On Point No. 19

(This ISP OnPoint No. 19 is published on December 12, 2023, as a translation of the original Burmese language version that ISP-Myanmar sent out to the ISP Gabyin members on December 5, 2023.)

∎ Events

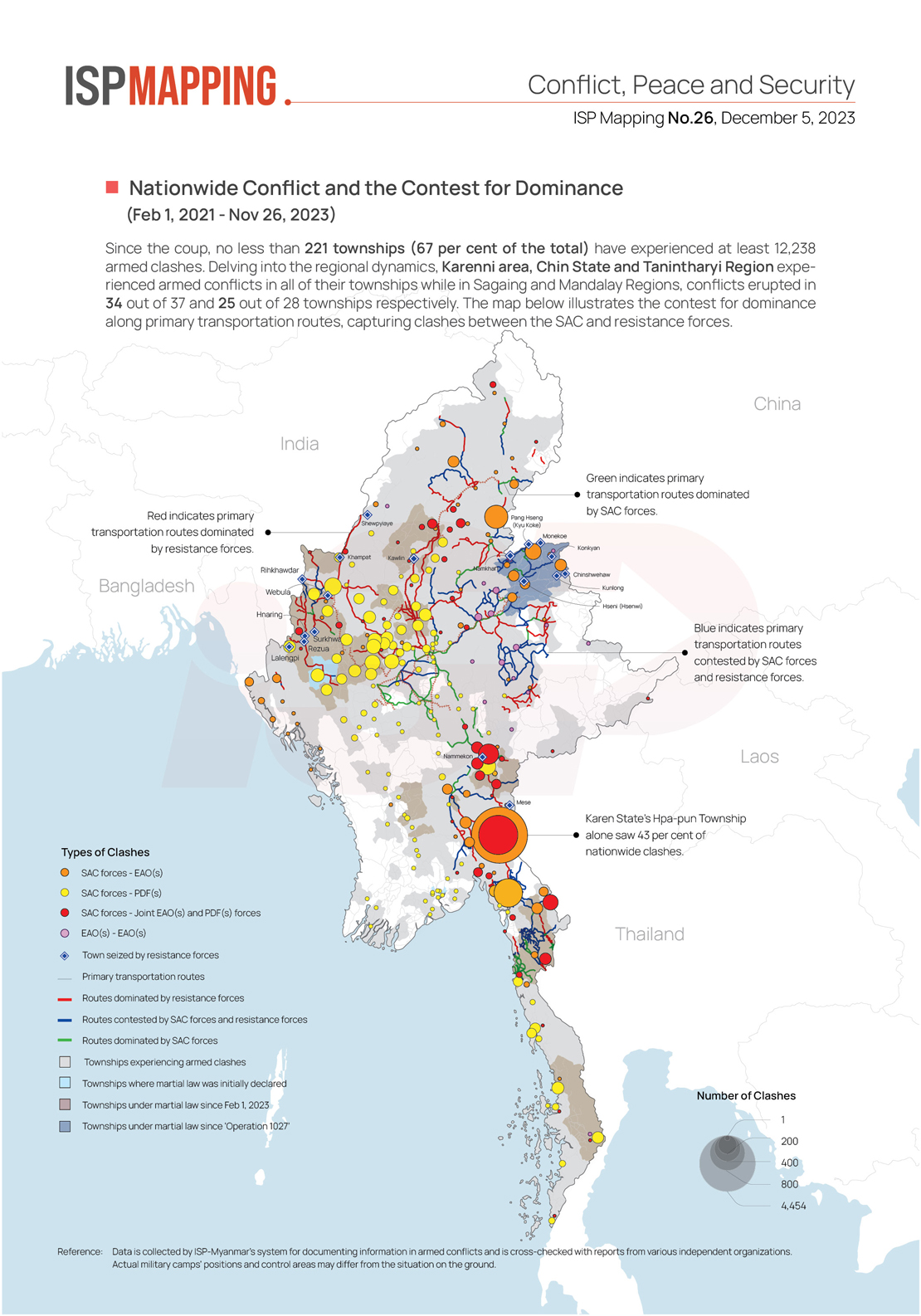

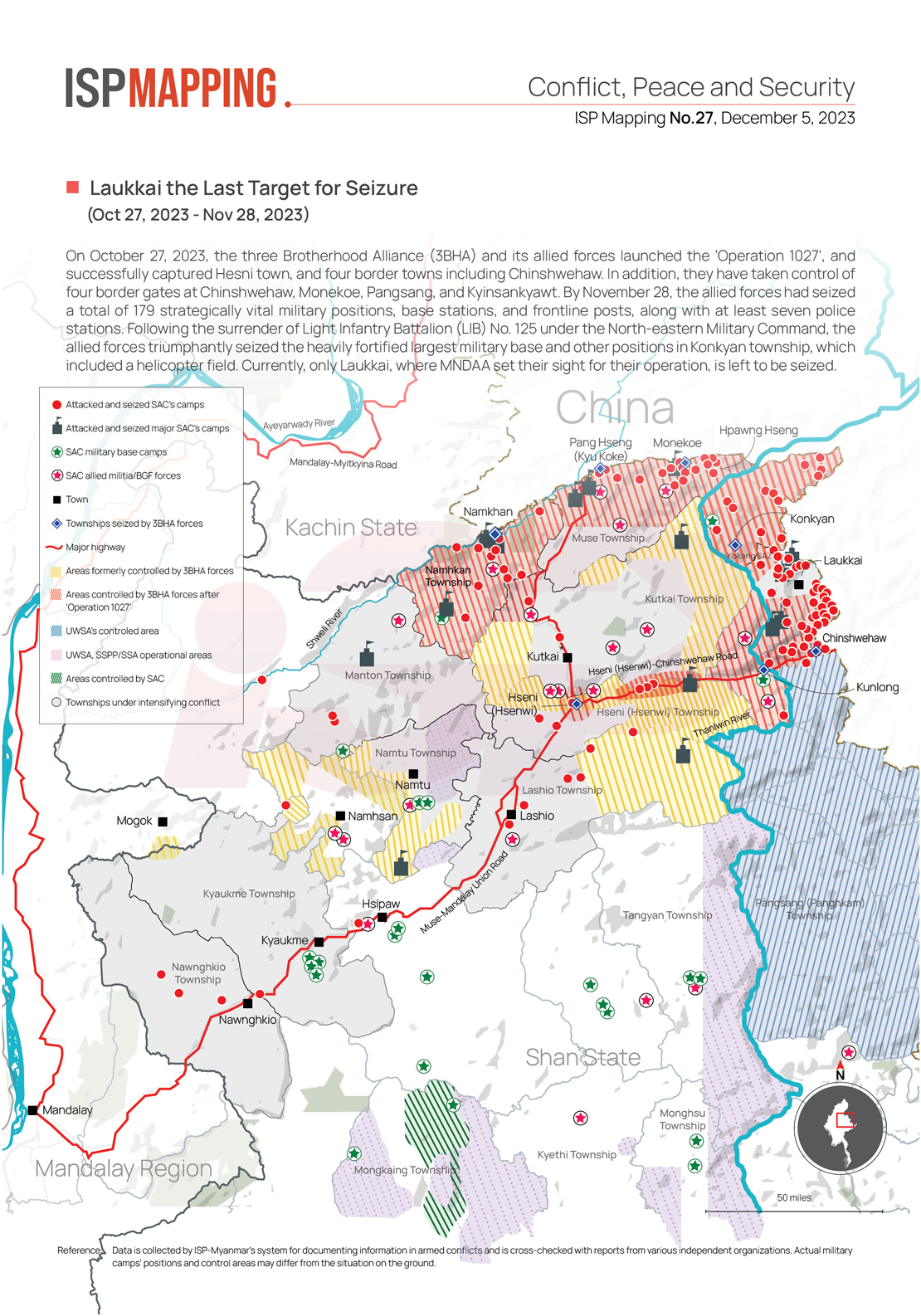

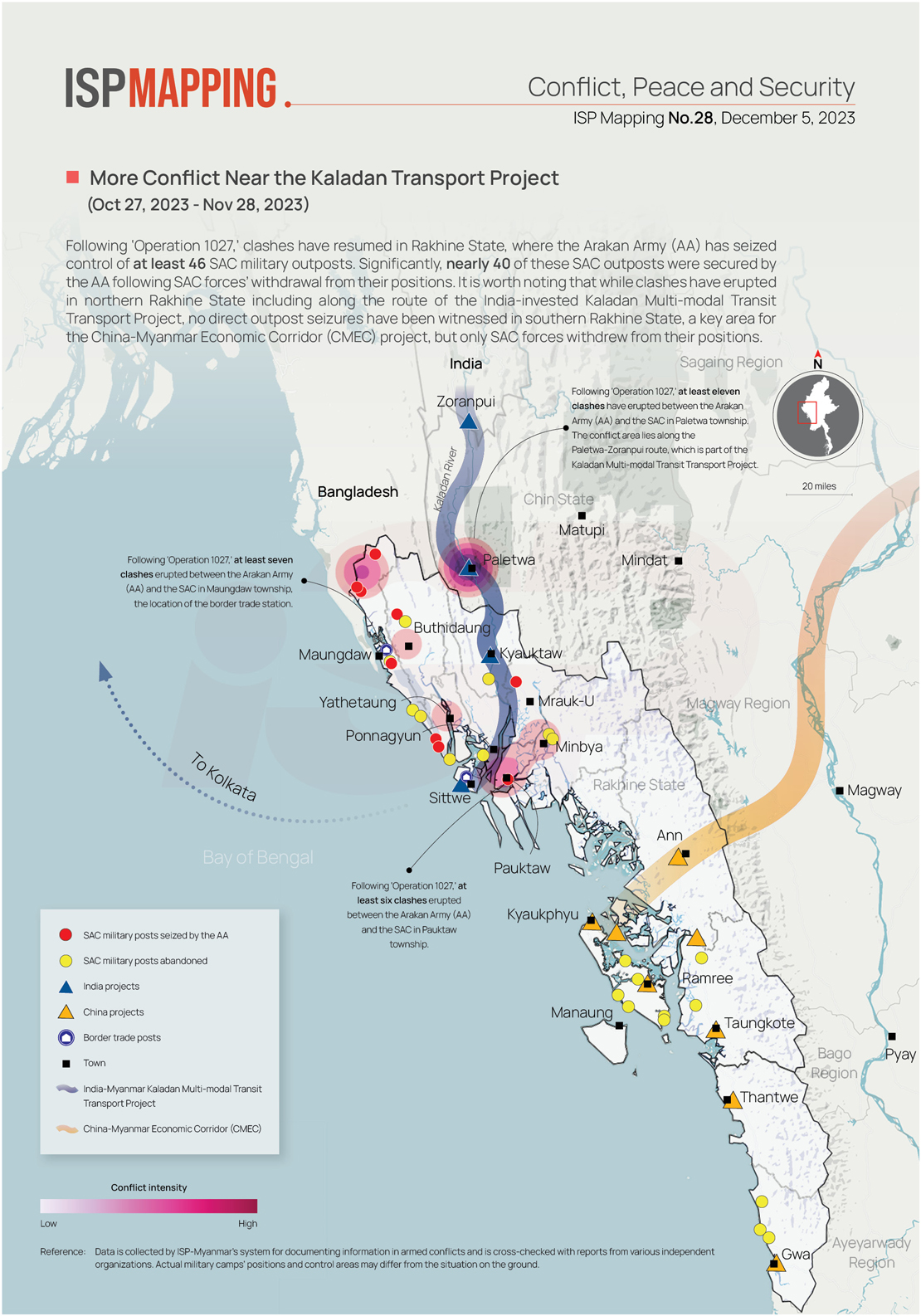

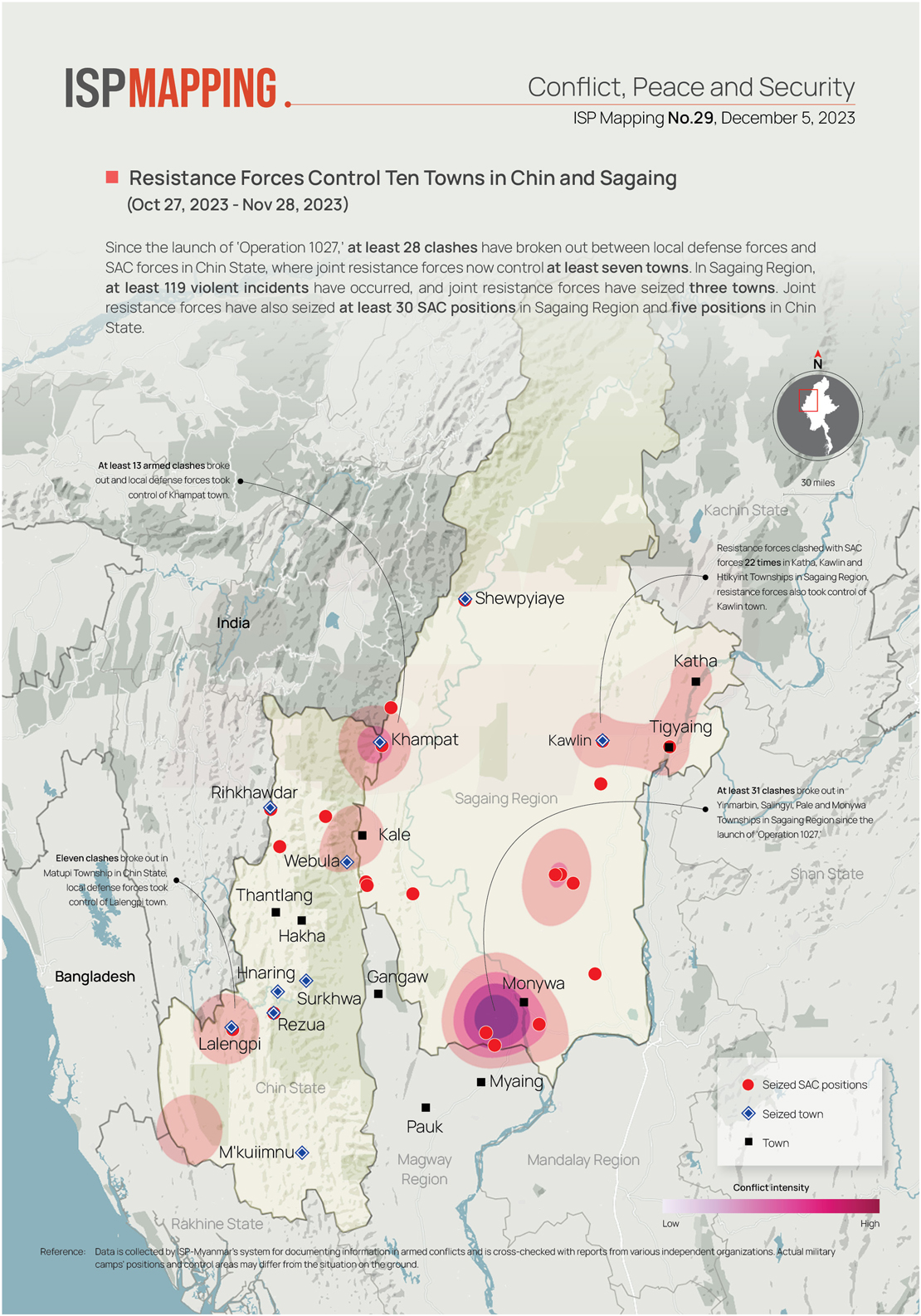

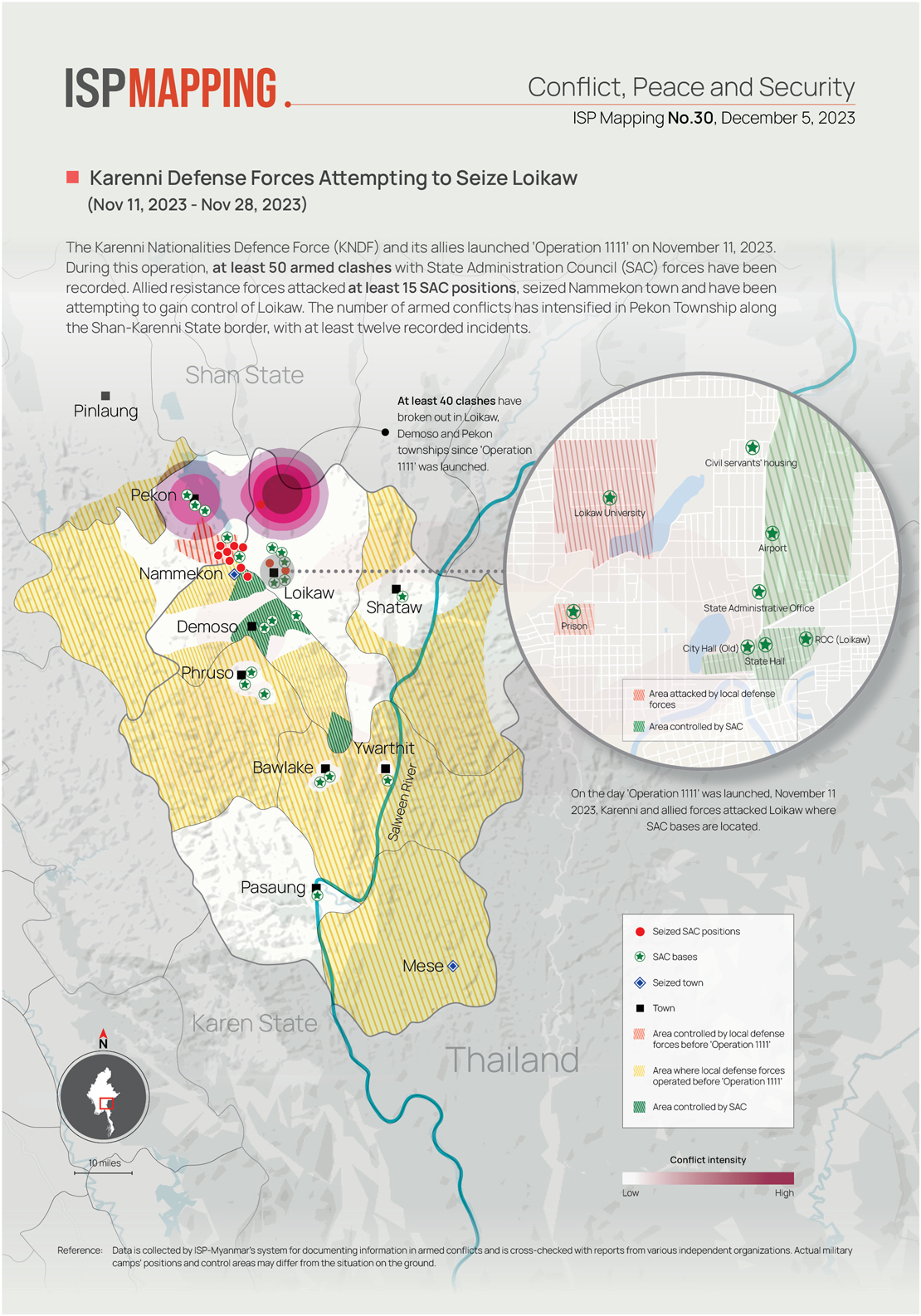

On October 27, 2023, the Three Brotherhood Alliance (3BHA) launched ‘Operation 1027’, and since November 14, 2023 have called for a nationwide mobilization to revolt against the military dictatorship. In the Karenni area, resistance groups have extended the war front to Loikaw, the state capital. Similarly, in Rakhine State, the Arakan Army (AA) has attempted to take control over strategic positions in border trade and major economic projects. In Karen State and Chin State, and in the Myanmar dry zone including upper Sagaing, resistance groups have flexed their muscles in renewed offensives. Acting President of the State Administration Council (SAC), Myint Swe evaluated the situation in the recent National Defence and Security Council (NDSC) meeting on November 8, by saying “if the government does not effectively manage the incidents happening in the border region, the country will be split into parts.”

Note: Since the publication of this OnPoint No.19 Burmese language version, new development has occurred.

With China’s “support and facilitation”, representatives of the State Administration Council (SAC)engaged in “peace talks” with three ethnic armed groups who were involved in an ongoing ‘Operation 1027’ in Kunming, China, on December 11. The junta’s spokesperson confirmed the news. China foreign ministry official said the peace talks had yielded “positive results”.

∎ Preliminary Analysis

‘Operation 1027’ has escalated the conflict in Myanmar to a new level. Since the post-coup Spring Revolution, the prospect of a political resolution restoring the pre-coup ‘old normal’ is no longer feasible. ‘Operation 1027’ has further entangled Myanmar’s conflict landscape with geopolitics, pushing the extant political power configuration and territorial integrity of the Myanmar polity beyond a mere status quo and into an irreversible trajectory. This shift is not contingent on Myanmar’s national democratic legitimacy or adherence to a federal framework. Rather, it indicates a declining ability of the state to function effectively. The state has lost control over its ability to maintain law and order, collect taxes from a struggling economy, enter into contracts with foreign governments regarding sovereign affairs, and deliver essential public services such as water, electricity and healthcare. As the state loses control over the territory, it loses the ability to exercise power effectively in terms of functional and territorial reach.

Humanitarian crises continue to worsen with no foreseeable international assistance to tackle them adequately in the near future. Youth resistance fighters have taken the opportunity of the crises facing the SAC to escalate “tipping-point armed revolution” under the slogan ‘wave after wave,’ referring to recurring and ongoing resistance movements. Their determination to secure victory has intensified. Whether or not these movements could lead to ‘total war’, which could remove the junta regime, is the key focus of ISP OnPoint No. 17, which has particularly highlighted the ‘signaling effects’ of the military operation and how this could be interpreted by Myanmar’s military officers, ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), and neighboring countries, including China, and further afield in some of the Western powers. Conflict stakeholders in Myanmar, such as EAOs, their supporters, and local and international allies, will calculate the direction of the winds of conflict and the strength of the conflict’s momentum to estimate how far the current movement will progress. Based on these calculations, their subsequent decisions on their involvement levels will shape the current movement’s course.

The immediate consequences of ‘Operation 1027’ demonstrate significant shortcomings in Myanmar military’s (SAC) preparedness, intelligence, battle readiness, morale, and popular support. The military finds itself overstretched across multiple fronts, rendering it fragile and vulnerable. Based on ISP-Myanmar’s findings, in the aftermath of ‘Operation 1027,’ at least eight SAC Regional Military Commands (RMC), at least four Regional Operations Commands (ROC), at least ten Light Infantry Divisions (LID) and at least nine Military Operations Commands (MOC) have been deployed to front line fighting to engage with various resistance forces groups and EAOs across 67 per cent of the country’s total area. SAC forces have now been spread so thin to the extent that additional support can no longer be supplied to these front line forces. SAC forces seem to be cornered in every direction. In addition, at least 20,000 to 25,000 security forces must be constantly held in reserve to respond to potential urban anti-junta demonstrations and the wider anti-junta movement. To this end, the SAC needs to maintain at least 15 to 20 battalions surrounding each major city, such as Naypyitaw and Yangon.

A standard infantry battalion structure typically consists of about 55-60 officers and around 650 soldiers, resulting in a total troop size of roughly 700. However, in reality, some battalions are formed with only around 300 soldiers, while many others are formed with just 230-250 soldiers. Worse still, most battalions are formed with fewer than 170 soldiers. When infantry battalions have only around 170 soldiers, approximately 35-40 are required to remain at the base camp, meaning that the operational forces available to go to the frontline are only around 130 soldiers per battalion. The accurate number of operational combatants in a given battalion could be further reduced due to soldiers being absent due to poor health, desertion, or arrest and imprisonment. Therefore, if a battalion can send even 110 combatants to the frontline, it can be considered a strong unit.

During ‘Operation 1027,’ Infantry Battalion No. 129 under the Laukkai Regional Operations Command (ROC) in Kokang area, based in Yan Khaunt village in Laukkai Township, Kokang Self-Administered Zone, surrendered to the resistance forces’ assault. News reports recorded that at the time, there were only 126 combatants in the battalion’s base and a total of 262 people, including combatants’ family members. Similarly, when Light Infantry Battalion (LIB) No. 125 surrendered in Kone Gyan, only 93 combatants were present. Considering the case of Infantry Battalion No. 129, if the number of soldiers who either died in action, deserted, or were arrested for wrongdoings are presumed not to be listed, and assuming the number of these people to be around 40-50, then the total formation of the battalion could only be at maximum 170. Of these, we can assume 30 to 40 per cent of soldiers are made up of people in the age range of 40 to 50 or even older, making the actual number of effective soldiers closer to around a hundred.

The SAC fighting forces lie in stark contrast with the resistance forces. The majority of combatants from the Burma People’s Liberation Army (BPLA), People’s Liberation Army (PLA), People’s Defense Force (Mandalay), and Mogoke Tactical Command (PDF), who are fighting alongside 3BHA forces in ‘Operation 1027,’ are in the 20 to 30 year age range with high levels of aggression and battle readiness. In comparing numbers, a battalion of the People’s Defence Force (PDF) under the command of the National Unity Government (NUG) is reportedly formed with around 200 soldiers. In addition, the junta military units have not been able to expand their reach after the coup. Instead, they have been forced to remain in their limited operation zones due to security challenges, which has left them unable to secure the necessary resources and sustenance.

Actually, the Myanmar military has been struggling to care for its personnel, allocating a significant portion of defense expenditures to heavy artillery and defense systems, which are not directly relevant to fighting a civil war within the country’s own territory. The increased procurement of weapons is a lucrative business for corrupt high-ranking military officials and has also proved profitable for arms dealers. On the other hand, ordinary soldiers seem abandoned and underfed. Recent images of junta soldiers captured in the resistance operation demonstrated them as feeble, undernourished, and seemingly in ill health. Many soldiers had been assigned to the frontlines for prolonged periods since before the 2021 coup. Some had been deployed to frontline fighting in the Kachin and Rakhine areas for five to seven years without leave or the ability to visit their families. This protracted operational deployment period has made them socially weak. In the two and a half years since the coup, military assignment for a soldier in a frontline base has become similar to serving prison-sentence since they cannot go out and meet people because of the population’s antagonism towards them and other security risks as multiple armed forces are waging attrition war against them. Moreover, seeing injured fellow soldiers on the frontlines receiving neither support nor rescue must surely be a frightening experience for the combatants, weakening their morale. The consequences of this lead to distrust of their commanding officers, thus deteriorating the effective command and control within units.

As the military lacks popular support, the junta forces fail to receive intelligence information and even their own information is leaked to the resistance. Moreover, it is apparent that the junta military has failed to keep up with technological advances. In ‘Operation 1027,’ the resistance forces have deployed a battle tactic of attacking with multiple synchronized drones and drone-delivered explosives. Against such drone attacks, the junta units either cannot effectively use their jamming systems to defend themselves or else the 3BHA forces can bypass the junta’s jamming systems. 3BHA forces have effectively deployed a shower of drone-delivered explosives, which have proven effective against the junta forces. In one example, the Division Commander of Light Infantry Division No. 99 was killed when drone-delivered explosives collapsed his bunker. The junta forces’ unpreparedness in the face of this new tactic left many soldiers no alternative but to surrender to their assailants. The junta military is currently facing a critical period, compelled to reassess and modify its strategy, tactics, defense mechanisms, and responses to counter the EAOs’ offensive. This requires a complete rethink of how to manage its forces in the military theatre. Essentially, the junta military is now confronting some of the most daunting operational challenges in its history. In essence, the short-term crises that the junta military have faced under ‘Operation 1027’ have clutched away the veil which had covered the military’s competence. In the medium term, the SAC is muddling its way into a series of crises without being capable of finding a political exit.

Through careful analysis of the past, it can be observed that the Myanmar military has often attempted to handle crises by employing a dual-track strategy. This strategy involves using violent means to suppress opposition while pursuing a political offensive pathway against them. If the junta fails to strike a balance between these two tracks, it cannot defeat its opposition while also maintaining a viable political exit strategy. By “pursuing a political offensive pathway,” we refer to a political strategy or plan that, regardless of whether the opposition or international community endorses it, eventually forces or co-opts the opposition and the international community by dividing or weakening them.

For example, after the brutal crackdown against the 1988 democracy uprising, the junta allowed opposition political parties to register and paved the way for a new general election in 1990. Again, after the 2003 attacks against Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s convoy in Depayin, the former junta fashioned a ‘new political roadmap’ in 2004, and similarly, after the suppression of the 2007 Saffron Revolution (the monk movement), the former junta enacted the 2008 State Constitution. However, unlike in the past, until now, the current junta has only deployed heavy-handed actions against first the 2021 Spring Revolution and now ‘Operation 1027.’ The junta, this time, has barely come up with any viable political paths to accommodate and divide the opposition. For worse, the SAC has also made the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) impotent.

It is highly unlikely that the proposed elections by the SAC will take place due to the significant security risks and logistical challenges. Moreover, the election process does not meet the minimum requirements of a free and fair election, and the SAC’s election commission has made it difficult for parties to register. The general public is resentful about the recent violent crackdown and is unlikely to accept an election as a viable political solution. The main challenge for the SAC is whether to extend its term beyond January 31st, 2024, which marks the end of the junta’s three-year rule. Even if the military were to disband the SAC and set up a new body to oversee elections (by making some concessions such as releasing the imprisoned opposition leader, Aung San Suu Kyi), this would still fall short of addressing public grievances. In the medium term, any military defeat could lead the junta to restructure the balance of power among its top leadership or adjust its proposed roadmap. None of these questions can be ruled out for now.

Regarding the 3BHA’s ‘Operation 1027,’ in the short-term, the allied resistance group has pursued a limited military operation to reclaim Laukkai of the Kokang Self-Administered Zone as well as a general expansion of their areas of control. The 3BHA has also encouraged the entire country to mobilize to revolt against the junta’s military rule, which can be viewed as a tactical move in order to push the junta military forces to engage across multiple fronts and to reduce the ability to concentrate troops for any counter-offensive. However, this cannot be interpreted as engaging in a full-scale civil war with the objective of pushing for a complete victory against the junta.

One development worth observing is whether the weaponry and ammunition seized by the 3BHA since the beginning of ‘Operation 1027’ could be used to assault not only Laukkai and Hesni but also the junta’s North-eastern Military Command based in Lashio. Among the seized weaponry, the most destructive artillery pieces include the Israeli-made Soltam Systems M-71 155mm howitzer, the Soviet-made 122mm howitzer D-30 (GRAU index 2A18), Swedish-made Carl Gustaf 84mm recoilless rifles and US-made 75mm recoilless rifles. Similarly, captured 60mm, 81mm, and 120mm motor shells can be redeployed as drone-delivered explosives. 122mm and 105/130mm howitzers have a capacity for long-distance reach. According to reported photos, 3BHA forces have seized around 30 M20 75mm and Browning .50 calibre BMG machine guns, which are well-suited for use against Mi 17/35 attack helicopters. Notably, the resistance forces have also seized many anti-tank weapons, such as 81 mm mortars that are manufactured by the Myanmar military, as well as thousands of shells of ammunition.

Even if the war does not extend to a total war to remove the junta from power, ‘Operation 1027’ could still tip the balance of power in favor of the Northern Alliance in the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee (FPNCC). 3BHA forces have now come to presume that they can enjoy an equal military footing, at least with the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), and ‘Operation 1027’ will continue to weaken the control of other Shan EAOs over territory, power, and economic influence. This could lead to the expansion of the control area of 3BHA, increase their revenues by administering tax collection from border trade, and give them greater political influence, like princelings, at the expense of more seasoned EAOs in Kachin, Wa, and Shan.

It could be expected that the Karenni, Chin, Karen, and Kachin EAOs have joined the conflict in order to expand their control areas and seize new townships, strategic border gates, and trade routes. At the same time, the respective EAOs would likely be considering some defence mechanisms to prevent other armed forces from encroaching into their control areas. We are likely to see ceasefire agreements or cooperation agreements among different armed groups in Shan State, similar to the Restoration Council of Shan State (RCSS) and the Shan State Progressive Party (SSPP) ending hostilities and entering into cooperation agreements with each other or with other EAOs for regrouping and other alliance-formations. Some radical groups, particularly among urban Bamar youth, who emerged during the ‘Spring Revolution’, have been politically active alongside the ‘Operation 1027’ fighting and have vowed for a three-stage objective: (1) Support EAOs to reclaim and liberate their respective lands, (2) Build a new coming-together federal union from these lands, with each having equal status, and (3) In the case of individual ethnic groups not wanting to join the new union, allow for them to choose formal secession instead.

The participation of these radical groups alongside ‘Operation 1027’ has at least lent support to the military operational level as well as the mobilization of the political legitimacy narrative and the wider moral energy of the resistance movement. So far, these radical groups seem to be playing as supporting actors in terms of ‘Operation 1027’s’ strategy, military objectives, and political goals. Nevertheless, the political legitimacy and moral support they bring are crucial for the 3BHA. Without the connection to the Spring Revolution, the public may perceive the 3BHA as merely aiming to regain territory or expand their areas of control. In such a case, the EAOs would still receive support from their respective minority ethnic populations but find it challenging to gain nationwide support, which they currently enjoy. From the international community’s standpoint, these EAOs could be seen as pursuing secessionism or irredentism, making it difficult to support them. As it stands, the interests of the 3BHA leadership and Bamar radical groups may align in both the short and medium terms around the outcomes of ‘Operation 1027.’

In order for radical groups to successfully launch the revolutionary overthrow of the military junta and to win an all-out civil war, at least two or all three of the following conditions must be met: (1)The top military leadership must experience an elite split, a counter-coup, or a critical defection of forces within the military; (2) Major EAOs must form a strategic military alliance to continue fighting against the junta regime; (3) A foreign country or agency must exert effective coercive intervention against the military.

Even if a revolutionary overthrow were to happen by good fortune, the conflict actors would hardly be likely to secure a successful revolutionary transformation. History has shown us that revolutions in Russia, China, Cuba, Iran, post-Soviet states, and the Arab Spring often led to backsliding or were unable to drive social transformation. Myanmar faces an even more challenging task due to its multiple competing armed groups, high levels of poverty, and lack of positive experience in modern nation-building.

One significant theme in ‘Operation 1027’ is the ‘Homecoming of Kokang Brothers’ rhetoric. The word ‘home’ can refer to the place of one’s birth or childhood, a place of cherished memories, or the sentimental home of one’s mother. In such cases, there is little room for problems. However, when ‘home’ is interpreted based on ethnicity or race, or when ‘our home’ is exclusively defined as a nationalistic concept of home, then ‘homecoming’ can become problematic and politically inflammatory. For example, if a resident of Kutkai town wishes to return to their childhood home, it is a lovely idea. But if Kutkai is designated as the home of one particular ethnic group, it could spark tribalistic conflicts since several ethnic nationalities, such as Palaung, Shan, and Kachin, might be residing in the same township and claiming an exclusive sense of belonging and ownership. If the concept of home is defined by ethnicity, such rhetoric could lead to discrimination and conflict over who is the homeowner (the host) and who is the guest. The hospitality of a homeowner is presumed to be conditional, and problems could arise over perspectives such as ‘the guest should not insult the homeowner’ or ‘the guest shall not assume a dominant position.’ This perspective is parallel to the ultra-religious and nationalist group ‘Ma-Ba-Tha’ since the group has advocated for discriminating between ‘Buddhist homeowners’ and ‘all other guests.’ Therefore, even the first step of the Three Stage objective formulated by the radical Bamar youth groups, reclaiming their ‘own’ land, is easier said than done.

Observing public statements made by the leadership of 3BHA forces, their political objectives are unclear. In an open letter to the public dated October 27, despite mentioning the objectives of ‘striving relentlessly to eradicate the oppressive military dictatorship, to pursue national equality, and to construct a new peaceful and prosperous federal democratic Union,’ none of the constituent 3BHA forces subscribe the ‘Federal Democracy Charter’ adopted in collaboration with the National Unity Consultative Council (NUCC) and some EAOs, such as Karen, Karenni, and Chin. The October 27 open letter clearly defined the political situation as ‘our country turns out to be a government-less nation since the military coup.’ The 3BHA joint public statements for ‘Operation 1027’ did not use the term ‘federal democracy.’ The lack of use of the term is quite significant. Since the National League for Democracy (NLD) won the general election in 2015 to a time before the coup in 2021, the 3BHA’s joint statement regarding government did use terms such as “to successfully establish a federal democratic country”. This likely means that their political goals have changed. Instead, their ‘Operation 1027’ statement read “to protect the people’s livelihood, to self-defense, to control more of their region, to prevent airstrikes and heavy attacks by the SAC on our groups day and night, and to eradicate the military junta regime.” This agrees with the Arakan Army (AA)’s openly stated aspiration for confederation status in Myanmar. The 3BHA approach can be read as demonstrating a pragmatic political culture, one rather dissimilar to the approach of the NUCC. This may be because the 3BHA wants to avoid over-politicized and under-strategized plans.

∎ Scenario Forecast

If the Operation 1027, which is conducted by the allied forces, is successful in occupying a satisfactory number of territories, expanding their sphere of influence, and controlling economically significant areas and transport routes, then the operation’s momentum could rapidly slow or even come to a halt. If the United Wa State Army (UWSA) and Kachin Independence Army (KIA) were to actively collaborate with the 3BHA operation, unless they pursued their own military or political objectives, the combined resistance could lead to an all-out (a total) civil war. Therefore, it is crucial to closely monitor how larger armed groups, such as the UWSA and KIA, decide to act, as it demonstrates one of the most important ‘signaling effects’ of the armed resistance. If the 3BHA and other major Ethnic Armed Organisations engage in the conflict with limited objectives, even if restrained or entered a truce due to various reasons, including pressure from China, they can still support the People’s Defense Forces (PDF) and Local Defense Forces (LDF) under their sphere of influence. This support could strengthen a strategy to wear down and weaken the junta military. Finally, in the event that ‘Operation 1027’ does not lead to an all-out (a total) civil war, the outcomes of the operation could lead to a ‘protracted war.’ In such a scenario, other resistance forces could seize the opportunity and momentum, intensifying pressure on the junta’s military forces, weakening junta military control over certain areas, and ultimately shrinking the total amount of territory under junta control.

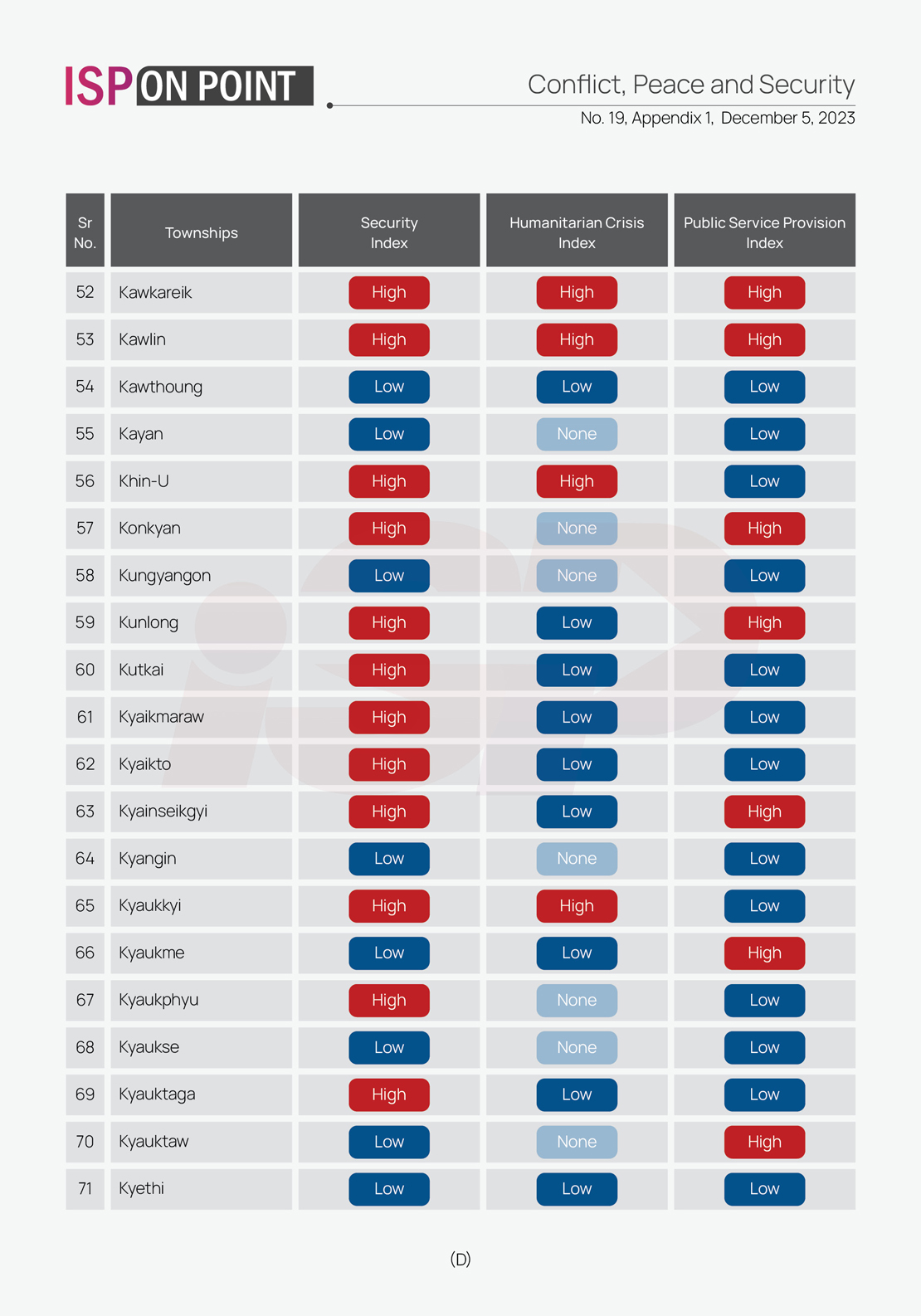

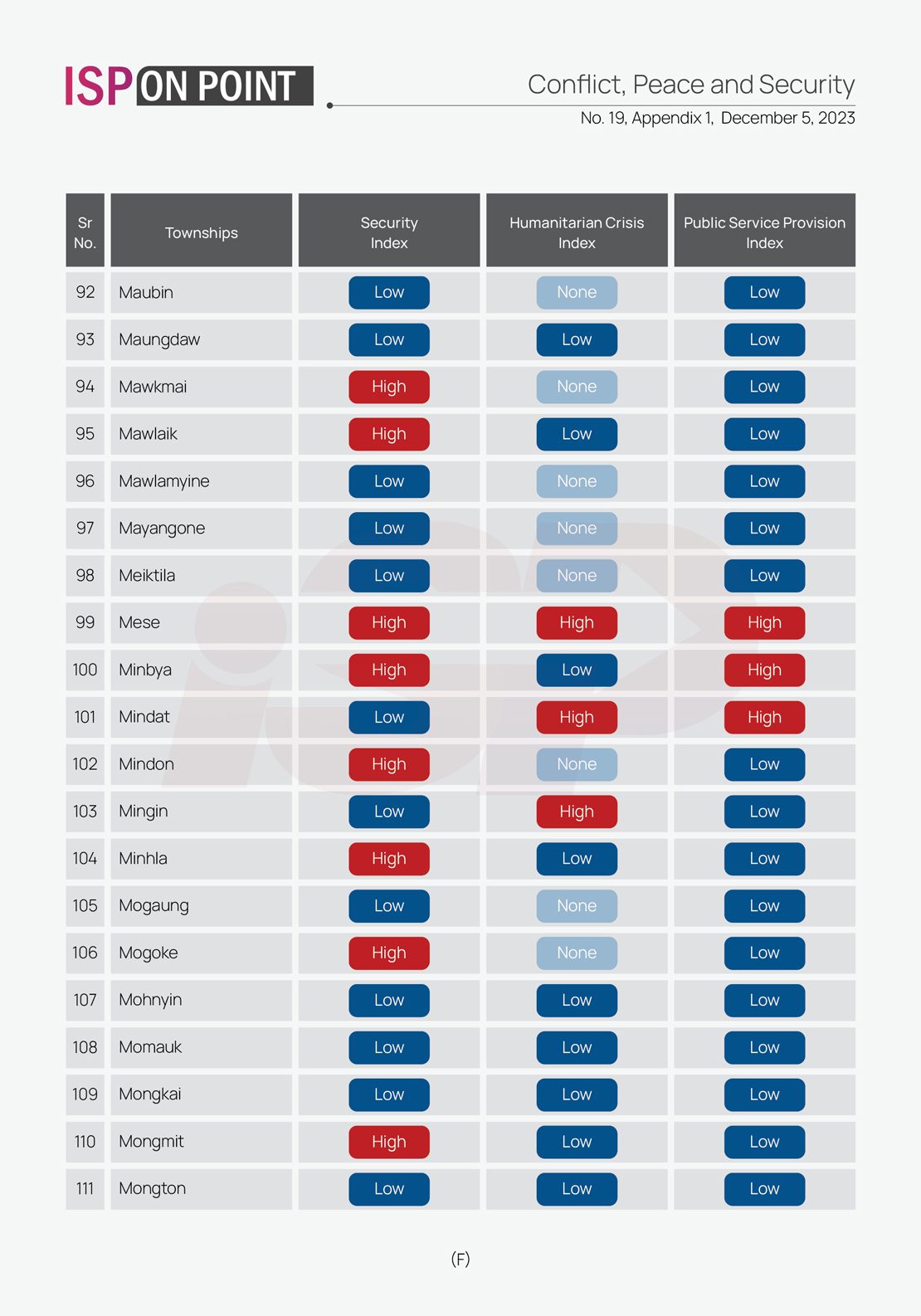

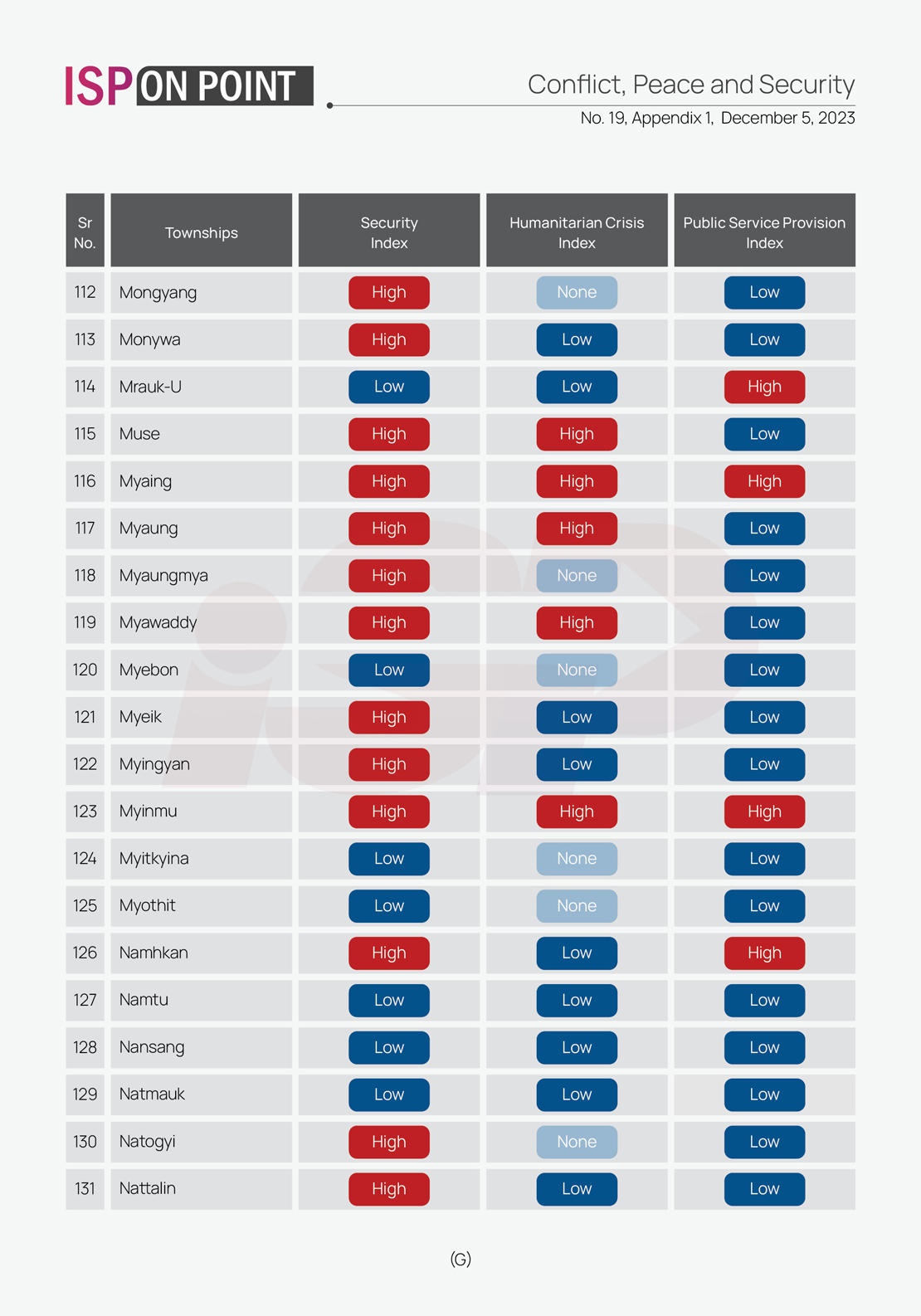

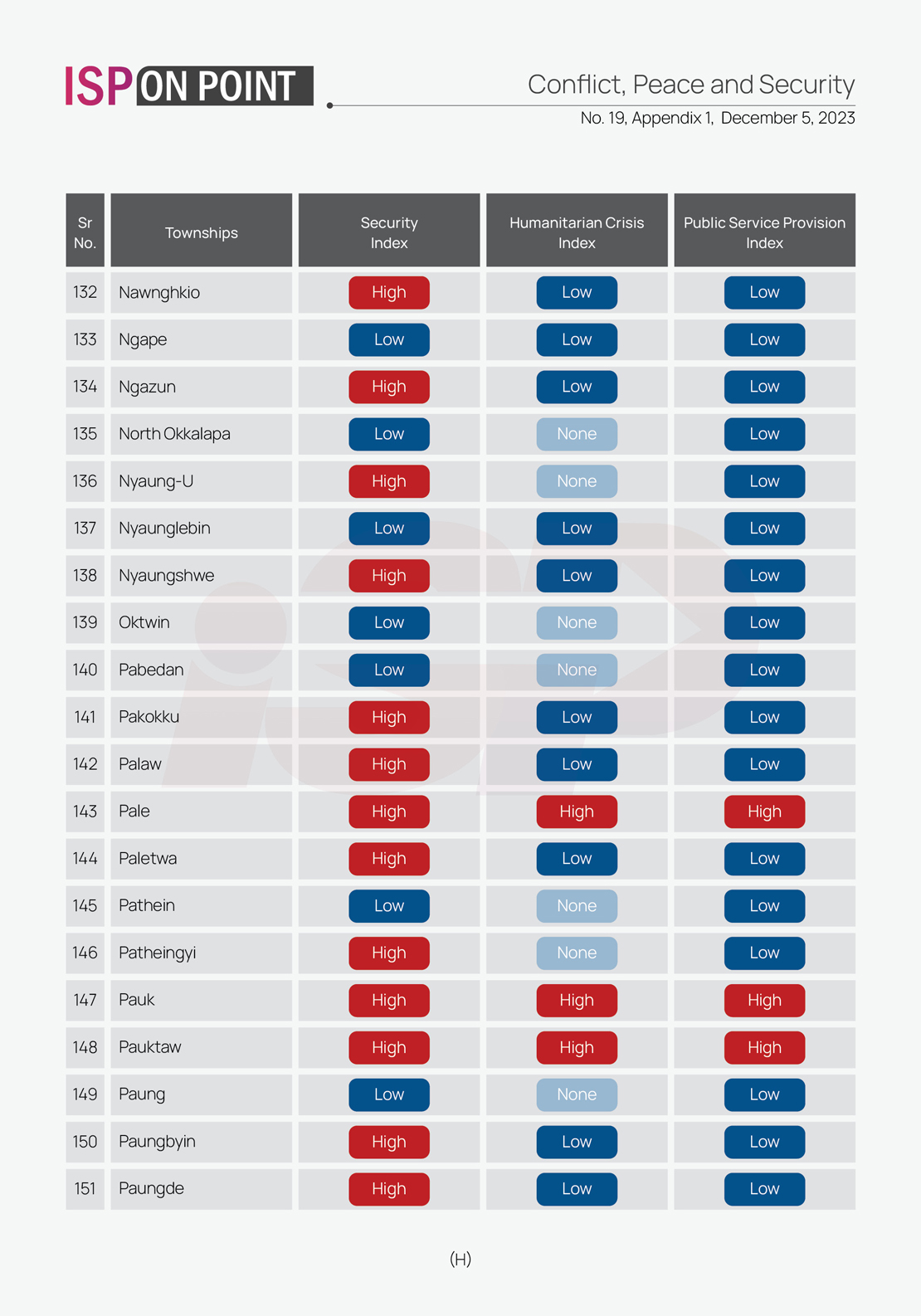

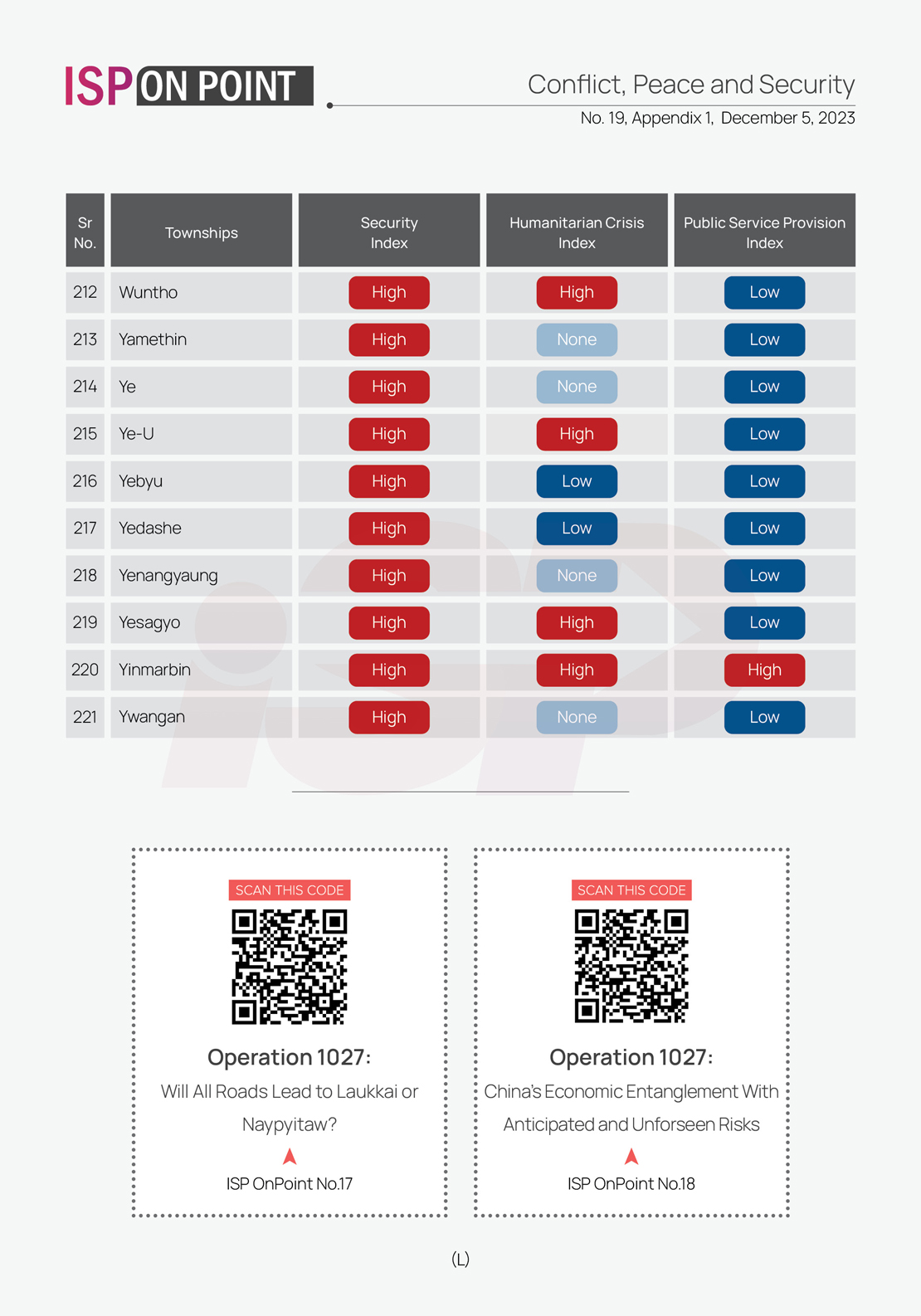

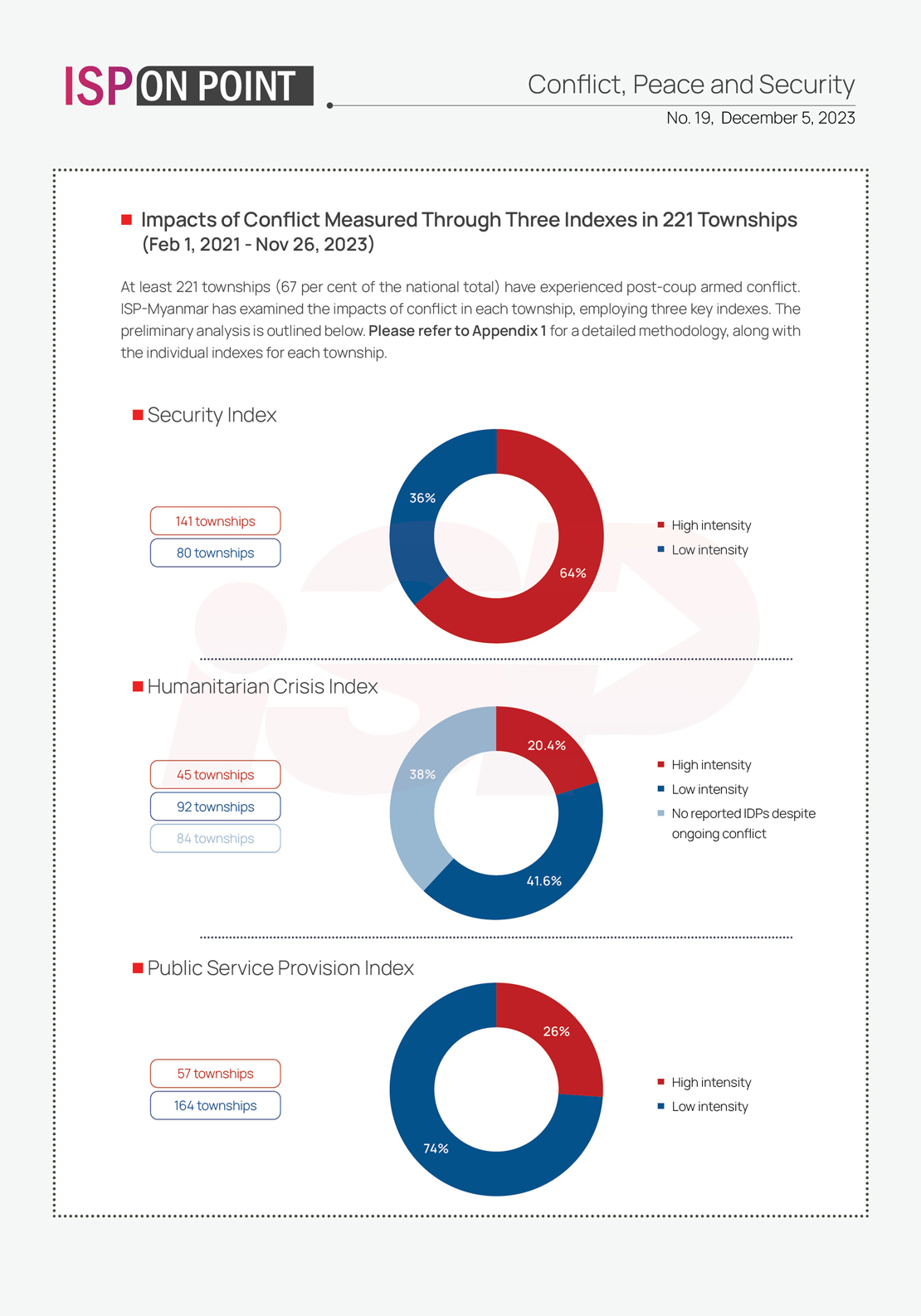

According to data collected by ISP-Myanmar, armed conflicts have taken place in 221 out of 330 townships in Myanmar, which amounts to 67 per cent of the country. The data was collected two months before the third anniversary of the military coup. ISP-Myanmar has developed three indexes to measure the impacts of conflicts in the affected townships. The three indexes are the Security Index, which measures the number of clashes per township, the Humanitarian Crisis Index, which measures the number of internally displaced people per township, and the Public Service Provision Index, which measures whether the township police offices and General Administration Office offices are open, whether basic service provisions such as electricity and water supply are available, and whether bureaucratic personnel still receive salaries.

Of the 221 townships defined as in conflict, 141 can be categorized as having a high-security index, while 80 townships scored low on the Security Index. In terms of the Humanitarian Crisis Index, 45 townships scored highly while 92 townships were classified as low intensity. There are 84 townships where fighting occurred, but no new internally displaced persons (IDPs) were reported. The Public Service Provision Index reports that 57 townships were severely impacted, while 164 townships had lower levels of impact on public service provision. According to the Security Index, the junta military has lost effective control of 43 per cent of Myanmar’s territory. (See Appendix No. 1 for ISP Myanmar’s index data.)

The current military situation may lead to diminished control areas for the junta. Although the junta military can still strategically abandon remote bases, consolidate forces in core areas, and even engage in a counter-offensive, it is unlikely to recover the popular support it needs. Moreover, the crisis and multiple shortages facing the economy can no longer be disguised. The humanitarian crisis could also deteriorate even further. During the ‘Operation 1027’ period, over 300,000 people were forced to leave their homes, and the total number of IDPs created by the fighting since the military coup has now exceeded four million.

In this context, it is crucial to shape a new political imagination, to build a new inclusive political home, like the “land of the free and home of the brave”. Practical commitments and guarantees from the major resistance forces are needed to determine the future configuration of the new nation-state. Without such aspirations and agreements, the situation could spiral out of control, allowing more radical groups to achieve their goals. The radical resistance group’s ideal aspiration is (1) supporting EAOs in reclaiming and liberating their respective lands, (2) building a new coming-together federal union from these lands with equal status for each, and (3) allowing individual EAOs to choose formal secession if they do not want to join the new union. However, the current military situation favors each of the individual resistance forces acting alone, which could lead to skipping the Stage-2, which is ‘coming-together federal union-building’, and directly lead to Stage-3, which is ‘fragmentation’, if each group takes advantage of the circumstances favorable to themselves.

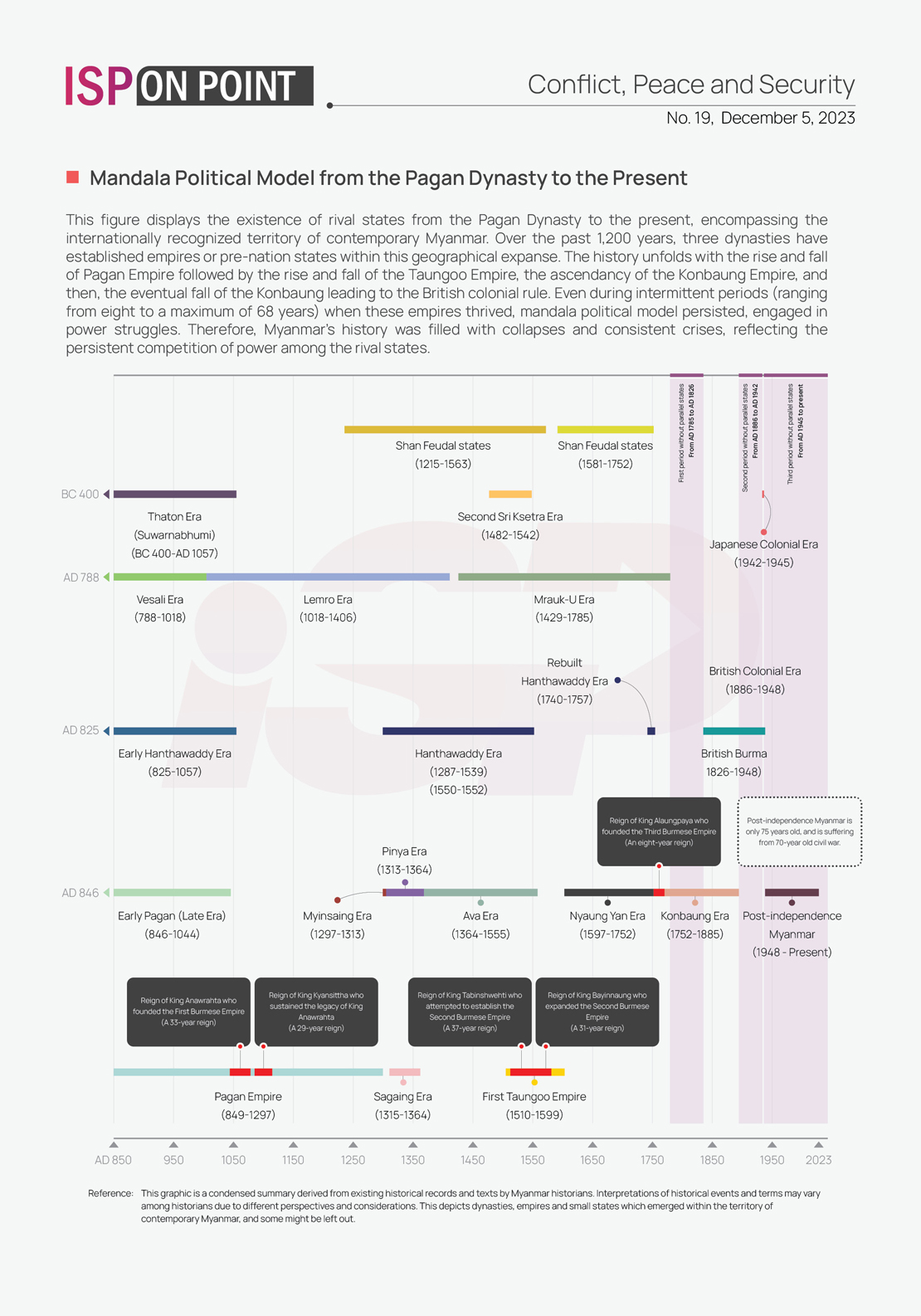

Armed groups, especially the EAOs, tend to favor members who are loyal to their own group based on ethnicity, race, or political affiliation. This preference can lead to the creation of small states or quasi-states in local areas, where the group controls the centralization of power. These mini-states then would exercise territorial control, demand loyalty from rival armed groups, establish administrative mechanisms to manage tax collection systems, provide basic services in a preferential or discriminatory manner based on ethnic, regional, and political affiliations, and promote ethnocentric identity discourses. In such a scenario, political power in Myanmar could be diffused among many competing principalities, or ‘mandala political model’. The discourse surrounding such a scenario is different from the concept of ‘local governance’ imagined by international humanitarian agencies and NGOs. Rather than local governance within a wider state, this would merely be mini-state or quasi-state building in a fragmentation scenario.

The study of Myanmar’s history reveals a pattern of rising and falling powers. From the decline of the Pagan Empire to the rise of the Taungoo Dynasty, from the fall of Taungoo to the emergence of the Konbaung Empire and then the fall of Konbaung, the history was marked with division and the emergence of competing principalities, known as ‘mandala political model.’ Much of the country’s history involved small competing kingdoms, political crises, and political declines and collapses. Throughout, the feudal and ruling elites’ legitimacy has never been based on modern nationalism, and the relationship between the rulers and the ruled was simply that of patron-client relations. However, in the present context, the concept of ‘home’ is now seen through an exclusive nationalistic lens. This has led to the extension of control by powerful armed groups, driven by their respective exclusionary nationalistic objectives in a multiethnic polity, which has the potential to ignite tribal conflicts. Similar to the ongoing grievances of minority ethnic groups resisting Burmanization within a union with the majority Bamar polity, numerous regions in Myanmar might witness similar tensions. Various armed groups who are or become dominant in a region and who do not necessarily constitute a majority in those areas could spark similar conflicts.

Thus far, it seems that some local and international supporters, who are still enamored with conflict, agree with Edward N. Luttwak’s famous words ‘Give War a Chance’1.

1 Luttwak, Edward N. (Jul-Aug 1999). Give War a Chance. Foreign Affairs, Vol. 78, No. 4. pp. 36-44. Council on Foreign Relations

Many portray ‘the illusion of hell’ as ‘divine rewards’ and so let them. Instead of imposing untimely solutions, the effective approach should focus on:

(1)Providing humanitarian aid and protecting civilians to mitigate the adverse effects of conflict from a conflict mitigation perspective.

(2)Encouraging interdependent community building that can prevent tribalistic conflicts from arising due to ethnic-based mini-state or quasi-state building and the formation of ethnic enclaves. Then allow the resulting vibrant civil society to at least provide basic public goods to needy populations.

(3)Establishing communication channels and coordination among the conflict parties. If the time ripens for international mediation, these could serve as an effective base for negotiations.

One possible glimmer of hope lies in the potential development of solidarity among various armed groups, including EAOs from different regions and comrades-in-arms who have come together to fight a common enemy. Through cooperation and sharing knowledge, they may be able to establish mutual trust. For example, Bamar civilian groups donated 500 million Kyats to the MNDAA during the conflict, which would likely encourage goodwill and foster confidence among the Kokang population. Similarly, some resistance groups have adjusted their policies to gain local support and recognition from the international community. For example, the Arakan Army (AA) has started using the word ‘Rohingya’ and softened its policies to a more pragmatic level. If these practices are integrated into the state-building process, it could lead to a positive development of political socialization. This could help to build a political culture that is more sensitive to norms and principles. Yet the process of political sensitization of norms and principles is rather weak and slow-paced when compared with the potential for mini-state or quasi-state building, or the trend towards militarization. It is crucial to curb the glorification of military might and the deterministic pursuit of military victory in all aspects..

As previously suggested, our current focus as local and international communities should be on mitigating the severe consequences of armed conflict, promoting interdependent community building, and raising awareness of political norms and values. This includes developing civilian-led local governance, safeguarding freedom of speech and press, opposing any laws or regulations that promote discrimination or social conflicts, and ensuring the protection of women and children’s rights. Additionally, we must avoid over-extracting natural resources, as it can have detrimental effects on the natural ecosystem.

As mentioned earlier, both Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs) and revolutionary forces share the desire to bring about positive change and develop better systems. Soldiers could engage in endogenous political learning, which involves learning from each other. Likewise, Civil Society Organizations (CSOs), media, academics, international organizations such as the United Nations (UN) and Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), foreign governments, and support groups could enhance the knowledge and practice of exogenous political learning by collaborating with EAOs and revolutionary forces. This approach, in Daniel Ritter’s words, would create an ‘iron cage’2 of international norms around the conflict actors.

2 Ritter, Daniel. P. (2014). The iron cage of liberalism: international politics and unarmed revolutions in the Middle East and North Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

At the same time, we must be cautious against the deceptive optimistic views of liberals and radicals who believe that “all good things go together.” In the realities of a complex political world, which is often characterized by naked power and vested interests silencing the norms and values, such an optimistic scenario could hardly be realized. The warning bell from ‘Operation 1027’ rings loud and clear that Myanmar needs a new political imagination that aspires toward an all-inclusive state. It also needs a new political roadmap consisting of pragmatic steps through which conflict forces can strategically progress sequentially.