Insight Email No. 21

This Insight Email is published on August 22, 2023, as a translation of the original Burmese language version that ISP-Myanmar sent out to the ISP Gabyin members on August 18, 2023.

For this week’s insight email to Gabyin community members, ISP-Myanmar discusses the suffocating lives under military rule. This sense of stagnation stems from the gradual decline of the Myanmar economy, which is now facing not just distress, but a slow demise. We also examine the expansion of conflict as the ongoing Myanmar crisis becomes more brutal and fought more vociferously. Furthermore, there are indications that the SAC could relinquish its responsibility to take up the alternate ASEAN Chairmanship in 2026. Additionally, this bulletin introduces U Ye Htut’s book, ‘Whither to… the Globe and Hlaingtharya?’ published this year. U Ye Htut is a former spokesperson of both the Myanmar government and the former Minister of Information.

∎ Key takeaways

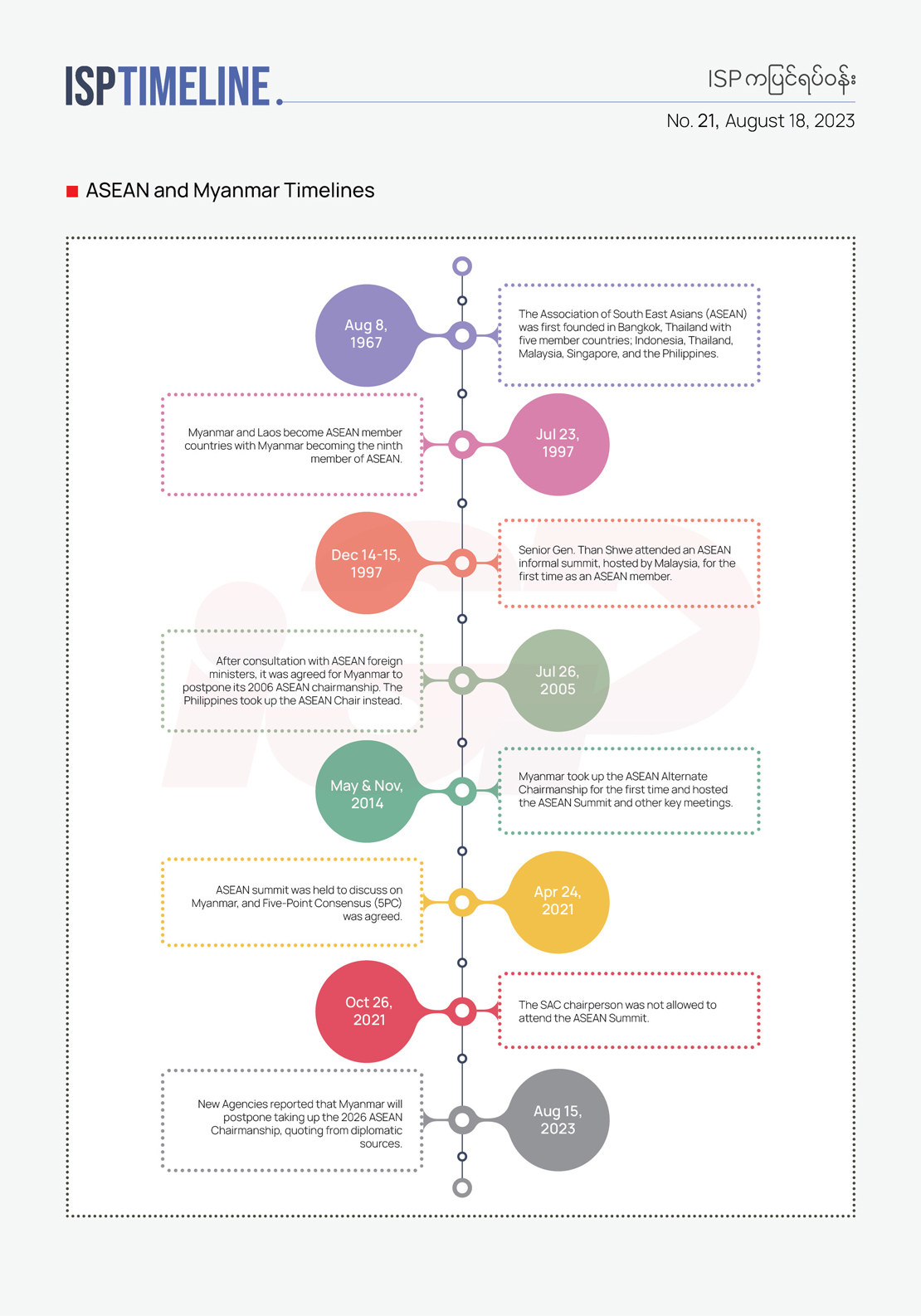

1. Myanmar to shun ASEAN chairmanship in 2026

According to Thailand’s PBS News, Myanmar will defer its ASEAN alternate chairmanship to 2027 instead of the originally scheduled 2026, citing domestic circumstances and unpreparedness as the reasons. The ASEAN chairmanship rotation is based on alphabetical order. Following Indonesia’s (I) chairmanship, Laos (L) is set to assume the role in 2024, followed by Malaysia (MA) in 2025. Myanmar (MY) was initially slated for 2026, but the Philippines (P) will now take its place. This echoes a previous instance when Myanmar’s former junta postponed their ASEAN chairmanship responsibilities in 2006, allowing other ASEAN members to take up the lead. The ASEAN chairmanship was taken only in 2014 when the President Thein Sein’s government came in power with the 2010 general election.

In practice, transferring the ASEAN leadership to other member nations is a complex process that demands extensive consultations. The host country must proactively allocate a budget for organizing events and related expenses. The ASEAN chair is responsible for hosting a minimum of two ASEAN summits, engaging with partner dignitaries, and orchestrating numerous ASEAN ministerial meetings and sessions for officials of various ranks. If Myanmar is unable to assume leadership, the replacement country must make substantial preparations beforehand. In the meantime, leaders of the Myanmar junta are still excluded from attending ASEAN Summit meetings due to their failure to effectively implement the five-point consensus (5PC) aimed at resolving the nation’s crisis.

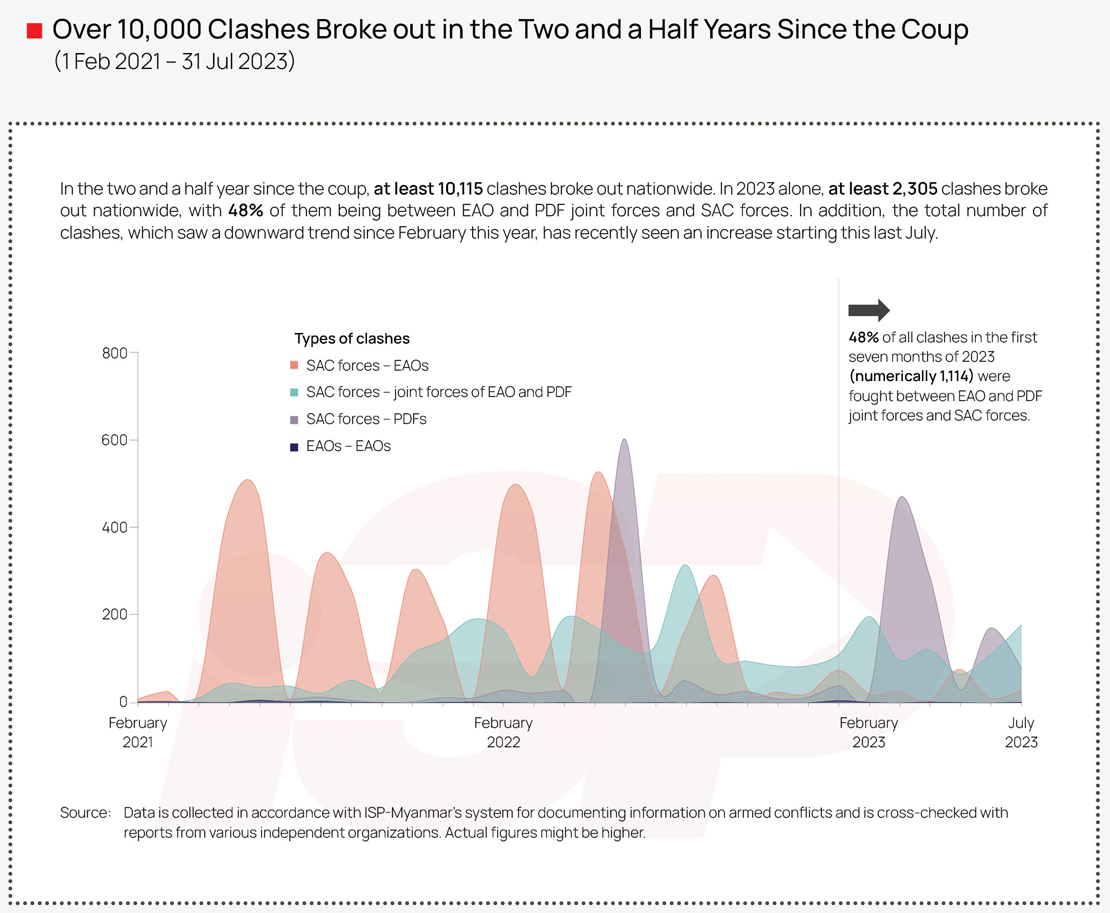

2.Intensifying levels of conflict

Even two years on from the military coup, conflict and civil unrest continue to escalate in Myanmar, with the total number of armed clashes reaching a minimum of 10,000 to July 2023. This figure represents a twofold increase compared to clashes that transpired over the entire preceding decade, spanning from 2010 to 2020 (which numbered at least 4,600). The conflict zones are widely dispersed, encompassing a significant geographical range. Following the coup, skirmishes occurred in at least 139 townships in 2021. This number surged to 193 townships in 2022 and further expanded to 211 townships in 2023. It is noteworthy that while in 2021 and 2022 clashes mostly occurred between the State Administration Council (SAC) and Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs), but that the number of clashes between these two groups decreased in 2023.

Clashes between SAC forces and Peoples Defence Forces, and Local Defence Forces (PDFs/LDFs) under various designations have also been steadily increasing. Besides which, the number of collaborative military operations between EAOs and PDFs has increased. These developments underscore the expanding capacity for force deployment of new forces that have entered the military-political theatre. In August this year, armed conflict reached the center of power, the plains areas surrounding the capital Naypyitaw. The presence and activities of PDFs and allied forces have emerged as substantial challenges to the authority of the junta.

On the other hand, there is a growing debate about whether the Myanmar military is grappling with a waning potency and declining in strength. Nevertheless, the SAC still maintains military advantages, significantly including air superiority, advantages in heavy artillery, and more recently with the deployment of multiple-launch rocket systems. The SAC military command structure remains capable of maneuvering across diverse theaters of conflict and engaging adversaries in various offensives, although their effectiveness has been somewhat diminished. Nonetheless, the ruthless tactics and indiscriminate assaults employed by SAC forces have wrought significant havoc, disproportionately affecting urban and rural inhabitants, particularly in the Karenni, Chin, and Sagaing regions. One significant aspect of the resistance movement is the ad hoc and irregular nature of opposition forces’ movements and engagement. This lack of any apparent cohesive or coordinated strategy means that whatever clashes do occur, are unlikely to result in territorial advances or greater control projection. Civilian casualties though continue to grow country-wide, reaching almost 9,000 civilian deaths in two years (to July 2023). Additionally, instances of home looting and destruction of civilian property are on the ascent, accounting for around 80,000 affected structures (See ISP Data Matters No. 48).

Conversely, the proliferation of diverse opposition armed factions has inherently given rise to intricate political dynamics among combatants, leading to challenges like resource distribution and rivalry for authority. The Defense Minister of the National Unity Government (NUG) recently asserted that the armed resistance could achieve success in the early months of the upcoming year. However, it remains premature to provide a comprehensive analysis at this juncture.

3.Myanmar’s suffocating economy

While the military junta is struggling to maintain control, the foreign exchange value of the Myanmar Kyat is depreciating swiftly. On August 16, one Thai Baht fetched over 100 Kyats while the US dollar is trading at 3,850 Kyats in the informal market. The consequences of the rapidly devaluing Kyat has made imported goods more expensive while domestic commodity prices also rise, placing substantial strain on the populace as they struggle to make ends meet.

The State Administration Council (SAC) is resorting to market price control measures through directives and leveraging threats against export-import traders. In June, the SAC’s Central Bank revoked the licenses of three foreign exchange companies and arrested 51 people working in currency exchange. On July 15, the SAC once again terminated licenses for ten additional foreign exchange companies. More recently, on August 15, an additional 13 foreign exchange companies were compelled to cease operations.

The genesis of these financial problems traces back to the State Administration Council’s (SAC) imposition of foreign currency controls. The banks are compelled to convert all customer accounts denominated in foreign currencies into Myanmar Kyats at predetermined rates. Additionally, a mandate requires foreign exporters to convert 65% of their export income into Kyats within a single day, using the official designated rate, while the remaining 35% of companies’ export earnings are allowed to be converted at the market rate. However, there was a partial easing when, on July 30, the Central Bank shifted the ratio to 50-50. Despite this adjustment, the alteration has not significantly alleviated the competitive constraints faced by traders.

On June 21, the U.S. Government imposed a new round of economic sanctions against two major state-owned banks, Myanmar Foreign Trade Bank (MFTB) and Myanmar Investment and Commerce Bank (MICB). This move had an immediate impact, triggering a decline in the value of the Myanmar Kyat. In a separate development, the SAC announced the forthcoming release of a new limited-circulation currency note with a value of 20,000 Kyats. This has heightened concerns about the Kyat’s stability, eroding people’s confidence in retaining the currency.

In addition, on August 9, Singpore’s United Overseas Bank (UOB) announced its decision to sever correspondent bank relationships with Myanmar, which has worsened confidence in Myanmar’s financial system. The UOB decision complicates the military regime’s access to the global financial system. Furthermore, intensifying armed conflict and natural disasters have damaged crops, properties, and industries, leading to declining productivity. Myanmar’s economic landscape remains fraught with difficulties and uncertainties. The economy isn’t merely grappling with distress—it’s teetering on the brink of collapse. The brunt of these economic hardships is felt most acutely by the marginalized, impoverished, and grassroots segments of the population. They are enduring a gale of difficulty while fighting for survival.

∎ Trends to be watched

Are people happy nowadays?

In a recent episode of the ‘GPS’ program, hosted by Fareed Zakaria, a conversation unfolded with Bruce Feiler, the author of the New York Times bestseller ‘The Search: Finding Meaningful Work in a Post-Career World’. The discourse highlighted widespread discontent among workers with their employment, attributed to various factors such as the pandemic and the subsequent shift to remote work arrangements. However, the situation in Myanmar diverges significantly from global trends, as the populace faces a distinct challenge: the scarcity of viable job opportunities.

According to a recent International Labor Organization (ILO) brief on Myanmar, dated August 2023, the rate of employment terminations increased by 23.5 percent following the military takeover on 1 February 2021. The data includes dismissals of workers increasing by 41 percent while workers’ resignations increased by 22 percent. Many of these ousted workers were from the wholesale and retail trade sector, followed by the textiles, apparel, leather, and related manufacturing sector, and the construction sector. It is significant that among the civil disobedience movement (CDM) many activists refused to collaborate with the regime, which was reflected in the labour statistics. The job termination rate in the public sector increased by 392 percent (comparing the ratio prior to and after the military takeover) following the military takeover, mostly from the education sector. Many dismissals were for ‘non-standard’ reasons and are outside of national labor laws. Such violations rose by 690 percent after the military coup. Their struggle is harsh, some found waged jobs again after termination or become self-employed, but the average time for a worker to return to wage employment was 167 days, ILO reported. It is definitely not a happy experience.

Workers in Myanmar are encountering the most difficult situation. The SAC’s Cooperative and Rural Development Ministry website revealed at least 646 small businesses (SMEs) negated their registrations in the first seven months from early this year to July, as they could not continue their businesses. Simultaneously, a combination of human-caused and natural disasters has inflicted additional devastation upon the population. The situation in conflict-ridden areas has escalated to more dire proportions, with over 1.6 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) navigating treacherous terrains in search of safety. These adversities compound existing economic challenges, further compounding societal distress. The confluence of dim economic prospects, the continuous devaluation of the currency, and the State Administration Council’s (SAC) implementation of ad hoc economic policies has created an unfavorable environment for the creation of new job opportunities. The trajectory of employment dynamics and the voluntary or involuntary termination of jobs is a pivotal concern, as it directly influences the well-being of the majority of citizens.

∎ What ISP is reading?

Whither to… the Globe and Hlaingtharya?

Ye Htut, (April 2023). Whither to… the Globe and Hlaingtharya? Yangon: Ye Htut Publication.

A book authored by a former spokesperson of the Myanmar government and Minister of Information has recently been released. Known for his adeptness in Myanmar prose writing, he has garnered a substantial following through his earlier published essays. This latest publication is an anthology of articles and essays drawn from his Facebook page, encompassing a diverse range of subjects: from personal anecdotes and reflections on pivotal events to intricate portrayals of grassroots communities, travel accounts and his freethought. The book comprises 60 essays in 274 pages.

In the preface of his book, he recited Myanmar’s famous author, Mya Than Tint saying, ‘traveling is a type of politics.’ Against the backdrop of heightened security following the military coup in Myanmar, he documented his experiences and observations from routine local shopping excursions to journeys on the Yangon circular train. His essays maintain a message he wants to convey. As he writes in his book’s preface, ‘At the time of almost diminishing freedom, more vigorous conflicts and antagonisms, it is difficult to write about politics, economics, and social lives. Some ideas can be expressed openly, but some subjects can be only touched finely and left the readers to think further.’ The same paragraph is also printed on the back page of the book.

Within the essays, as outlined by the author, a panorama emerges encapsulating “tantrum situations both in the mountains and on the plains.” These narratives underscore the widespread scarcity afflicting numerous individuals, encompassing persistent and often extended periods of electricity blackouts. Individuals are compelled to navigate these challenges by looking for ways to reduce spending, reducing their food costs, and for those people at the grassroots, to ignore the nutritional value of their foods, embark on troublesome long queues in front of banks and ATMs. Soaring prices change the way people use fuel, and people become disgruntled living lives among the three catastrophes of famine, war, and epidemic disease. There are cases of ‘strangers’ pillaging villages and destroying properties. The reader can see the social-justice sensitiveness of the author through the texts as he recurringly points out the growing inequalities. It is observed that if he has to say something, he regularly stands with the view of the grassroots people.