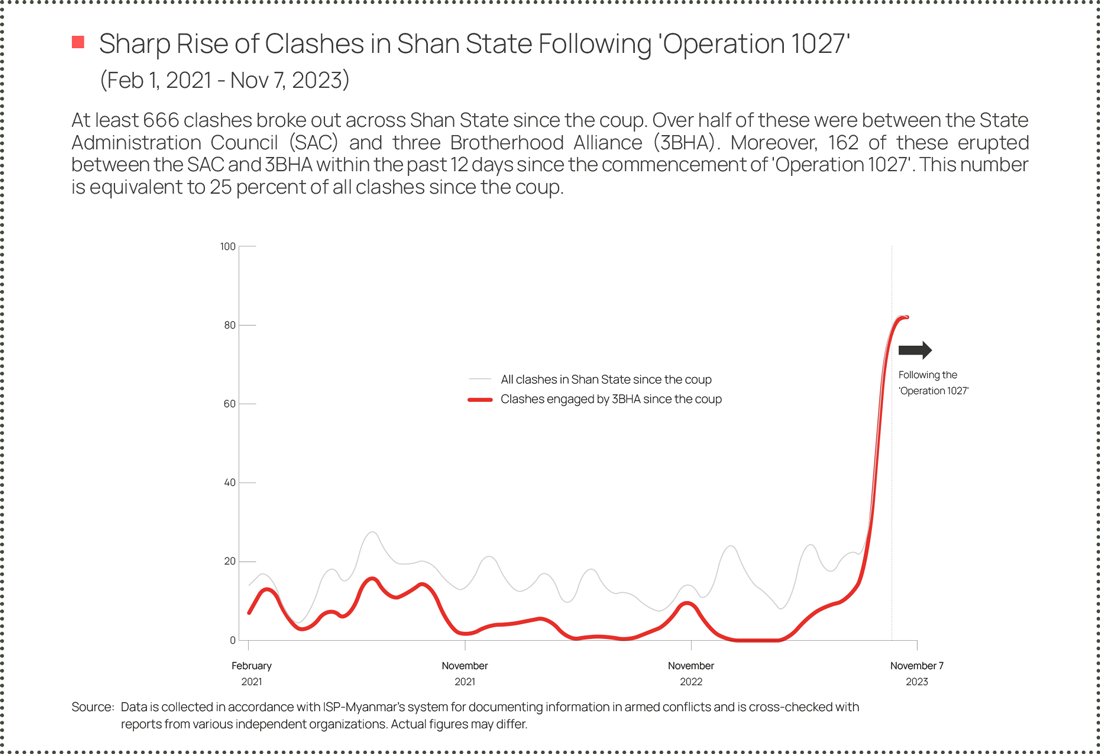

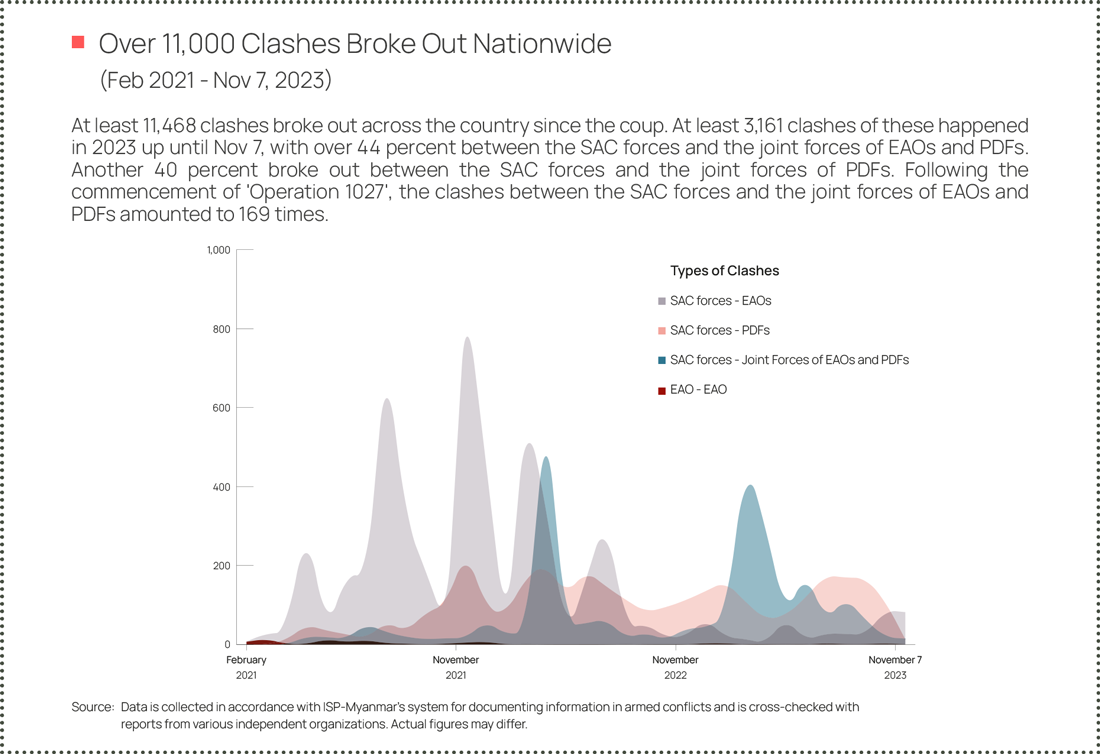

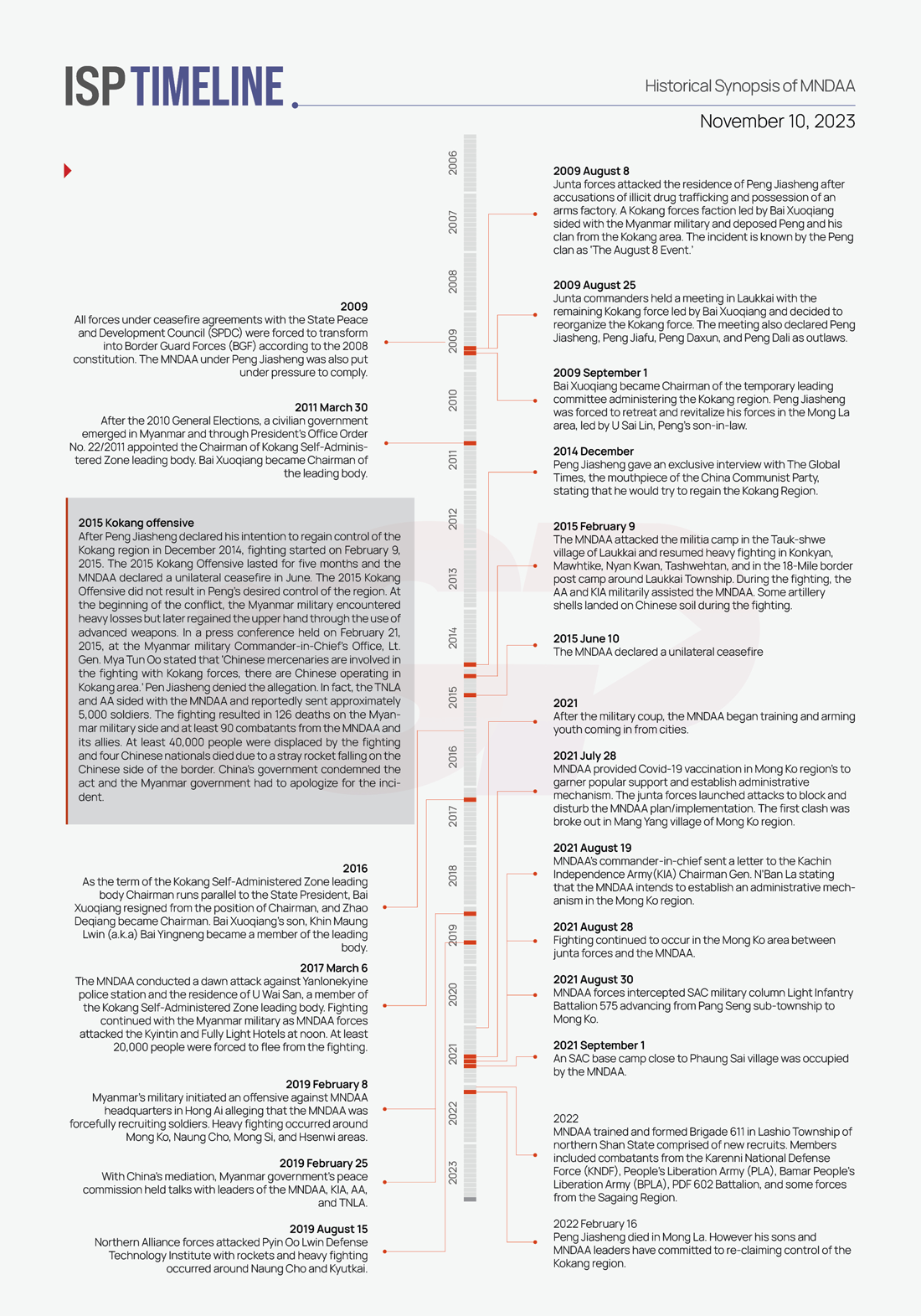

On October 27, 2023, the three Brotherhood Alliance (3BHA), namely the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), and the Arakan Army (AA), along with other allied forces launched the military ‘Operation 1027’1. Within a few days, the initial phase of the operation resulted in effective 3BHA control of five towns along the China-Myanmar border including the Chinshwehaw border checkpoint. By November 8, the 3BHA’s forces had seized more than 150 military camps including some strategic positions and base camps, along with at least five police stations. 3BHA and allied forces reportedly seized six tanks, four military trucks, two howitzers, and a large stock of ammunition and weapons from State Administration Council. Tatmadaw Infantry Battalion No 143 based in Kunlong surrendered to 3BHA and allied forces amidst heavy fighting. The resistance forces seized two important bridges and effectively cut off national highway access to the region. A 3BHA statement lists the military objectives of ‘Operation 1027’ as combatting widespread online fraud and gambling, asserting their right to self-defense, maintaining control over their territory, and ultimately eradicating oppressive junta military rule.

1 In ‘Operation 1027’, along with 3BHA forces, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) (Myanmar), Bamar People’s Liberation Army (BPLA), People’s Defence Force (Mandalay), and Moe Goke Tactical Command PDF forces are all collaborating with the 3BHA in the military operation.

∎ Preliminary Analysis

Recent conflict history in northern Shan State has shown that significant shifts often occur rapidly when China’s interests in Myanmar reach a pivotal point. Conflict actors in Myanmar, whether they are state or non-state actors vying for complete or partial power, can capitalize on this opportune moment by acting decisively. Essentially, the key is for Myanmar conflict actors to take action when China’s interest in Myanmar is at its peak.

To demonstrate, in 1988-89, when Kokang and Wa ethnic armed forces rebelled against the leadership of the Communist Party of Burma (CPB), Deng Xiaoping’s China, which had been recently successful with reforming towards a market-based economy system and experimental opening to international trade, reversing their previous patronage with the CPB leadership. The person who most effectively seized the moment of this watershed opportunity presented by China’s backflip was the intelligence chief of the former junta, State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), Brig. Gen. Khin Nyunt. At this critical juncture. Khin Nyunt made a groundbreaking proposition to the Kokang and Wa forces—an unprecedented move in Myanmar’s history. He made a proposal to the armed groups in northern Myanmar, that they be permitted to continue to hold their weapons but enter into ceasefire, collaborating with the junta for regional development, and that in return they would be permitted to engage in any business activities they liked to raise revenue, whether that be illicit drug trafficking or money laundering, they would be free from interference from the ruling junta. This new ceasefire initiative of the military intelligence developed into an institutionalized ‘ceasefire crony capitalism’ in the period that followed. This new attempt at a form of ceasefire changed the landscape of conflict not only in northern Myanmar but also across the whole nation.

The rapid growth of the Arakan Army (AA) can also be understood through this ‘China opportunity’ lens. After Myanmar’s 2010-11 political transition, the hybrid civilian government in September 2011 unexpectedly suspended billions of dollars worth of Chinese investment dam project at the Myitkyina site at the Ayeyarwaddy River confluence in Kachin State. More importantly, China’s concerns grew as U Thein Sein’s administration became more friendly with various Western governments. China had previously been pursuing deep strategic interests with Myanmar, particularly through the Kyauk Phyu deep-water seaport, which also included a Special Economic Zone (SEZ), as a form of Chinese access to the Indian Ocean, as well as China’s oil and gas pipeline which passes through Rakhine State to inland China’s Yunnan Province. China could probably foresee strategic opportunities northern Shan State and in Rakhine State, not only to expand its economic interests but also to expand its state reach in order to guarantee security to its projects. The conflict actor who took advantage of this situation was Gen. Twan Mrat Naing, chief of the Arakan Army (AA). When the AA was founded in 2009, its force numbered only 29 men, but after the event of suspension of the Myitsone Dam project in 2011, and after relocating their major forces into Rakhine State in 2014, the AA subsequently strengthened and its numbers swelled to several thousand troops. The AA has since become the second-largest ethnic armed organization (EAO) after the UWSA.

In analyzing ‘Operation 1027,’ the Kokang forces and their allies, and specifically the three Brotherhood Alliance, have effectively mobilized themselves and embarked upon a mission-centric objective which does align with China’s own concerns over the eradication of ‘Kyar Phyant’ (诈骗)– online fraud, and gambling. China’s rhetorical intolerance towards cyber-scams, which have victimised thousands of its citizens, is a driving force behind China’s agenda. Within Chinese society, the issue of online scams and slavery within illicit border-zone cartels gained prominence immediately after the release of the blockbuster film ‘No More Bets.’ Chinese citizens’ concerns and criticism created a hot issue for Chinese authorities. While Chinese officials have raised the issue seriously with the Myanmar junta many times, the junta has seemingly been either inattentive or has treated the problem lightly. Moreover, Chinese authorities have given time to Bai Xuoqiang of the Kokang Self-Administered Zone, however no results have materialized. Worse still, up to October 20, 2023, reportedly about 60 Chinese citizens have been killed in the Kokang area, including undercover Chinese police. Bai Xuoqiang has seemingly defied Chinese warnings, by emphasizing his association with the SAC Chief in political and business matters. This is tantamount to Bai challenging China’s attempts to impose pressure on the Kokang leader.

In terms of the Wa region, China is seemingly disgruntled with the rise of new generational leadership in the UWSP, as these new leaders seem more nationalistically inclined. China may feel that the new Wa leadership might become less open to listening to China’s perspectives and wishes in the region. This could be the main reason behind why Chinese authorities themselves have become involved in extra-territorial arrests of Kokang, and some Wa, leaders, and issuing warrants against those who are alleged to have committed criminal activities under Chinese law. These arrests aimed to shake up Wa’s leadership under the claim of their involvement in the Kyar Phyant online gambling industry. China appears to selectively target only Kokang and Wa leaders, while appearing satisfied with Mong La leaders, suggesting reliance on Mong La. In a broader perspective, while Kyar Phyant is now an immediate issue in northern Myanmar, the longer-term horizon, raises a hypothesized scenario in which China is actively engaged in reconfiguring its power projection capabilities in the area. The immediate focus on Kyar Phyant could be a strategy to address multiple concerns simultaneously. To comprehend the interplay between China’s short-term and long-term strategies in northern Myanmar, attention must be directed not only to security matters but also to the intertwining economic interests of China in the region. (The upcoming ISP-Myanmar OnPoint No. 18 will discuss these economic linkages).

A more thorough analysis of the assumption of China’s role in internal power reconfigurations in northern Shan State could consider the following scenarios and projections: 1) China may intend to replace the present Kokang leader Bai Xuoqiang with new leadership; 2) China may send a ‘Do and Do Not’ message to the UWSA leadership, using the immediate issue of Kyar Phyant online gambling against the background context of rising Wa nationalism; and finally, 3) China could strengthen its interests east of the Salween River, by reinforcing demographic (ethnic population ratios) and economic power. In conclusion, the ongoing ‘Operation 1027’ in Kokang is a convergence of China’s interests and the MNDAA’s goal of reclaiming control over Laukkai. The strategic aim of the operation may involve reoccupying Laukkai as a base, while the stated objective of ‘eradicating the oppressive military rule in Myanmar’ could serve as a tactical agenda—a shrewd preemptive measure to garner popular support.

China may provide a ‘green light’ to ‘Operation 1027’, but it should be noted that conflict actors in Myanmar are not so passive or subjective as to act on signals from China. Myanmar actors have consistently demonstrated their own agency, and that they can reinvent their positions within the given situation to maximize their strategic options, from the strategic management of Khin Nyunt in 1989, to the strategic-sophisticated Twan Mrat Naing of the AA after 2011, to the recent military maneuvers of the 3BHA. History has demonstrated that these forces have the ability to seize opportunities, remold their positions to achieve more favorable conditions and that they are more than capable of producing results on their own terms.

While conflicts as part of the current ‘Operation 1027’ have been raging broadly in at least eleven townships, the main target of the operation remains the re-occupation of Laukkai, while other battles’ objectives are to cut off supplies and reinforcements to the Myanmar military (Please see ISP Mapping No. 22).

∎ Scenario Forecast

How can we initially assess whether ‘Operation 1027’ will expand its scope in terms of objectives, tactics, and ambition? Could the offensive ultimately lead all the way to Naypyitaw, as the opposition National Unity Government (NUG) has claimed? To engage with these aspects and more, we should analyze the ‘signaling effects’ of the ongoing operation.

Firstly, what signal is the ‘Operation 1027’ offensive sending to the Myanmar military? The success of the operation demonstrates Myanmar’s military weakness and loss of popular support in northern Shan State. The Tatmadaw may be materially superior to the resistance forces, but is facing intelligence and security failure at the same time losing the will to fight. ‘Operation 1027’ also signals that top Tatmadaw leadership lacks suitable withdrawal options for regular troops caught up in this crisis. Considering external pressures, ‘Operation 1027’ calls into question whether the junta military might face internal implosion depending on whether the theatre of war can expand beyond northern Shan State.

Secondly, 3BHA’s ‘Operation 1027’ offensive sends strong signals to other armed resistance groups on the capabilities of the junta’s state power. These other resistance forces can then make their own assessments on whether the Tatmadaw is in a vulnerable position or not, and whether they can risk entering into an all-out war or not. These third-party armed resistance forces can for now stay uninvolved in the conflict while assessing the cost-effectiveness of joining the fray. It can already be observed that other armed resistance groups in Sagaing Region, including the KIA, NUG’s PDFs, and local defense forces (LDF) have already begun launching simultaneous attacks, and that resistance groups from Karenni are also coordinating attacks under the codename ‘Operation 1107.’ However the Arakan Army (AA), one of the three constituent 3BHA forces, is still holding to an informal ceasefire in its home Rakhine State and is reluctant to join the all-out fight.2 Future expansion of the war theatre thus depends upon the internal calculations of the larger EAOs.

2 Editor’s note: Since the publication of this OnPoint No. 17 Burmese version, Arakan Army (AA) initiated offensive attacks against SAC forces in many townships of Rakhine State on Nov 13, 2023.

Thirdly, the 3BHA offensive also sends signals to fellow EAOs to observe each other’s actions cautiously. While many young Bamar are eager to fight and dedicated to ending the military dictatorship, many EAOs have been considering their own historical experiences of territorial disputes based on ethnic demographics, frictions between forces emerging as external actors expand into their area, and historical distrust of one another. If an EAO force expands into a disputed land in the name of resistance and hoists a popular flag, the response of other EAOs will become an interesting question. The internal limitations of each EAO will contribute to their decisions on whether to expand the theatre of war.

Fourthly, as the offensive progresses, it will send a signal to city dwellers on whether they could expect to encounter war and whether to prepare for insurrection or not. Some existing underground units in cities are capable of igniting conflicts within cities, and/or civilians in the general population could mobilize themselves to raise an insurrection. It is hard to speculate on details of such a scenario, but the possibility of the existing war theatre expanding brings into play the possibility of city insurrections against the junta.

Finally, this offensive sends signals to neighboring countries, including China. Conversely, if a non-neighboring country, such as the U.S. or Russia, were to become perceivably involved in the conflict in some form, the war theatre could expand internationally and become more complicated through geopolitical involvement. It seems obvious that the 3BHA forces are determined to take back Laukkai before February 2024, the anniversary of Kokang leader Peng’s death. Questions will arise about whether the Myanmar military, perhaps with Chinese mediation, could accept the initial losses from ‘Operation 1027’ or opt to risk taking higher losses by extending the conflict through launching counter-offensives against 3BHA forces. Roads marked by the smoke and scent of war will converge on at least Laukkai and maybe even Naypyitaw, their trajectory influenced by the ‘signaling effects’ of ‘Operation 1027.’ Whatever the next stage of operations, the unfolding scenario warrants thorough and continuous investigation.

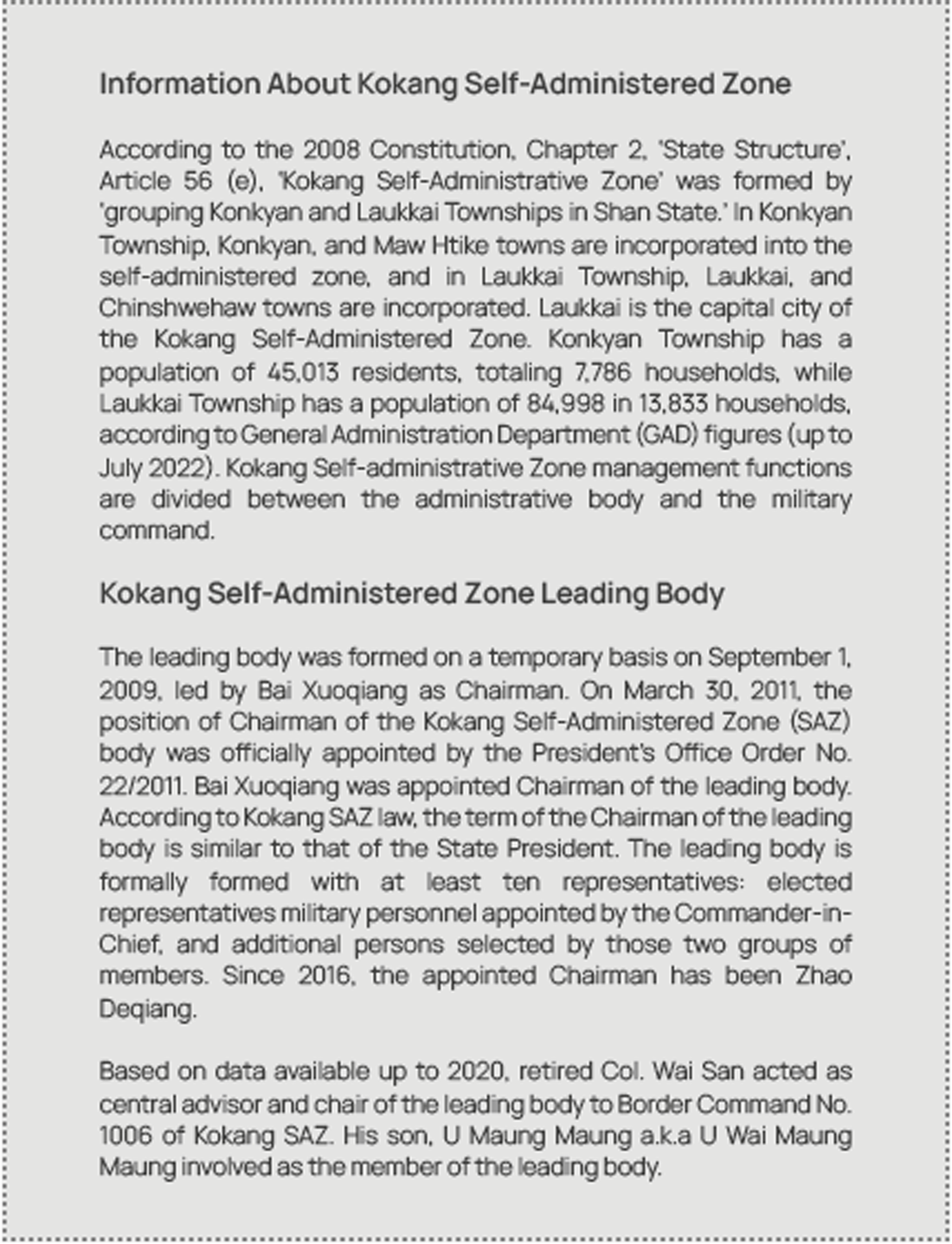

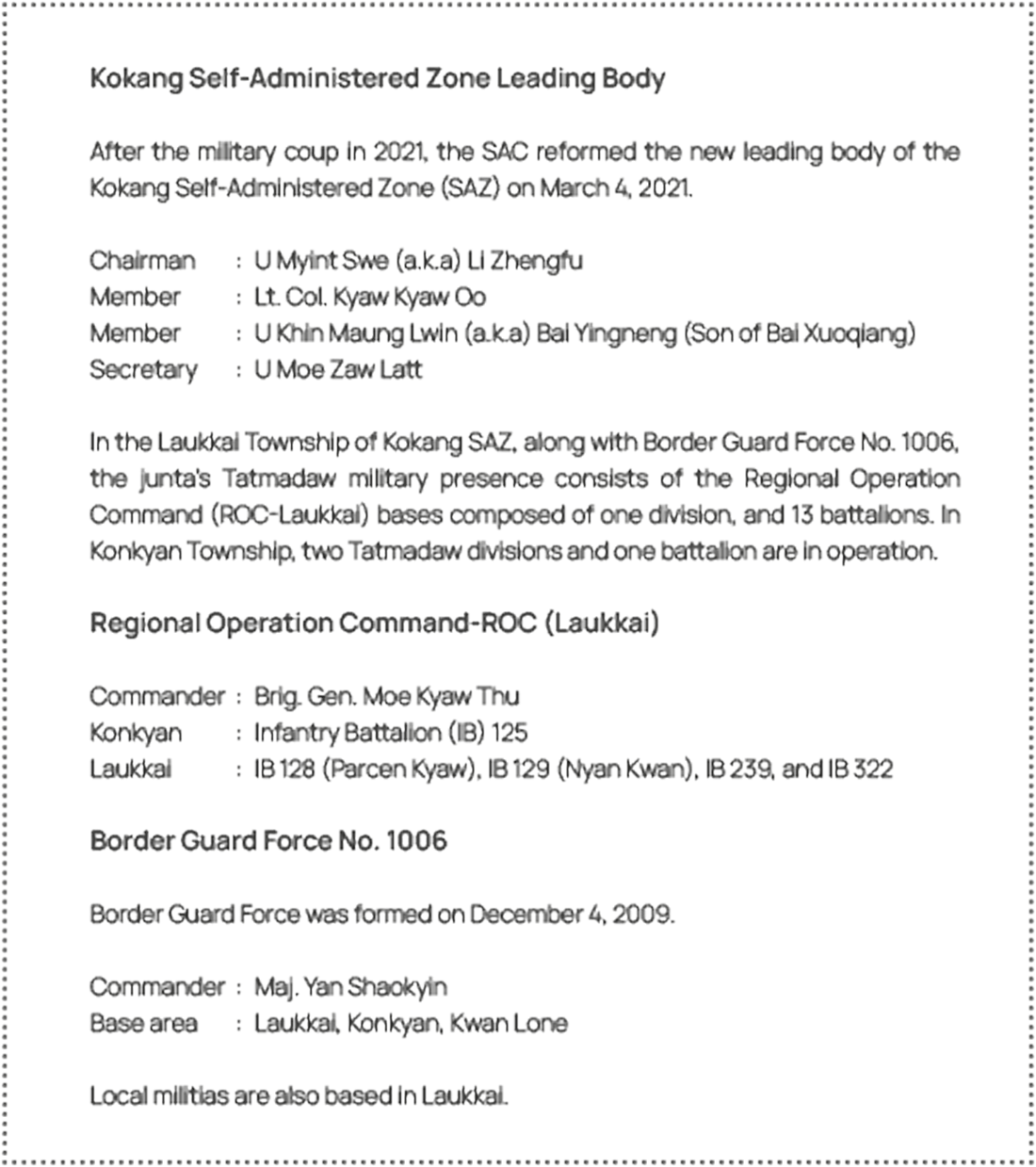

For background information on the Kokang Self-Administered Zone (SAZ), covering topics such as Kokang’s inclusion into Myanmar territory, the Peng family, Yang family, Pe family, and the Kokang army in the past, as well as the modern-era MNDAA (Myanmar Democratic Alliance Army), please visit the ISP Gabyin Community.