Insight Email No. 18

This week’s ISP-Myanmar Insight Email No.18 highlights the World Bank’s Burma Economic Monitor and the fragile status of Myanmar’s economy. We also present the probability of conflict resurfacing in Kachin State along key routes for the military and border trade purposes, and the fighting in the border town of Mese, Kayah State, highlighting a switching of allegiances of the Karenni Border Guard Forces (BGF) against the junta. We then discuss the recent statement of the Three Brotherhood Alliance warning against impeding international (Chinese) investment in areas under their control. Finally, the bulletin examines household indebtedness and the microfinance industry in Myanmar, and introduces a book by Sai Kham Mong, ‘Shan State within the Union of Myanmar’.

∎ Key takeaways

1. A fragile economic recovery

The World Bank published ‘Myanmar Economic Monitor’ in the first half of 2023, and launched the report at the Union of Myanmar Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry (UMFCCI). The report argued that economic activity has been slowly increasing in Myanmar, with a three percent GDP growth rate in 2023. However the report also suggested that Myanmar’s economy was in ‘a fragile recovery’, with a long way back to return pre-Covid pandemic levels of economic activity. The Economic Intelligence Unit’s (EIU) recent report estimated GDP growth lower than the World Bank, with only 1.5-2 percent in the 2022-2023 financial year.

Reasons for this economic fragility include the worsening conflict, greater slumps in electricity generation, persistent inflationary pressure, and further deterioration in the business environment. Cyclone Mocha is also a reminder of the Myanmar economy’s vulnerability to climate change. Economic activity could also be limited by severe supply and demand constraints. Meanwhile, the limited growth that exists is unequal and the benefits of this growth are distributed unevenly. The report also warns that ‘food security and nutrition appear to have worsened during the first half of 2023.’ EIU’s report analyzed that Myanmar’s export potential declined by 15 percent year on year, adding to the decline of revenue from natural gas exports. The trade deficit has widened significantly as the value of imports only rose 6 percent in the same period. The trade balance shows negative USD 1.4 billion in the second quarter of 2023 (to June). The weak economic and political institutions of Myanmar could lead to over-reliance on extractive economies in the near future.

On July 2, SAC Chairman, General Min Aung Hlaing chaired a meeting at the UMFCCI on the matter of national economic promotion. General Min Aung Hlaing stated that the SAC’s national agenda centres on the nation’s welfare and food sufficiency. But the meeting did not show any movements towards the much expected liberalization of foreign currency controls. The SAC still strictly maintains a policy of 65-35, which means the export earner must convert 65 percent of their foreign income into Myanmar Kyat at the government prescribed rate with the other 35 percent to be used at the market rate. General Min Aung Hlaing also suggested that if Myanmar meets its production target, the country will have 249.5 percent oil sufficiency, and that palm oil imports for consumption will be banned in 2025.

To avoid dependency on the US dollar in trade settlement, from August 1st, the SAC will allow border trade settlement in Chinese RMB, and also for customs to be levied in RMB. On June 21, the US imposed sanctions against two state banks, Myanmar Foreign Trade Bank (MFTB) and Myanmar Investment and Commerce Bank (MICB), the impact of which has been profound in the open market, with the exchange rate to USD reaching 3,100 Kyats. To control the situation, Myanmar’s Central Bank introduced a system of online trading on June 23 and allowed currency trading at a rate of 2,900 Kyats to the USD for authorized dealers. The state imposing such financial controls though could lead to worsening trade conditions, while not freeing Myanmar from USD dependency in foreign trade.

2. Probability of conflict resurfacing in Kachin State

The conflict in Kachin State has reignited between the forces of the State Administration Council (SAC) and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), with the battleground primarily focused on strategically vital roads for both military operations and border trade. It is reasonable to speculate that the SAC aims to assert complete control over these key transportation routes.

The intensity of the conflict between the forces of the State Administration Council (SAC) and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) is escalating around Nam Sam Yang village. This village, located a mere six miles from the KIA headquarters in Laiza, holds significant strategic importance as it lies on a key border trade route to China as well as on the Myitkyina-Bhamo road connecting the headquarters of SAC’s Northern Military Command with the No. 21 Sector Operation Military Command based in Bhamo.

In 2011, most villagers from Nam Sam Yang village were forced to flee due to the fighting. Later in 2019, at least 500 villagers resettled back under the military-sponsored resettlement program. But the village is still far from being fully rehabilitated, because of the risk of landmines as well as illegal gold mines operating near the village. It is reported there was an informal agreement between Myanmar military and the KIA to designate the village as a ‘no man’s land’ for both forces. Now though, the SAC is trying to take control of the village. On July 4, KIA’s Laiza district administration office warned local travelers not to use the road and to travel with care.

In another event, the SAC’s forces and Lisu militia forces have been advancing to KIA’s Battalion No. 3 area in Sadon Township since June 25, and they occupied KIA’s Lagat Kawng camp on July 4. The intention of the military and Lisu militia is seemingly to control the Sadon-Kanpiketi road, where KIA forces are imposing taxes. During military tensions between the forces, Chinese delegates from the Yunnan Consulate office traveled on the same road on June 27 and the convoy was fired upon. KIA and Lisu militia officials blamed each other for the shooting.

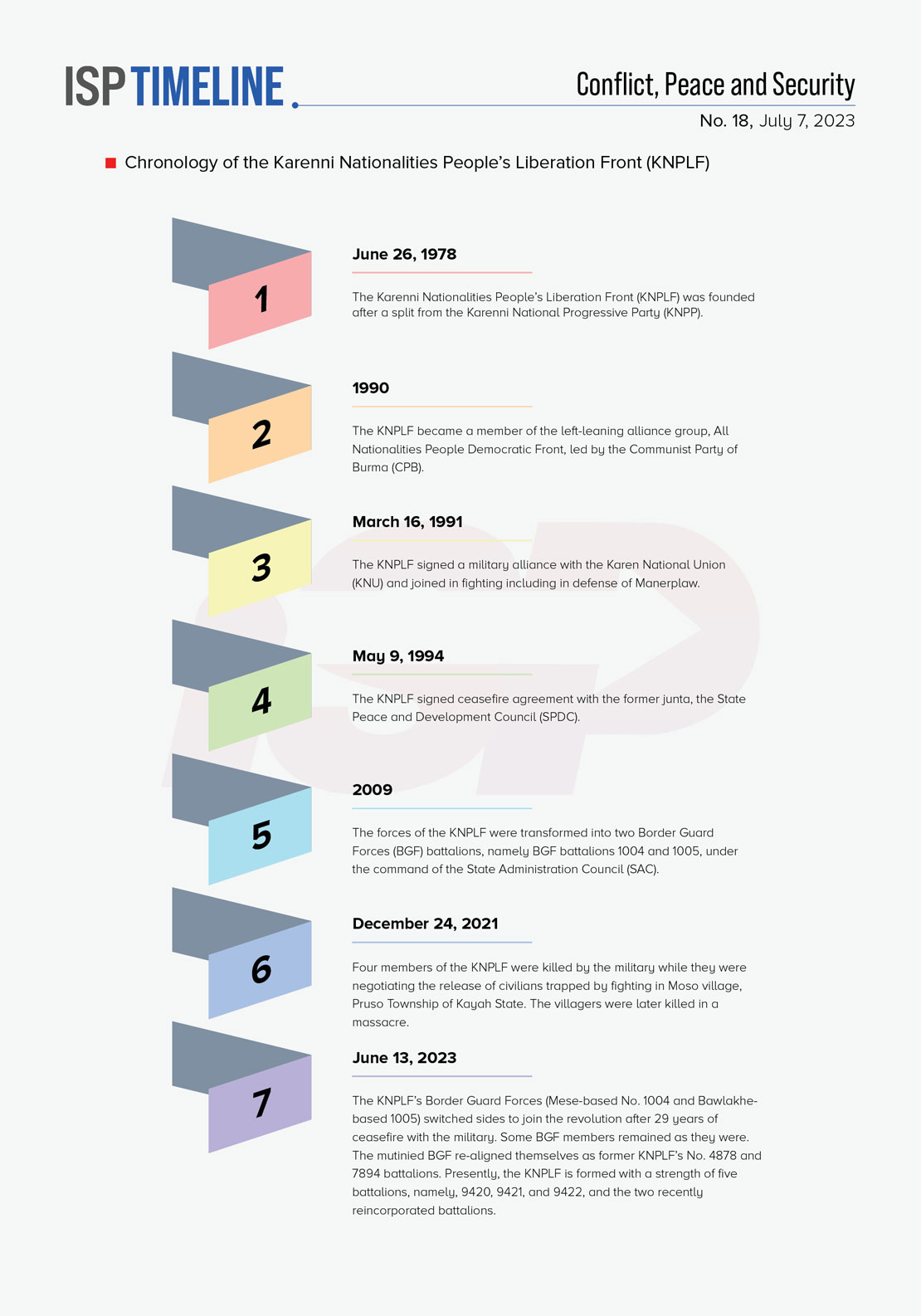

3. Fighting in Mese and the Karenni Border Guard Forces turning against the junta

On June 13, resistance forces operating in the Karenni area successfully seized control of three border base camps and a strategically vital hill in Mese Township of Kayah State. These occupations are particularly significant as two battalions belonging to the State Administration Council’s (SAC) Border Guard Forces (BGF), which were originally formed from the Karenni People’s Liberation Front (KNPLF) back in 2009, made the decisive choice to shift their allegiance and actively participated in the fight against the ruling junta. A KNPLF statement reads ‘we join with other resistance forces to ultimately end the junta, the military dictatorship, and the 2008 constitution.’ The military responded heavily with artillery and air attacks and claimed that all camps came under their control on June 27. Sources on the ground though denied that the military had full control over the sites. Sources also said a helicopter was damaged in the fighting, but this remains unconfirmed.

The conflict in Mese Township stands out from other areas of Myanmar due to a notable development: the BGFs switching sides and aligning themselves with the resistance. This event serves a clear indication of the junta’s failure in demobilization, disarmament, and rehabilitation (DDR) policies. The SAC might perceive this event as a warning sign for the need to increase vigilance in monitoring other BGFs and militia forces across the country.

4. Statement of the Three Brotherhood Alliance

The Three Brotherhood Alliance composed of the Arakan Army (AA), Ta’ang (Palaung) National Liberation Army (TNLA), and Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) issued a statement on July 1, saying they will protect international investments in their areas of control and will take action against human trafficking and crimes against international (Chinese) interests. The statement was issued a month after the Chinese-sponsored Mongla meeting between SAC delegates and the three groups.

This statement presumably relates to Chinese interests in Myanmar. China’s special envoy Deng Xijun met with EAOs from Northern Shan State in December 2022 and February 2023 and urged them to ensure stability at the border and to collaborate in cracking down on transnational crime. Chinese Foreign Minister Qin Gang similarly urged the EAOs and relevant stakeholders during his trip to the China-Myanmar border on May 2, to work towards stability at the border and to combat transnational crime.

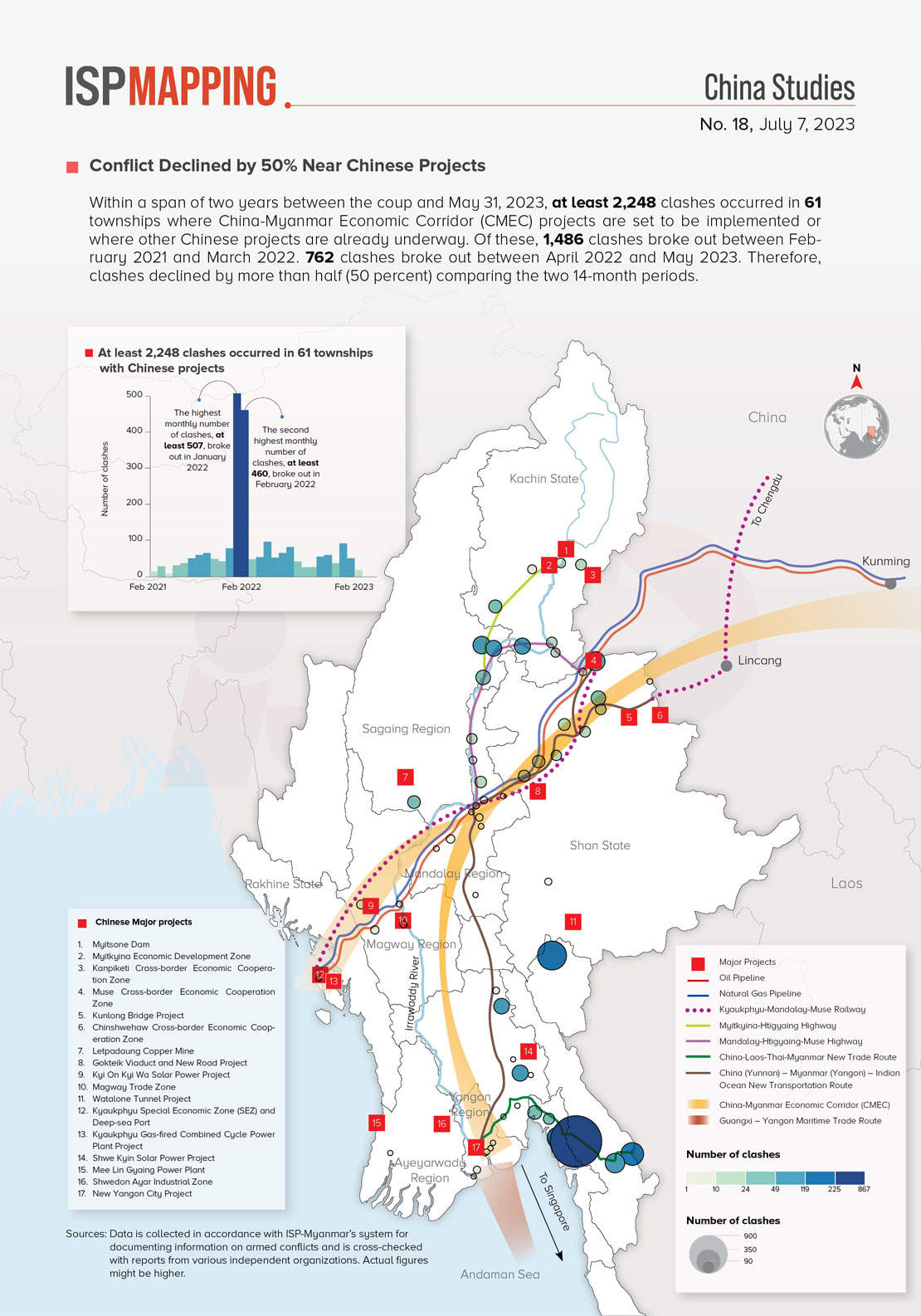

Between May 21-25, People’s Defence Forces (PDFs), the armed wing of the opposition National Unity Government (NUG) have attacked the military posts securing Chinese projects in Kyaukpandaung, and Taung Tha Townships of Mandalay Region, and Salingyi Township of Sagaing Region, at least three times since the Chinese Foreign Minister’s trip.

The recent statement released by the Three Brotherhood Alliance, who maintains close ties with China, appears to align with China’s ‘decoupling strategy’ in the midst of the ongoing conflict in Myanmar. Meanwhile, clashes near Chinese projects in Myanmar have halved nationwide, dropping from at least 1,486 incidents (February 2021 – March 2022) to at least 762 incidents (April 2022 – May 2023). A similar trend can be observed in Shan State, which serves as a junction for the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) and Chinese projects, and where the Three Brotherhood Alliance is based. The number of clashes in Shan State has decreased by half, from at least 154 to at least 77 during the respective periods.

∎ Trends to be watched

Household indebtedness and the microfinance industry in Myanmar

In a tragic development, Pact Global Microfinance Fund (PGMF) (widely known as ‘PACT Myanmar’), which is one of the longest-serving INGOs and the largest microfinance institution, announced it will leave Myanmar on June 26. The PACT Myanmar has been working with USD 360 million in funding, providing loans to around one million rural residents. The immediate impact is significant, resulting in the unfortunate consequence of at least 4,000 staff members becoming unemployed. PACT Myanmar has particularly organized a women’s empowerment program by prioritizing loans to women. The INGO made the statement by forgiving more than US$156 million in outstanding loans to 890,000 borrowers. The main reason for the exit is that INGO cannot comply with the junta’s new registration regulations and also partly due to pressure from its main funder, USAID.

According to a report dated 2019, there were three INGOs, 15 NGOs, 53 foreign companies, 112 local companies, and six joint ventures (in total 189 enterprises) working in the microfinance industry in Myanmar. These agencies have been struggling for returns as many of them encountered huge challenges in loan collections when the Covid-19 pandemic struck. The microfinance industry though remains important, particularly for poverty reduction and living cost support for many urban and rural poor.

The data for Myanmar’s household indebtedness is unknown. According to ‘Myanmar Living Conditions Survey 2017: Socio-Economic Report’ (Published Feb. 2020), conducted by the Finance and Planning Ministry of Myanmar along with international agencies, six out of ten households in Myanmar were indebted, and loans were taken mostly from informal sources. The report did not mention the amount of household debt.

A study by the UN-Habitat, ‘Rapid Assessment of Informal Settlements in Yangon: COVID-19 Pandemic and its Impact on Residents of Informal Settlements’ (May 2020), mentioned households in slums were already heavily indebted prior to the pandemic. Household debt was 555,000.61 Kyats on average. Sixty-one percent of the questioned households had taken above 100,000 Kyats worth of loans within the past 30 days, and 88 percent of the households had taken loans for food. A UNDP report dated earlier, ‘A Regional Perspective on Poverty in Myanmar’ (August 2013), mentioned that in a medium-poor household, the average loan taken was 600,000 Kyats and was mostly used for household consumption. The loan repayments was around 8,000 to 12,000 Kyats per month. Loan sharks and payment problems make it difficult for the poor to ever break free from poverty.

There is much evidence of microfinance supporting poverty reduction in many countries. In neighboring Thailand, the news reported concern about alarming levels of household indebtedness, totalling 15.1 trillion Thai Baht, about 86.9 percent of its GDP. The data for Myanmar’s household indebtedness is unknown and hard to estimate. Stronger SAC control over the industry could result in diminishing resources for the poor, at least in the ability to take temporary loans. It is worth watching the trends of Myanmar household indebtedness, the households’ access to loans, and the progress or regress in the nation’s poverty reduction efforts.

∎ What ISP is reading?

Shan State within the Union of Myanmar

Mong, Sai Kham. (2023). Yangon: Tri Awards Co. Ltd. (in Burmese)

Sai Kham Mong’s book, published in 2023, looks into the intricate history of Shan State. He is an Executive Director of the Shan Studies Center based in Taung-Gyi and a former lecturer at Mandalay and Yangon Universities in first the History Department and later in the International Relations Department. He served as a research fellow at the Chulalongkorn University of Thailand, the National University of Singapore, and the Australian National University.

Focusing on recent Shan State history, the book explores the vast Shan highlands, which are home to diverse ethnic groups with complex historical backgrounds. The author made notable points regarding the occupation of feudal Shan states by the Burmans during the 14th to 16th centuries, and how the British colonization of Burma in November 1885 did not initially aim to conquer Shan State but rather ruled it later as a separate “scheduled area” due to its delayed development. The author also highlights that during 60 years of British rule of Shan State, there was no nationalist attempt to pursue development and freedom for the region strangely.

When the book touches upon the history of Shan state during the independence era, it primarily presents a view aligned with Shan youth who struggled against feudal rule in the Shan State. The book also frequently quotes the writings of Shan politician, U Tun Myint. The book also includes the author’s view on the Union and Panglong agreement, but it does not describe Shan nationalists’ struggle and their history in later years.

The intriguing account within the book focuses on the initiative to teach the Shan language. After the 1962 coup, the Shan Administrative body attempted to begin teaching the Shan language in schools. The main challenge was the argument between using the old script system (round letters) or the new script system (Tiger-head letters, where ‘tiger-head’ refers to the emblem of the Shan State government.) The Shan Administrative body assumed the new system which was invented during the Shan feudal (Chao-Pha) era and the leaders rejected the use of the system. Afterward, it was delayed by several conferences on Shan literature and meetings until 1985. Teaching the Shan language was not implemented until then and the historic cost has been higher for Shan nationals. Quite similar to this Burmese publication, Sai Kham Mong has also published two books in English, ‘Selected Writings of Sai Kham Mong Volume I and II,’ each spanning 404 pages and 284 pages respectively.