On Point No. 20

(This ISP OnPoint No. 20 (English version) is published on February 20, 2024 as a translation of the original Burmese version published on February 16, 2024.)

∎ Events

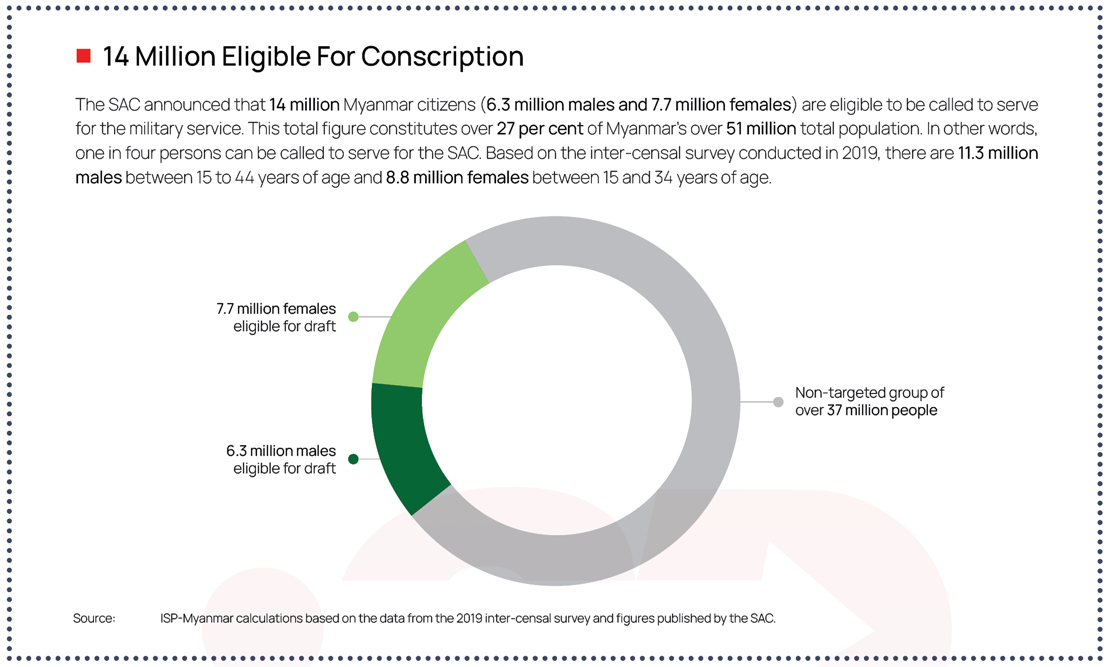

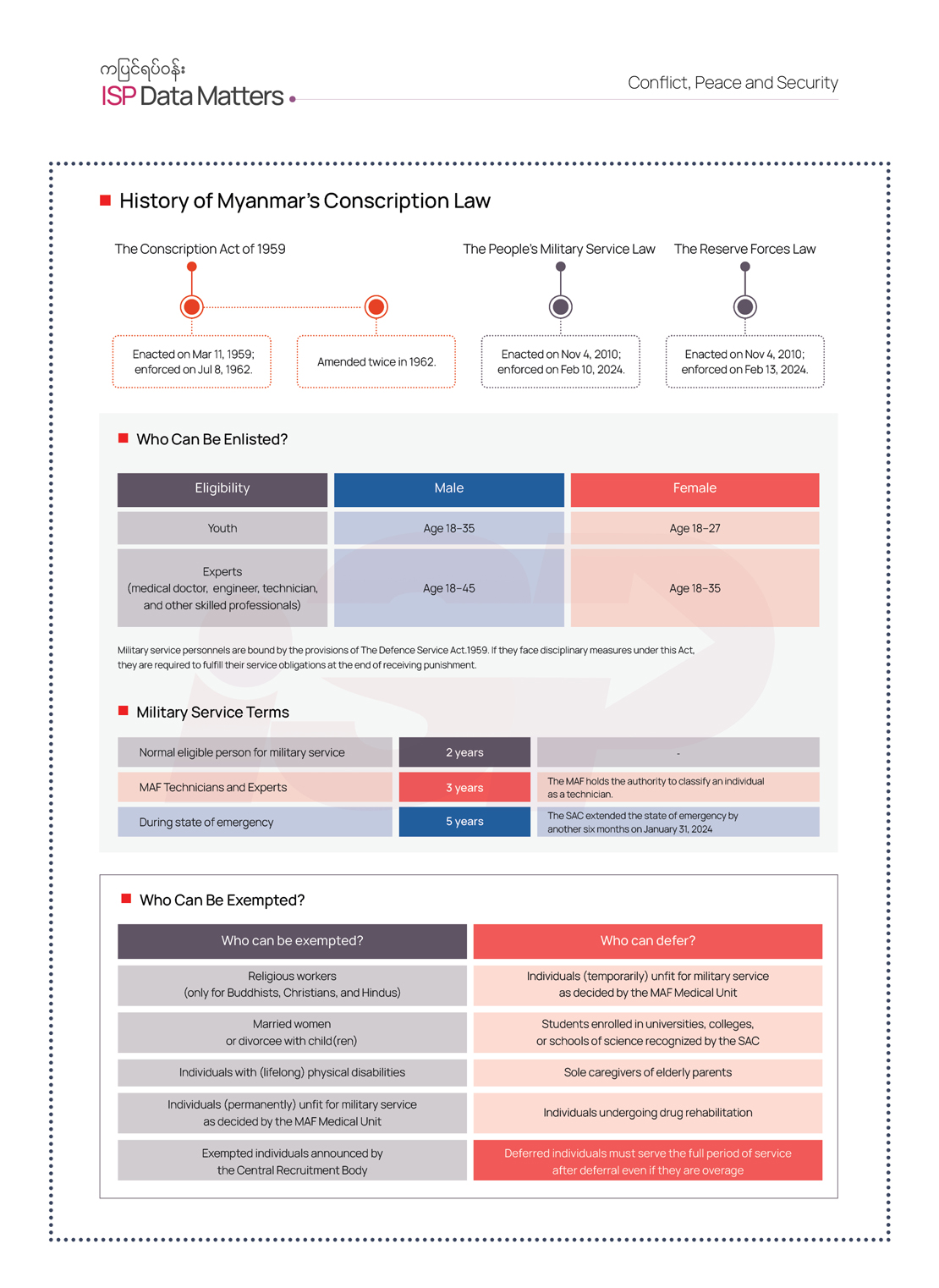

The State Administration Council (SAC) declared the enforcement of “the People’s Military Service Law”*, which is commonly known as the conscription law, on February 10, 2024, which requires all male citizens aged 18 to 35 and all female citizens aged 18 to 27 to perform mandatory military service in the junta armed forces. Despite the absence of active warfare with other nations, in light of the junta’s unprecedented losses amid post-coup conflict, the declaration of this conscription law has fueled panic among the country’s 14 million youth and their families.

*More details about the law are discussed in the later section of this OnPoint.

On February 13, the SAC established the Central Body for Summoning People’s Military Servants (the central recruitment body) to oversee implementation of the conscription law, revealing plans to commence in April, with each cohort comprising 5,000 recruits and a total of 60,000 annually. The “Reserve Forces Law,” which mandates the recall of retired soldiers for service, was also proclaimed effective on the same day.

∎ Preliminary Analysis

A three-part analysis can be done regarding the SAC’s recent activation of the conscription law. The first part highlights the necessity for the Myanmar military to implement the mandatory military service law, primarily driven

by the need to recruit soldiers in response to their depletion and the inefficacy of previous recruitment methods, compounded by diminishing public support. The second part of the analysis focuses on how the SAC will implement the law. The third part examines the five negative potential consequences following the implementation of the conscription law in the conflict-prone Myanmar:

1.More widespread human rights violations under increased oppression;

2.Increased corruption and extortion at all levels of the regime;

3.The possibility of mass migrations;

4.Escalating divisive tensions along racial, religious, and regional lines, as military recruitment will target rural and impoverished Burmese and tribal youth in regions where no ethnic armed organization present;

5.The likelihood of youths, especially in conflict regions and nearby, joining Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs) or the People’s Defense Forces (PDFs).

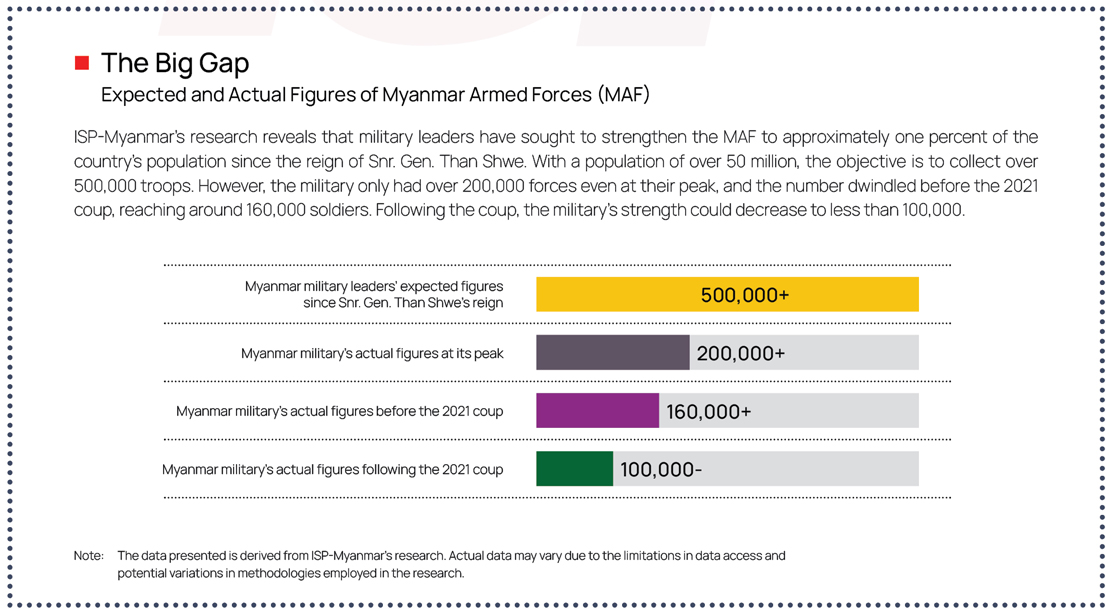

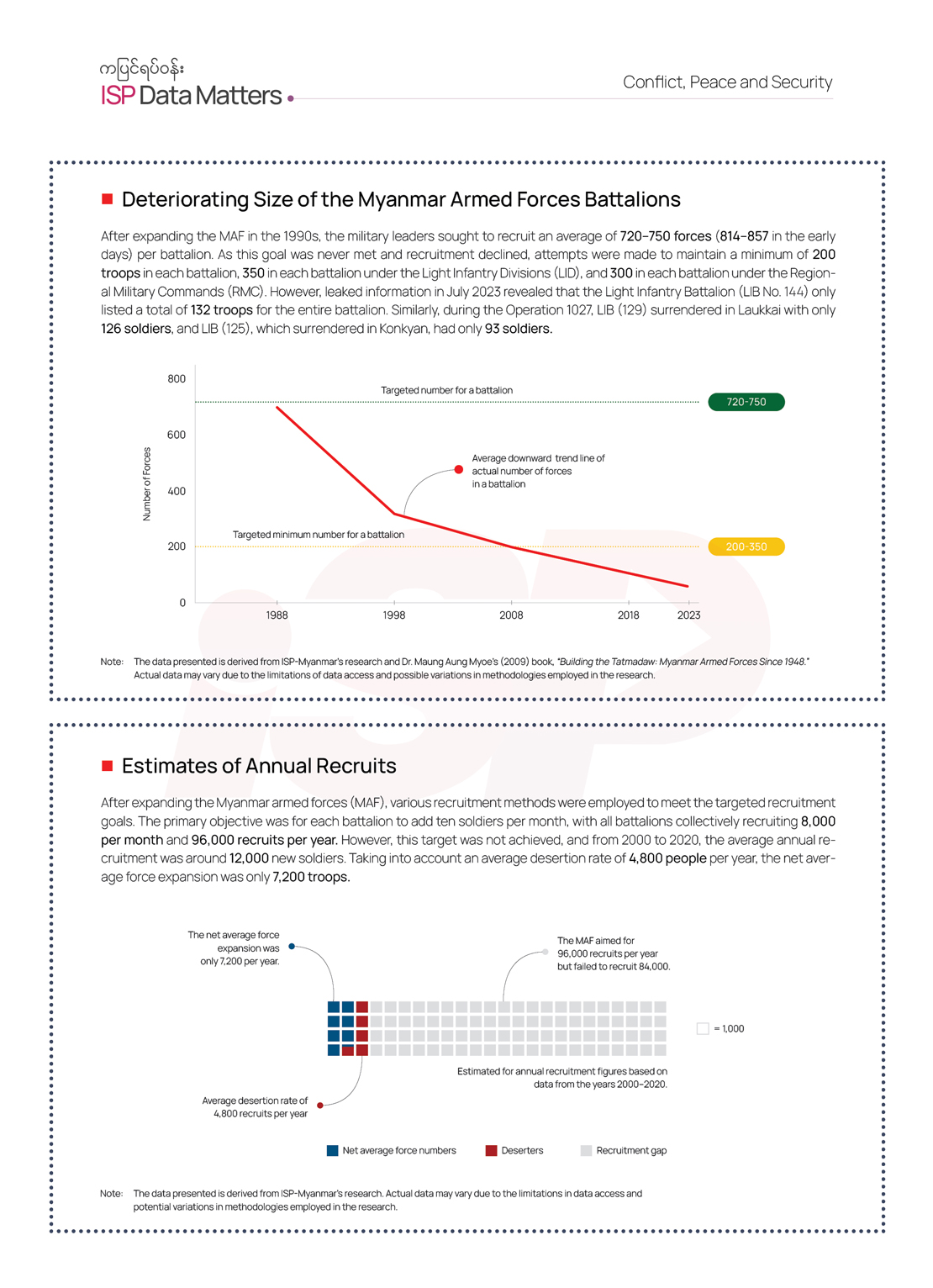

ISP-Myanmar’s research reveals that military leaders have sought to increase Myanmar’s Armed Forces (MAF) size to approximately one per cent of the country’s population since the reign of Snr. Gen. Than Shwe in the early 1990s. With a population of over 50 million, the objective is to collect over 500,000 troops. An ideal battalion was to be made up of about 720-750 (814–857 in the early days) troop members including 30–60 officers. However, no battalions were fully formed as planned since then. When the target was not achieved, each battalion was ordered to recruit at least ten new soldiers every month. At that rate, the combined army, air force, and navy, consisting of over 800 battalions, would require to recruit at least 8,000 new soldiers per month. Again, this goal was never realized. During the years 2000 to 2020, an average of approximately 1,000 recruits were enlisted per month. With voluntary enlists declining over time, these low recruitment numbers were mainly achieved through forced conscription and buying and selling by army recruiters. Meanwhile, among the recruits, the desertion rate averages around 400 individuals per month, resulting in a net of only 600.

The Office of Adjutant General determines the deployment of the newly recruited troops after their training is complete. The battalions may not automatically end up filling their recruitment quotas with the new soldiers they recruited. The Office of Adjutant General prioritizes requirements for battalions with fewer than 200 soldiers, indicating that average military battalions aim to hold at least 200 soldiers.

Additionally, each battalion under the command of Light Infantry Divisions (LID) is expected to maintain around 350 soldiers to reach full force capacity. After that, battalions under Regional Military Commands (RMC) are aimed to fill with around 300 soldiers. New recruits who finished middle school level (eighth grade in public education) are often selected and reassigned to the technical and non-combatant support corps as needed. Despite using various recruitment methods, ISP-Myanmar’s research found that the Myanmar military had only over 200,000 forces at its peak. This number dwindled even before the 2021 coup, reaching around 160,000 soldiers.

The force’s number further declined after the coup due to casualties, health problems, desertions, and joining the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM), resulting in fewer than 100,000 troops. For the army to replenish this depletion and regain its previous military strength, approximately 100,000 new soldiers are needed. An additional 400,000 soldiers are required to meet their original goal. The enforcement of mandatory military service is notable against the backdrop of the military’s lack of public support and failures in recruitment. The SAC said they aim to enlist 5,000 new recruits monthly, starting in April 2024, and thus 60,000 yearly. Examining this, it appears that the objective is to restore the military’s strength to pre-coup levels within the first year of recruitment.

Although the conscription law has been activated, its implementation process will take time. While the central recruitment body was formed within days of enactment, lower-level committees are yet to be formed, and detailed by-laws and procedures are yet to be declared and enforced. Preparation time is needed to identify the list of eligible individuals who fit the enlisting criteria for military service. Additionally, establishing institutions at the central, region/state, township, and ward/village levels to compile the recruits, and establishing a new directorate within the military to oversee training and assign duties to the conscripted individuals are also parts of the preparation process. Interdepartmental cooperation is also needed, as well as additional defense budget must be allocated for the new recruits. Therefore, the SAC spokes-person mentioned that the training of the first cohort will be conducted after the Myanmar New Year Water Festival (Thingyan Festival) in April. The next steps after completing the list will be summoning through conscription notice letters and conducting medical checks, which could take around two months. Therefore, the first cohort might commence training as early as June and as late as August. If the training duration can be considered four to five months, the training for the first cohort will conclude either in November, December 2024 or in January 2025.

∎ Scenario Forecast

For Myanmar’s Armed Forces (MAF), which is facing humiliating defeats in recent conflicts, solely relying on recruiting new personnel without contemplating reforms in the leadership and strategy of the security sectors will not work. The entire national security and defense policy and the whole vision of the military will need to be restructured. A comprehensive political framework that instills belief in democracy and a federal vision for all citizens has yet to be established. Without these policies and framework in place, the forced conscription of citizens could potentially strain the relationship between the whole Myanmar society and the MAF to a point where it is completely irreconcilable.

The first potential consequence of implementing the conscription law during the peak of the civil war is widespread human rights violations. Such violations are likely to occur throughout the recruitment, training, and deployment phases. Individuals may face oppression and discrimination based on factors like place of residence, age, ethnicity, faith and religion, economic status, and gender orientation. Currently, there are reports of the military abducting people and forcibly recruiting in certain areas. While the SAC has dismissed some of these reports as false information, the conscription law could legitimize such incidents.

A second potential consequence is that this law will open avenues for bribery and corruption at all levels within the regime, affecting the entire society. Incidents of bribery between individuals seeking to evade military service and civil-military authorities may become widespread. There is no sustainable way to curb such corruption in Myanmar. In other countries, cases of corruption often arise during the process of determining individuals unfit for military service or in attempting replacements.

A third potential consequence is the mass migration of working forces to neighboring countries, leading to brain drain. Individuals with the financial means and access to opportunities are seen massively leaving the country within days of the law taking effect. The Royal Thai Embassy in Yangon has announced that it can only process 400 visa applicants per day as massive applications rush in (Thailand is the immediate or temporary popular destination for people from Myanmar). In addition to leaving the country through this avenue, some individuals may opt for illegal means to leave the country and considering that the law also applies to expatriate citizens, some may even go so far as to permanently leave the country. Myanmar’s mass migration combined with current nearly five million conflict refugees may pose a threat to regional stability.

Based on the 2019 intercensal survey, Myanmar has around 1.6 million people employed overseas (accounting for over three per cent of the nation’s population). Among these, two thirds opted for Thailand as their destination. As per the World Bank’s report in 2017, five per cent of Myanmar’s population has migrated abroad, making it one of the highest outbound migration rates in Southeast Asia. In a report published by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) in March 2023, it was revealed that 3.6 million people in Myanmar, equivalent to 6.5 per cent of the country’s population, relocated during the six months under examination. Among these, more than 604,000 fled due to conflicts, while over two million relocated in pursuit of employment.

Data from ISP-Myanmar’s monthly socio-economic survey covering 110 townships across the country also indicates similar trends. In 2023, 85 townships out of the 110 townships studied across the country (approximately 77 per cent) reported a consistent outflow of migrant workers seeking job opportunities abroad. Concurrently, the number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) due to conflict has been pushing to five million (as of January 2024). Among these displaced individuals, a significant portion comprises young labor forces. Consequently, the implementation of the conscription law might potentially exacerbate the country’s labor shortage problem due to increased emigration and evasion abroad. This could severely impact Myanmar’s already weakened economic production sectors, and the substantial migration and departure from the country may lead to significant capital outflows and negative repercussions for the weak economy of the country.

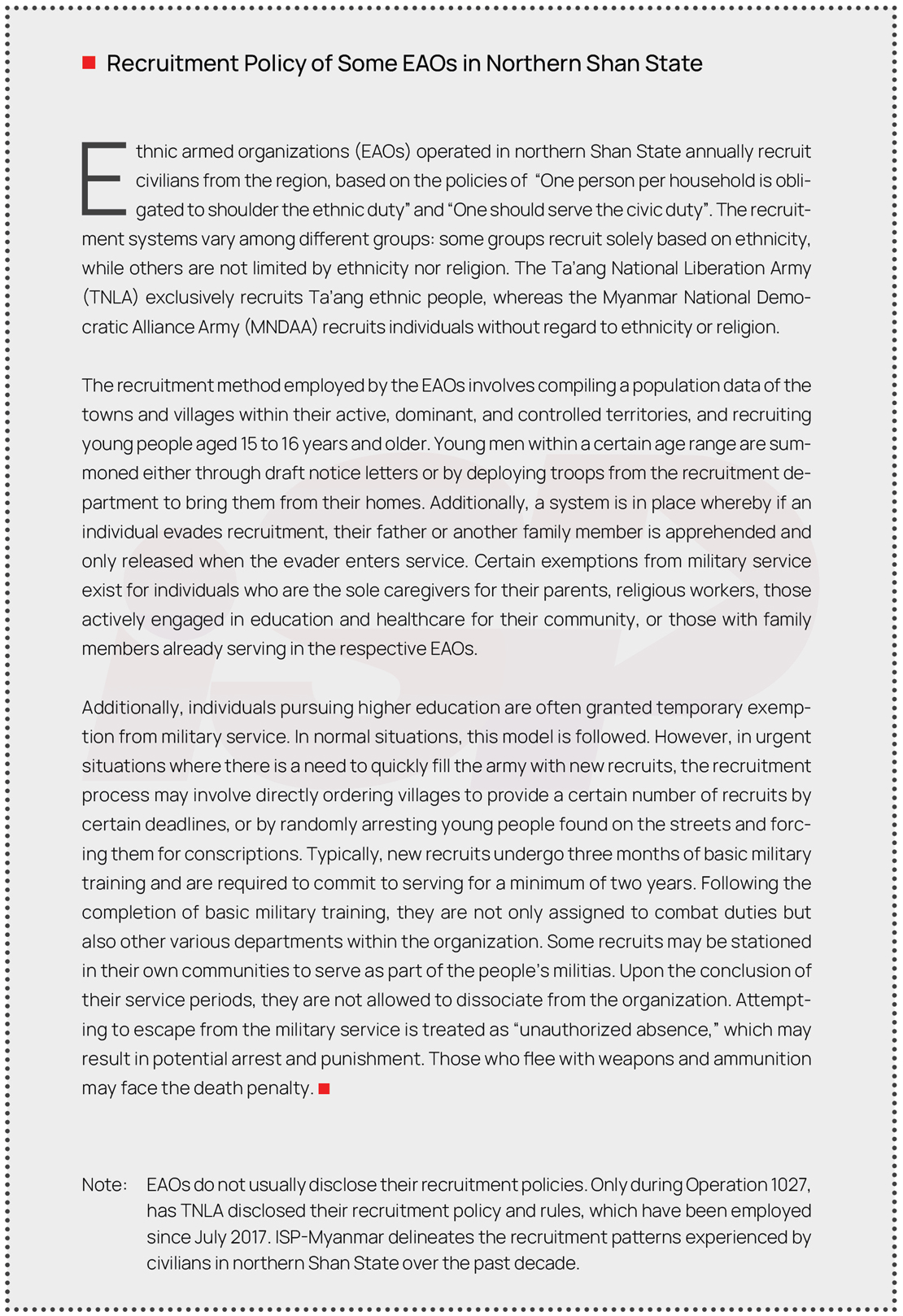

The fourth potential consequence is that recruitment will target primarily young people in rural areas, potentially affecting impoverished youth more severely. At the same time, it could also target Burmese and minority youths from areas with no significant insurgency groups and armed conflicts. Therefore, coercing these young people into military training and deploying them to the battlefield risks exacerbating societal divisions and animosities based on class, race, religion, and region throughout the country. Here, it is worth considering the enlistment of new recruits by certain ethnic armed groups in northern Shan State in addition to the recruitment efforts by the SAC. The Arakan Army (AA) and Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) principally recruit based on ethnicity, whereas the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) recruits individuals from its territory without regard to ethnicity or religion. A system is in place whereby the father or another family member of an individual evading recruitment is apprehended. Those who desert the military can face re-arrest and punishment while fleeing with weapons and ammunition could lead to the possibility of the death penalty. The Shan State Progress Party (SSPP) conveyed a message through social media in Shan language (an ethnic language) that safeguarding a territory requires adequate military strength, urging locals to enlist in their army.

In any scenario, recruitments and deployments of the newly recruited for combat by various armed groups, including the MAF, may affect not only the relations among individuals of different ethnicities and geographies but also of the same populace. For instance, the SAC recently regained control of Kawlin town from the joint seizure of the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and the People’s Defense Forces (PDF), where the National Unity Government (NUG) established administration. In this event, SAC reports narrated that the young and middle-aged villagers formed defense groups and collaborated with nearby military commands to resist the KIA and PDF forces’ oppression and revolt against them. The SAC created these narratives portraying local people resisting the insurgencies and siding with the MAF. According to the provisions of the People’s Military Service Law, recruits, upon completing their training, may choose to serve in the locations and regions of their preference for the specified duration. The ensuing conflicts would involve warfare among each other resulting in adverse consequences for the society, particularly for the impoverished. In this case, racial and social justice fault lines in society would likely widen.

On the other hand, there is a potential for some youths, particularly those from conflict areas, to opt for joining Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs) or the People’s Defense Forces (PDF) groups. For instance, the youths of Rakhine, Chin and Karen ethnicities would rather join EAOs that represent their ethnicities. Youths from the dry zone and areas where the majority is Bamar ethnic would similarly rather join the nearby PDFs or Local Defense Forces (LDFs) where their close friends and acquaintances might be located. In the past, enlisting in the MAF once provided a stable life and salary without warfare. But since the coup, with a high rate of casualties, surrender and desertion and the diminishing public support for the regime means disincentives for young men to lay their lives on the line to support its continued rule. While the SAC asserts that evading the military service law and joining other armed groups is punishable under existing laws, youth in conflict zones often just brush off these threats.

Last year marked the 75th anniversary of independence, similarly, civil war also turned 75 years. However, this year has again witnessed an escalation in conflict. The implementation of the People’s Military Service Law at this juncture could potentially catalyze an expansion and impacts of conflict within society. The fact that ethnic armed forces will be simultaneously compelled to recruit and bolster their military capabilities is also significant. Without focusing on a comprehensive peace process while the military forces are expanding at an accelerated rate and subsequent expansion of conflict, Myanmar’s armed conflict level is unlikely to be reduced in the foreseeable future. Being forced to serve in the military for a set duration – typically at least two years – during one’s youth comes with an opportunity cost at an individual level as well as at the society level. When a nation collectively chooses the path of securitization and militarization, it inevitably incurs an opportunity cost in the development and productivity of the nation, impeding the country’s positive trajectory for generations to come.