Insight Email No. 26

This Insight Email is published on October 30, 2023, as a translation of the original Burmese language version that ISP-Myanmar sent out to the ISP Gabyin members on October 27, 2023.

This week, ISP-Myanmar’s Insight Email focuses on three main topics: first, the resurgence of war in Northern Shan State, including in the Palaung area, second, the unproductive peace overture of the SAC chief, and third, the possible trend of humanitarian aid to Myanmar conflict-affected population in a new form. In addition, the bulletin reports a spread of pinkeye infections in Myanmar, where the population is struggling under a frail health care system. Contrarily, Myanmar fans have spent large amounts of US dollars to vote for a candidate for the Miss Grand International pageant while many are stressed from hunger, war, and scarcity. This could be fulfilling a psychological need of the Myanmar population: their hunger for a shared and collective pride in their society. Last, but not least, this bulletin briefly introduces a report on the Rohingya youth, a situation encountered in the Bangladeshi camps.

∎ Key takeaways

1.A Flare-Up of War in Northern Shan State

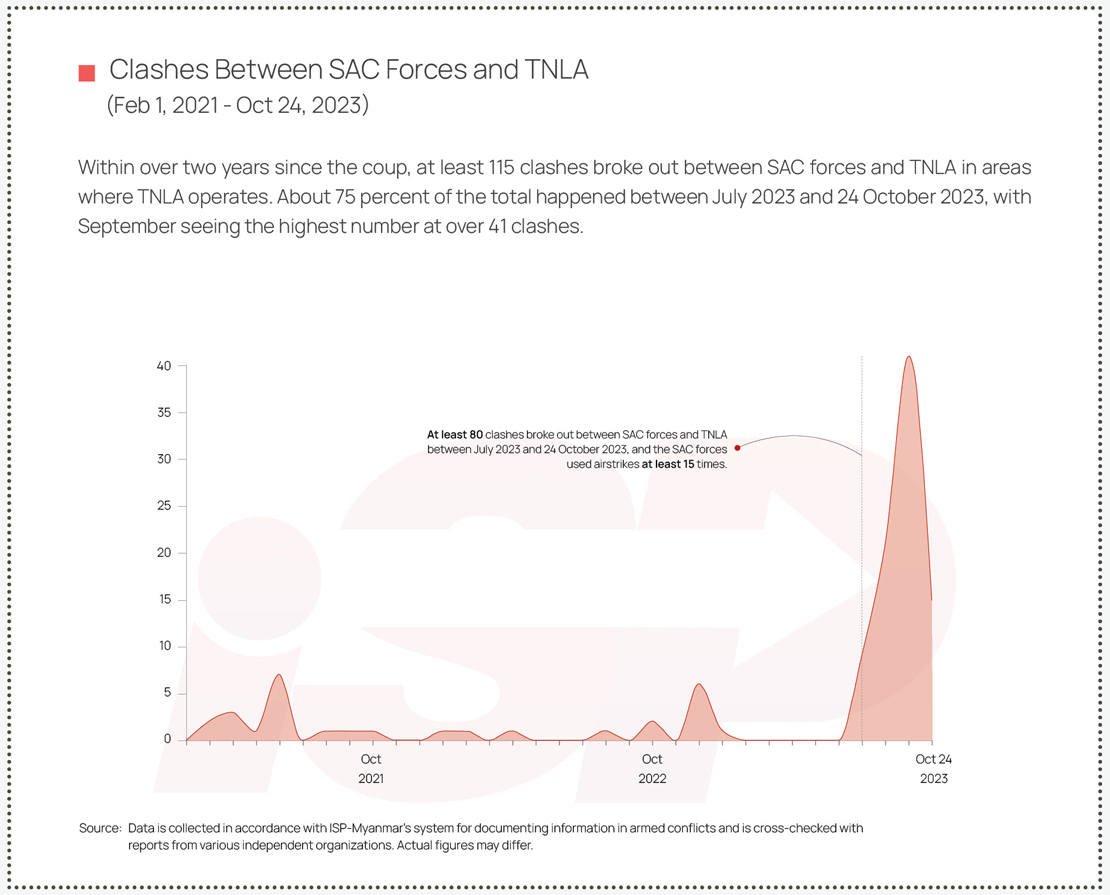

There has been a flare-up of fighting intensifying in the Northern Shan State for four months; unlike that seen in previous years. Fighting has been sporadic in the area since the 2021 military coup. Three groups of the Northern Brotherhood Alliance in northern Shan State have recently launched Operation 1027, and there is now a clear resurgence of war in the area. In this bulletin, we will examine the fighting between the State Administration Council’s (SAC) forces and the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA). Soon after the unproductive Mongla peace talks between the Three Northern Brotherhood groups and the SAC peace team in June 2023, the junta forces damaged Palaung national flags hoisted in five villages of Lashio Township and road signs described in the Palaung language. The forces warned the villagers not to re-erect them without permission.

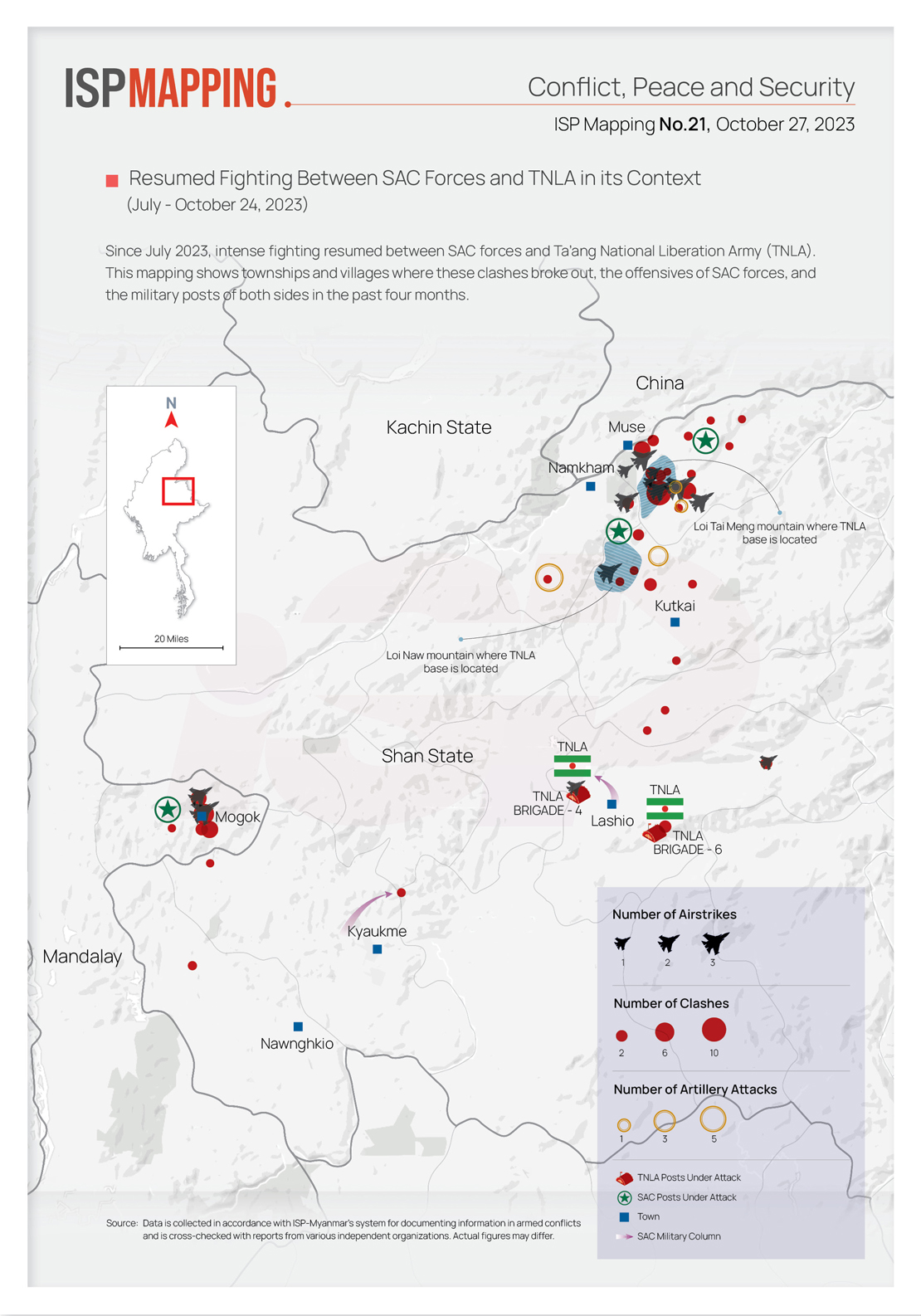

In July, junta forces initiated attacks against TNLA forces in the Kyaukme and Muse townships of Shan State, where the TNLA has been expanding its administration. In Kutkai and Lashio Townships, the junta forces shelled and bombed from the air to the civilian living areas without apparent fighting with the TNLA. The air force attacked the living quarters of Sai Khaung village of Muse Township on July 24 and bombed a TNLA camp close to Einai village of Lashio Township on July 27 with Mi-35 attack helicopters. Mai Aik Kyaw, TNLA’s spokesman, said that he is not sure what the military objectives of the junta are, but that an offensive against the TNLA has been initiated since July of this year.

The most intense fighting occurred around the Sei Lant and Kho Mone villages of Muse Township, where the TNLA has kept some of its camps in a strategic position on the China–Myanmar trade route. On August 28, the junta forces mounted an offensive against the TNLA camp near Kho Mone village with its three infantry battalions in cooperation with three groups of local militias, along with artillery support. The SAC forces simultaneously shelled around Sei Lant village. Kho Mone is situated just one and a half kilometers from the Chinese border and Sei Lant is rather a populous village, situated on the route connecting Muse and the Manhero border checkpoint. The SAC jet fighters bombed Sei Lant village on August 29 and fired more than 30 rounds of shells, and 2,200 villagers were reportedly displaced from their homes. Since the military coup, the TNLA has expanded and strengthened its administration in these places.

According to ISP-Myanmar data, from July 11 to October 24, at least 80 clashes occurred between the SAC forces and the TNLA in Muse, Lashio, Kuikai, Kyaukme townships of Shan State and Mogok Township of Mandalay Region, including at least fifteen air attacks. The junta air force has mounted at least 40 attacks, including bombing with lethal 500-pound bombs. The TNLA stated in a press release that the junta has shelled more than 400 times.

Observers speculate that the attacks against the TNLA could be because of the TNLA’s secret support for anti-junta forces, the People’s Defense Forces (PDFs), because it has been supplying weapons to them, and because it failed to respond to the SAC’s several calls for peace talks. With Chinese mediation, the Northern Brotherhood Alliance, including the TNLA, met with the SAC’s peace delegation in June at Mongla, but without apparent success.

The International Crisis Group (ICG) recently published an analysis on the TNLA on September 4 with the title, “Treading a Rocky Path: The Ta’ang Army Expands in Myanmar’s Shan State.” The report described that the TNLA became one of the country’s most powerful ethnic armed groups by strengthening its control over a swathe of territory in northern Shan State. The group has gained territory and recruits and expanded the administrative structure in parallel. The rise of the TNLA has provoked conflict with both other ethnic armed groups and the military. The ICG recommended that the TNLA “refrain from further expansion, which would risk renewed conflict, and take greater care to avoid provoking” and “provide more services to civilians, but it would also afford them a degree of moderating influence over the leadership of armed groups.”

The SAC is concurrently engaging in war on all fronts with the TNLA, the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), and the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) in the northern parts of Shan and Kachin states. On the morning of October 27, three Northern Brotherhood Alliance forces—the MNDAA, TNLA, and AA—jointly launched simultaneous attacks on Laukkai, Chinshwehaw, Lashio, Kutkai, Muse, and Namkham townships, under the name of Operation 1027. They stated that the military operation intends to destroy the junta, its allied militias, and online scam businesses in the areas. But it is hard to speculate about the results of this operation.

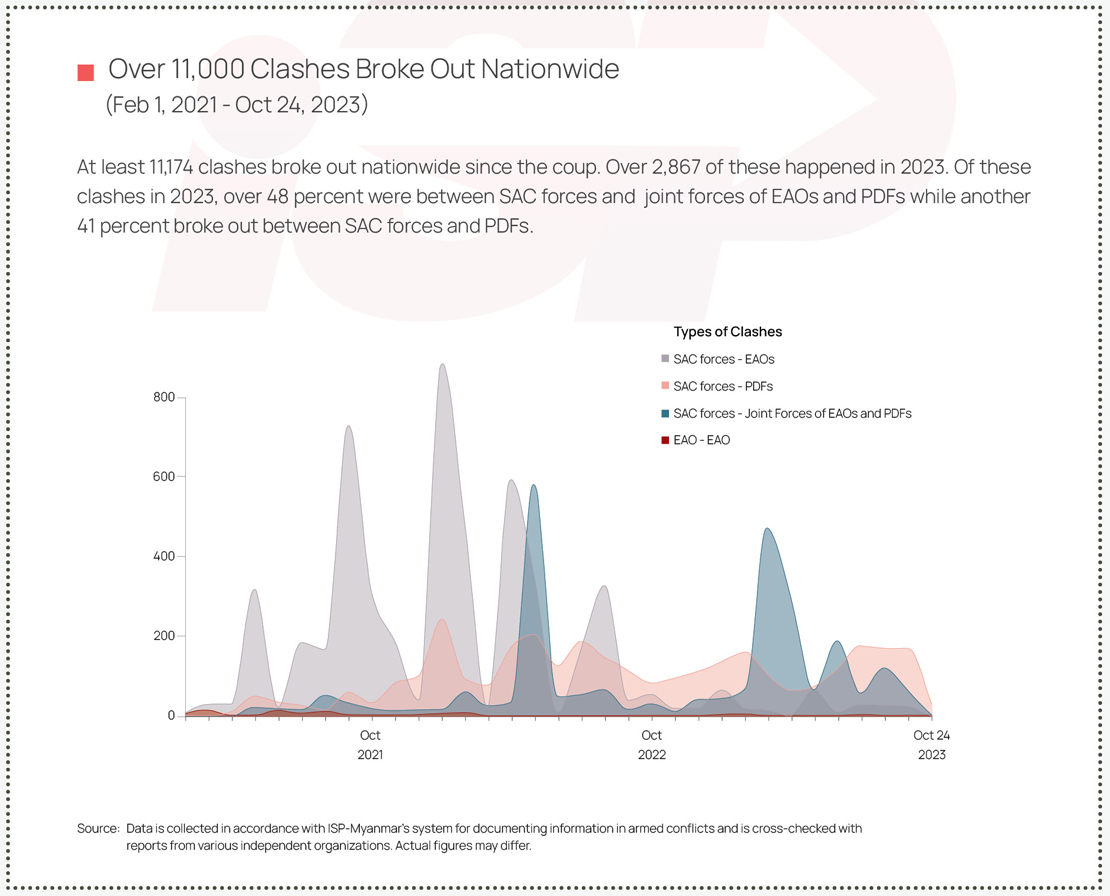

Along with the flare-up of war in northern Shan State, fighting is occurring in Karen and Mon states and in Bago and Tanintharyi regions between the junta’s forces and resistant Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), People’s Defense Forces (PDF), and local defense forces. Moreover, the military tension between the junta’s forces and the opposition forces in Kayah and Chin states and Sagaing and Magwe regions is neither diminishing. Apart from Yangon and Naypyitaw, the military engagements have ostensibly and gradually escalated in other areas of the country since the coup.

2.The Pinkeye Epidemic in Myanmar

Myanmar netizens commonly share photos of their infected eyes on social media, mentioning an epidemic in schools. Yet no official caution or report has been issued by SAC newspapers or the Health Ministry.

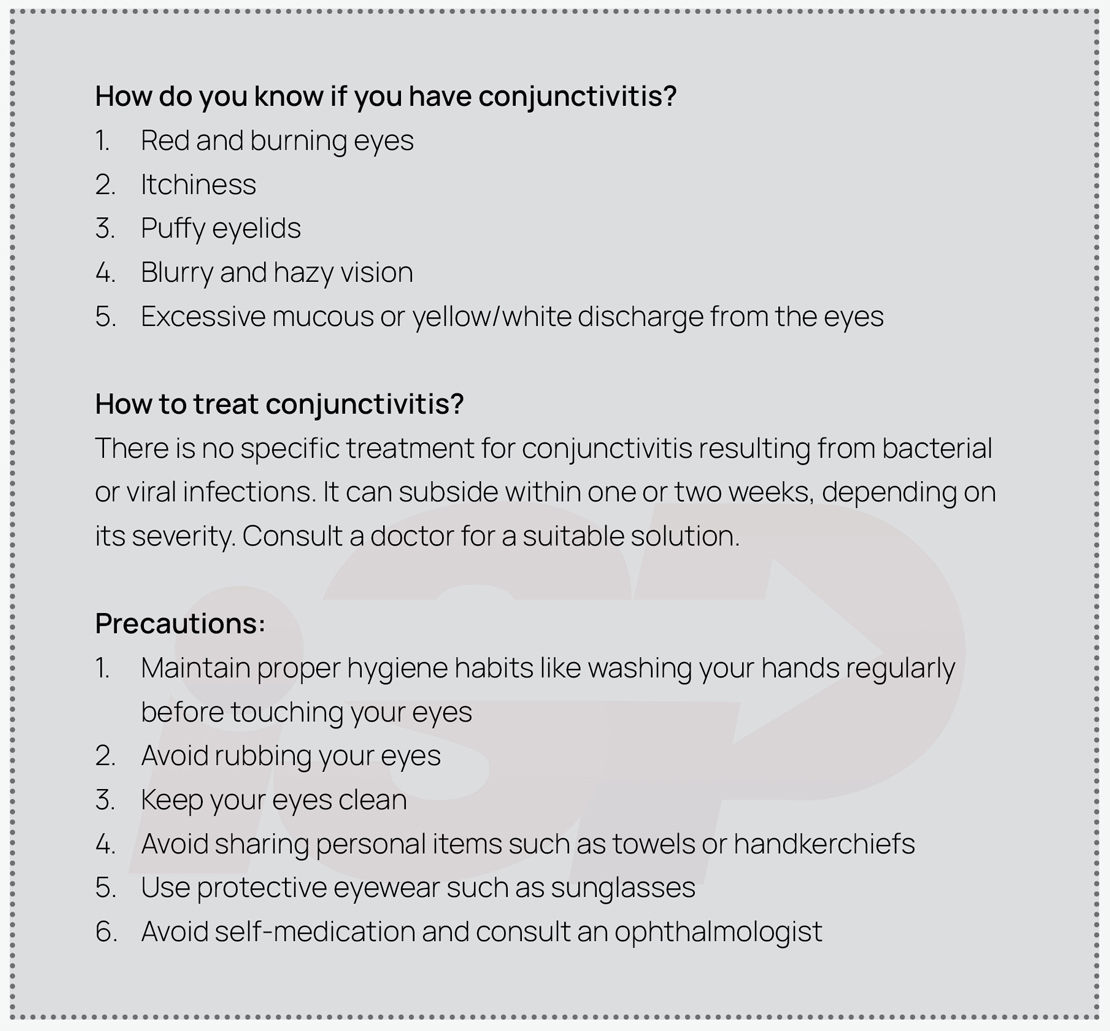

Regional news has reported that an epidemic of eye sores has rapidly spreading in some Asian countries after the summer heatwaves and record rainfall. Medical doctors explain it is conjunctivitis caused either by bacteria or viral infection. The blood vessels in the eyelid and eyeball (in the conjunctiva) are inflamed; the condition is called “‘pinkeye,” due to the appearance of a reddish or pink color in the eye. In severe cases, it is called “red eye.” In most cases, bacterial infection can be identified by a sticky, gooey, yellow or white discharge. Viral infections caused by adenoviruses rarely exhibit this discharge and so this eye discharge indicates the presence of bacterial infection.

This eye infection is preventable and is mostly spreading because people are rubbing their eyes with their own hands. According to infected patients, within a few hours, their eyes become swollen and they are lethargic with fever and cold symptoms. Sometimes, they feel photophobia. There is no cure for the viral infection and the symptoms may subside within one to two weeks. (Health Departments warn sometimes that symptoms may take up to 30 days to disappear.)

Local news in India, Vietnam, and Pakistan reported that the epidemic is occurring in their countries. According to a report on September 28, around 400,000 people were infected in Pakistan and authorities were forced to shut down 56,000 public schools and thousands of private schools. There were widespread infections in Singapore in February and March of this year. In Vietnam, from January to September, 63,000 people were infected with pinkeye. According to a report on September 6, some areas of India, close to Myanmar, such as Arunachal Pradesh and Nagaland, had experienced a pinkeye epidemic and were forced to close some schools. The Indian Health Department data recorded more than 38,000 people infected in some states.

No special preparations or action by the SAC Health Department had been reported regarding the recent pinkeye infection. The public health care system in Myanmar is obviously weak and has further deteriorated under the pandemic, the military coup, and the resulting civil disobedience movement (CDM) of health workers. Myanmar citizens have to come up with their own solutions to tackle their health problems, large and small—from child vaccinations to serious illnesses. The SAC has recently tried to impose taxes on the informal income of health workers from their work outside of public hospitals. But it has nothing to do with developing quality health care. President U Htin Kyaw of the National League for Democracy (NLD) administration promised to work for a system of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) in Myanmar by 2030 in a conference held in Japan in 2017. But this promise could easily be forgotten or ignored.

3.SAC Chairman’s Peace Overture

Recently, the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) marked its eighth anniversary and the SAC intended to celebrate differently, but this did not happen successfully. Not all invited ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) attended the event. Particularly, former President Thein Sein, who presided over the NCA, was not present at the event; non-signatories of the NCA and members of the Federal Political Negotiation Consultative Council (FPNCC) also did not attend. Previously, the NCA events were organized in ‘joint ownership’ in cooperation with the government, parliament (Hluttaw), and EAOs, each with an equal share in detailed decision-making. The last NCA event lacked this joint spirit of cooperation and there were many errors in the seating plan and protocols of the event, analysts said.

The most depressing act or the occasion was Snr. Gen. Min Aung Hlaing’s speech. He stated that the Tatmadaw (the country’s defense forces) is still holding its six principles for peace. But he provided no new offer to the EAOs to de-escalate the conflict. Before this, EAOs and political groups thought that the NCA talks could be an alternative way to revise the unpopular 2008 constitution, but based on his speech, this option is not viable anymore. Instead, he invited EAOs to cooperate under the 2008 constitution. He lectured a lot on history, but it was his version of history. He mentioned that the ‘Union’ has existed in Myanmar since feudal times. He proposed controversial ‘region-based’ federalism without any prior consultation with ethnic groups. (However, in his fourth speech at the anniversary of the NCA, in 2019, he also stated that Myanmar could be rather a parallel to India’s model of federalism.)

Although the SAC has stated in its five-point roadmap that “an emphasis will be placed on achieving enduring peace for the entire nation in line with the agreements set out in the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement,” the records show that air attacks, artillery shellings and cases of arson and pillaging are escalating and that the conflict is intensifying. Min Aung Hlaing particularly tried to make a difference during his reign, but without achieving outstanding success. For example, on the occasion of the Diamond Jubilee of Myanmar’s Independence Day, he honored several people who had performed for the country for decades and attempted to build national unity, but it was a lackluster event with nothing remarkable.

Then, Min Aung Hlaing announced invitations to meet EAO leaders personally without conditions on April 22, 2022. They could make demands to him personally and the meetings would make them more understanding. But no spectacular results were made except for a few meetings with EAO leaders, including non-signatories of the NCA, the northern EAOs. The SAC leader has reportedly planned to hold a peace conference before the end of 2023 as a next step. The SAC also announced “2022 as a year of peace.” It is worth waiting to see whether or not the peace conference materializes. The basic reason is that although the SAC invited and discussed the issues with the EAOs on previously agreed Union Accords and other issues related to federalism and future Union formation, the SAC generals keep the stern position that this must be done under the 2008 constitutional framework. Like the military’s nature, the peace team of the SAC has to wait for directives from their superiors and lacks the ability to strike new bargains with their dialogue partners.

According to the SAC, from February 2021 to September 2023, they held 73 meetings with NCA signatories, 25 meetings with non-signatory EAOs, 16 meetings with political parties, and seven meetings with peace negotiators; in total, there were 121 meetings. To build peace, the military declared a unilateral ceasefire from December 21, 2018, until December 31 of this year.

According to inside sources, the SAC is presently forming several channels to deal with the EAOs for fostering peace as committees, groups, and agencies, but these groups are competing with each other and fail to cooperate among themselves. Some generals are included in several teams, but it is unclear who will be the highest decision-making body. Meanwhile, EAO leaders asked for a one-stop service to talk to the junta and for them not to frequently change their dialogue partners.

The chief of the SAC peace team, Lt. Gen. Yar Pyae, was recently promoted to a member of the SAC and Home Minister; he has also been occupied with other important tasks. Since then, the Secretary of the SAC National Solidarity and Peacemaking Negotiation Committee (NSPNC), Lt. Gen. Min Naing (OTS-66 graduate), has emerged as a major mover. He was the best cadet in OTS-66, analysts believe he is a results-oriented implementor who seems active and willing to take the initiative.

After the official eighth anniversary NCA ceremony, a review workshop was held with several key stakeholders. Among the final 18-point recommendations, the meeting acknowledged the role of independent mediators and sought to foster humanitarian assistance to the conflict-affected peoples. Though some EAO delegates proposed to release political prisoners on good will, this was not realized.

4.Beauty and the Beast

Miss Myanmar, Ms. Ni Ni Lin Eain, was named the First Runner-Up and won the Popular Vote and Country’s Power award in the Miss Grand International 2023 contest held in Ho Chi Min City, Vietnam, on October 25. The latter two awards are chosen by two ways: people voted for their favorite candidate through Instagram and by buying credit, a unit equivalent to one USD. Myanmar’s people eagerly voted for Ms. Ni and reportedly she earned 2.3 million votes on Instagram which earned her the Country’s Power award. In the credit voting category, she earned 34 per cent of the total votes.

Many netizens have criticized people senselessly voting for a beauty queen on social media during a time of conflict, poverty, and scarcity in the country. Myanmar, a country plagued by civil strife and underdevelopment, has a population which seems ravenous for shared and collective pride, and this could be a good explanation for the voting. It is similar to Myanmar’s people enthusiastically supporting the martial arts fighter Aung La Nsang, the badminton champion Thet Htar Thuzar, and the Myanmar Sepak Takraw team, which recently won gold in the nineteenth Asia Games in China.

∎ Trends to be watched

Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) and a New Humanitarian Initiative

Since the military coup in 2021, civil conflict has escalated and expanded and new actors have joined the country’s civil war. As a dire consequence, the civil war devoured tremendous human and infrastructural costs. Along with intensifying climate crises, Myanmar has experienced rising humanitarian needs. But the junta’s own restrictions on international agencies and international sanctions, along with the current conflict, make it impossible to attract large-scale humanitarian aid to Myanmar.

Immediately after the military coup, there were several suggestions for Myanmar talked about noisily, including the responsibility to protect (R2P), a no-fly-zone, safe havens, arms embargoes, a humanitarian corridor, etc., but none of these materialized. Neither innovative ideas for humanitarian assistance to the neediest nor existing mechanisms worked in Myanmar. For example, the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) has prescribed clauses in detail for civilian protection from conflict as well as conditions for providing humanitarian assistance. For the moment, along with the eighth anniversary of the NCA commemoration, the side workshop discussed the reorientation of such subjects.

Meanwhile, the National Unity Consultative Council (NUCC) organized an “Inclusive Humanitarian Conference (2023)” in September and issued an advocacy paper. The statement acknowledged the humanitarian crisis that Myanmar is suffering from and how urgent it is to act. At the conclusion of the conference, it was suggested that the international community should not kneel to the threat of the SAC’s pressure. Instead, humanitarian assistance should be provided to the ethnic-controlled areas and through seasoned community-based organizations (CBOs) and civil society organizations (CSOs). The call is parallel to the localization approach. 1

Nevertheless, humanitarian assistance in Myanmar can hardly be free from politicization, since the regime has been restricting all forms of aid due to security concerns and the opposition groups insist that working with the regime on humanitarian grounds could result in offering the junta legitimacy. They said the SAC forces have been practicing a “four cuts” strategy intentionally, by setting fire to towns and villages and pillaging civilian property, which is driving the population into humanitarian crisis. 2

The politicization of aid is conducted by all sides, all the time. The approach of localization and providing humanitarian aid through civil society organizations (CSOs) is consensual and is presently working. However, such aid is limited from reaching broader beneficiaries.

Meanwhile, some agencies seek alternative approaches for humanitarian aid in Myanmar to revitalize the peace process. In August, UN Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, Martin Griffiths, visited Naypyitaw and met with Min Aung Hlaing, despite the fact that many opposed his trip as lending legitimacy to the junta. In a statement about his trip, he noted that “successive crises had left a third of Myanmar’s population in need of aid” and appealed for funding for the 1.9 million IDPs in Myanmar. He also called for “expanded humanitarian access and increased funding to assist the 18 million people in need of aid across Myanmar.”

Yet only a trivial flow of humanitarian assistance is now being provided by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), despite difficult mechanisms and restrictions. The Technical Support Centre (TSC), working under the Joint Monitoring Committee (JMC) mechanism, has prepared a proposal and negotiated with regional military commanders to obtain permission to receive aid. On the other side, Humanitarian Dialogue (HD) group discussed with the relevant EAOs. After that, some flow of humanitarian assistance were provided to the IDPs seeking refuge in Karen State’s Lay Kay Kaw, Leiktho and Yardo townships, Shan State’s Taunggyi, Hsihseng and Yaunghwe (Nyaungshwe) townships, and in Rakhine State—they amount to approximately 90,000 IDPs in total. Japan’s Nippon Foundation has been assisting displaced persons in Rakhine State. However, their support is insignificant compared to the total 1.9 million IDPs recognized by UN OCHA. A UN Humanitarian update on October 2 estimated that the humanitarian response plan and Cyclone Mocha flash appeal remain critically underfunded; these plans were estimated to have a combined cost of US$887 million and only 28 percent of the required funding has been received.

Seemingly, the narrow entry to the humanitarian assistance door may be intended to mitigate conflict-inflicted destruction and to promote the protection of civilians. Switzerland and Finland have been interested in doing this. Norway may follow this approach, since the Norwegian diplomat responsible for peace and reconciliation, Ms. Mariann Ruud Hagen, arrived in Naypyitaw recently. She will meet with the SAC leaders, leaders of the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), and peaceniks in the previous governments. This is a trend regarding Myanmar’s peace and conflict that deserves to be closely followed.

1. Global Mentoring Initiative & RAFT Myanmar. (May 2012). Localization in Myanmar: Supporting and Reinforcing Myanmar Actors Today and Tomorrow. HARP-F and Crown Agents. Retrieved online at https://reliefweb.int/report/myanmar/localisation-myanmar-supporting-and-reinforcing-myanmar-actors-enmy

2. Decorbert, Anne. (2016). The Politics of Aid to Burma: A Humanitarian Struggle on the Thai-Burmese Border. Routledge Contemporary Southeast Asia Series.

∎ What ISP is reading?

Youth Congress Rohingya (September 2023). “This Persecution

is The Worst There is: Restrictions on Rohingya Freedom of

Movement in Bangladesh.” 88 Pages.

In September 2023, Youth Congress Rohingya (YCR) published survey findings, in coincidence with Myanmar SAC’s launch of a Rohingya refugee repatriation pilot project. (Note: Myanmar’s successive governments don’t use the term “Rohingya,” but call these people Bengalis.) In May of this year, the Myanmar regime allowed 20 representatives out of the 1.2 million Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, as a short-term visit for confidence building. Moreover, the regime invited international diplomats to the areas to observe the preparations for the return of the refugees. But UN Special Rapporteur Tom Andrews and some activists, along with some INGOs, have insisted on immediately suspending a hasty pilot repatriation project for the Rohingya to return to Myanmar, where they face serious risks to their lives and liberty. Bangladesh’s junior minister from the Foreign Affairs Ministry, Shahriar Alam, assured the reporters in June that the Rohingya “are going there voluntarily… and if they feel uncomfortable, there is a chance to bring them back. In that case, we see no argument to go against it.”

This report attempted to portray the real life in Rohingya refugee camps by collecting answers from the refugees. The ISP cannot make sure who makes up the YCR, but they are seemingly residents of the camps who want to make change. The report starts with a story of the 45-year-old female, Samira, whose husband was killed during the mass riots. She fled to the refugee camp in Bangladesh just to survive. She sent her 16-year-old son to study at an Arabic school. Then, she fell seriously ill in January 2023 and asked her son to return to meet her. Her son was stopped at the gate of Camp 8W because he was wearing a Kurta, a loose collarless shirt worn by Islamic scholars. Her son explained to the guard, a Bangladeshi policeman, where they were living and the reason for meeting his sick mother. The police accused him of being a drug dealer, tortured him and didn’t allow him to enter. The police confiscated his money, around 3,000 taka (approx. 28 USD). He pleaded with them not to. He was held at gunpoint and beaten until he fell to the ground. Finally, the section head asked for his pardon and he was released, but the police didn’t return his possessions. When his mom heard what was happening, she had a heart attack, as she could not bear the suffering. She said “this persecution is the worst there is,” which is the phrase used as the title of the report.

The YCR survey was conducted with respondents living in Rohingya refugee camps. The YCR also interviewed the Bangladeshi police to confirm some of the events and procedures. According to the findings, 99 percent of the respondents said there are restrictions on freedom of movement within the camps, and 94 percent reported that these restrictions impact their daily lives. Even the movement of refugees between the camps requires the permission of the authorities and curfews are imposed on the camps. The Rohingya are restricted from assembling and owning smartphones or laptops. Sixty-two percent of respondents reported that they had personally experienced punishment related to movement, and 96 percent reported that the Armed Police Battalion (APBn), who are guarding the camps, were those that carried it out. They also experienced violence and forced labor. Ninety-seven and one-half percent of survey respondents reported experience or knowledge of corruption in the camp security forces regarding the smuggling of goods, and for travel in and out of the camps. The majority of respondents believed that these police have imposed the most severe restrictions intentionally, as the Bangladeshi government intends to coercive them to relocate to the undesirable Bhasan Char Island Camp or to return to Myanmar. Respondents have evaluated their current situation in Bangladeshi camps on violence and discrimination by APBn as similar to their experiences in Myanmar before the 2017 community riots, but 65 percent believe the restrictions in Bangladesh are worse than those of Myanmar.

To receive ISP Insight Emails in your inbox, subscribe at this link.