Insight Email No. 29

This Insight Email is published on December 18, 2023, as a translation of the original Burmese language version that ISP-Myanmar sent out to the ISP Gabyin members on December 15, 2023.

Many economies of the world have recovered from their economic recession due to the Covid-19 pandemic, but Myanmar is an exception. By the accumulating adverse effects of the military coup in 2021, Myanmar remains the only economy in East Asia that has not yet returned to pre-pandemic levels of economic activity. This week’s ISP Insight Email No. 29 discusses Myanmar’s sustained economic decline, the development of the ethnic Chinland Council and its repercussions, and the shift in the fuel policy and the questionable accountability of the junta leadership for its later consequences. Again, the bulletin briefly recalls the three OnPoint analyses published by ISP-Myanmar, and introduces Enze Han’s book Asymme-trical Neighbors: Borderland State Building Between China and Southeast Asia, which explains the effects of living beside a superpower neighbor for a nation.

∎ Key takeaways

1.A Sustained Economic Decline in Myanmar

Myanmar’s economic growth is discouraging, as the country is experiencing a sustained decline. The World Bank’s Myanmar Economic Monitor, published on December 12, 2023, reported that “growth is expected to remain subdued over the rest of 2024 and into 2025 given a broad-based slowdown across productive sectors including agriculture, manufacturing, and trade”. The World Bank report, entitled ‘Challenges Amid Conflict’ projected that Myanmar’s economy would grow just one per cent during the year to March 2024, leaving it the only economy in East Asia that has not returned to pre-pandemic levels of economic activity. The World Bank warns that the economy will continue to slump over the rest of 2024 and into 2025, given a broad-based slowdown across productive sectors.

The World Bank report also pointed out the rapid rise of consumer prices and depreciation of the country’s currency, while the Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EIU) December 13 analysis reported that because of the de facto devaluation in Myanmar’s exchange rate regime, there will be significant pressure on the official exchange rate and the parallel market rate. The EIU reported that Myanmar kyat market rate has fallen by more than 60 per cent since the 2021 coup. Moreover, the World Bank reported pressure against production in Myanmar due to “conflict, high logistics costs, trade and foreign exchange restrictions, and electricity disruptions,” which have raised the cost of doing business. Indicators of business activity have worsened since mid-2023, reported the Myanmar Economic Monitor, as firms reported operating at just 56 per cent of their capacity in September, down 16 percentage points from March.

The World Bank reported, based on the International Food Policy Research Institute’s (IFPRI) survey conducted in mid-2023, that measures of food insecurity have also worsened, since 40 per cent of households reported earning less than in the previous year. The World Bank’s Country Director for Myanmar, Cambodia, and the Lao PDR advised that “the economic situation has deteriorated, and uncertainty about the future is increasing… and high food price inflation has had a particularly severe impact on the poor.”

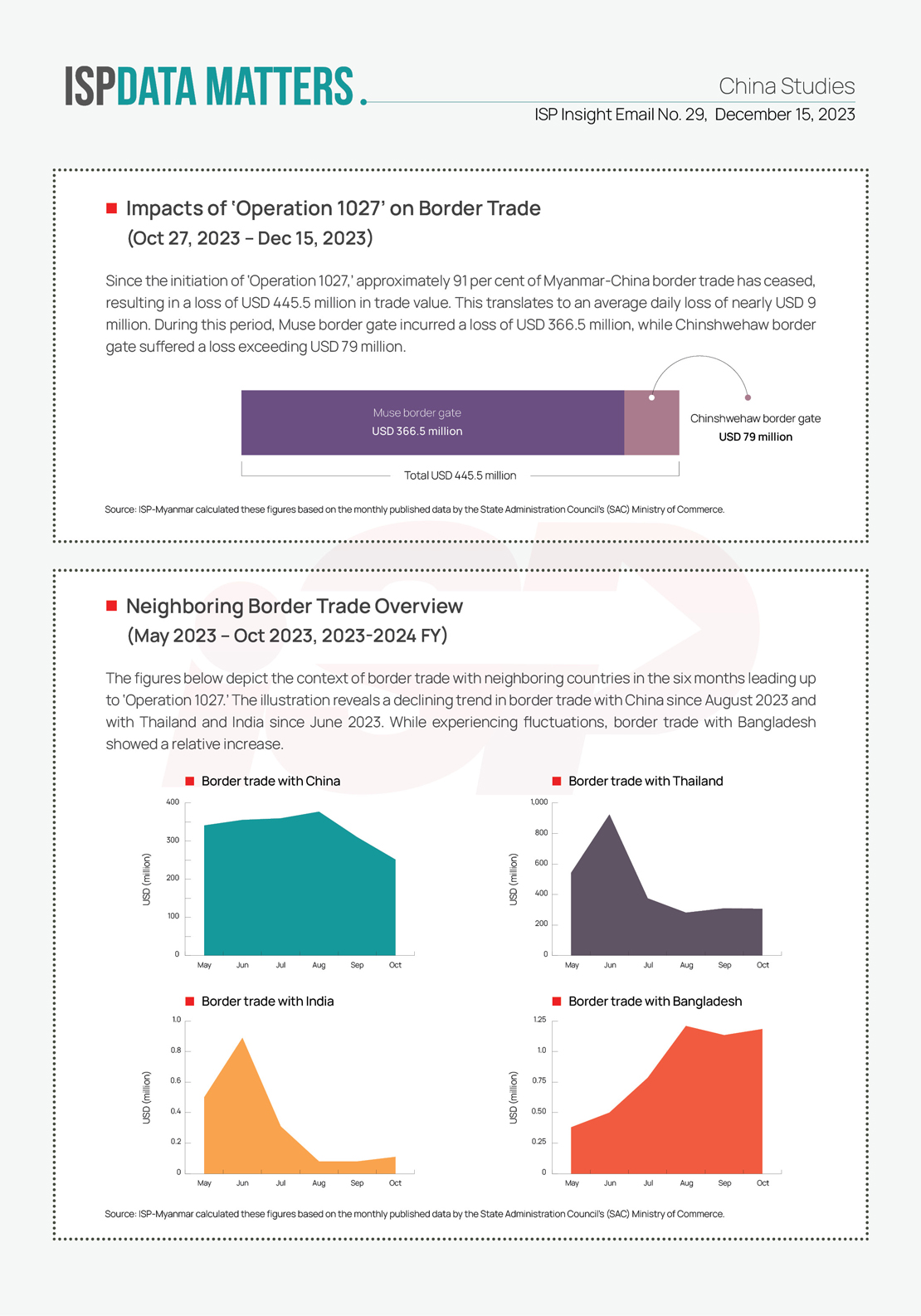

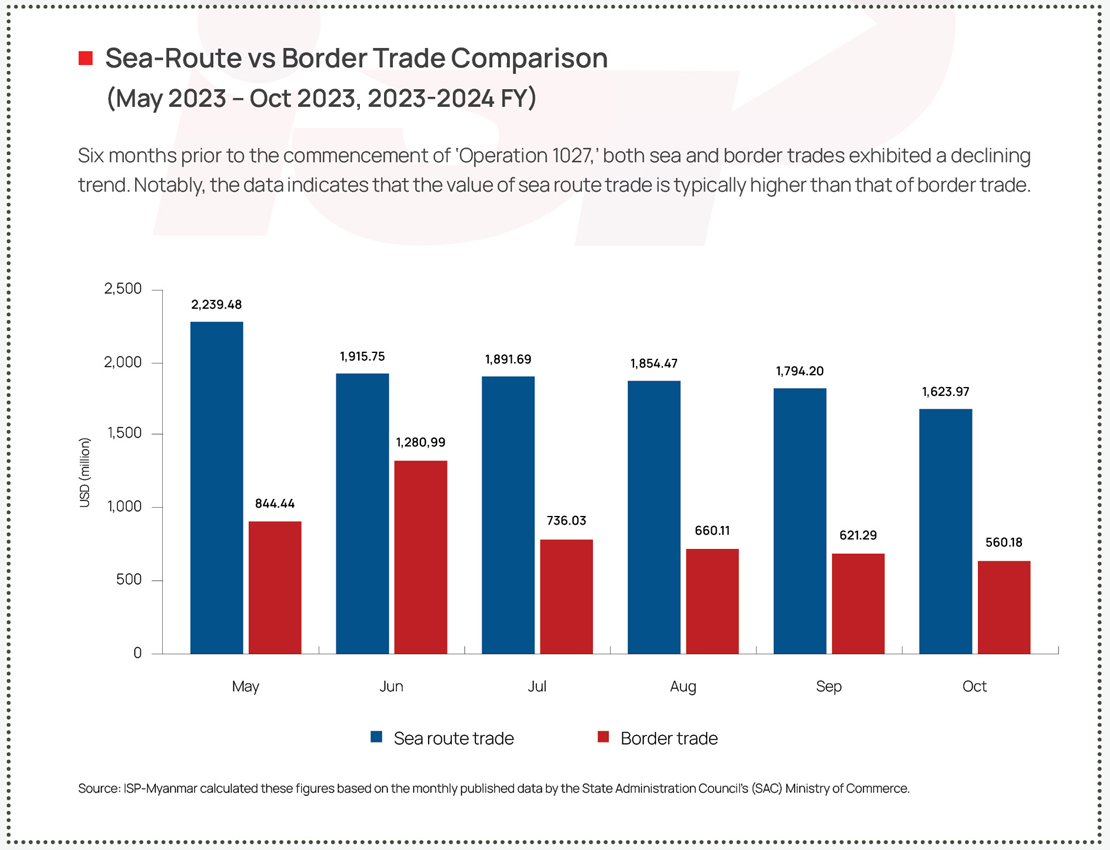

According to ISP-Myanmar’s socio-economic study conducted to understand the post-coup situation of Myanmar’s society, the rising commodity prices are one of the most prevalent problems people encounter in their daily lives. Along with these economic hardships, frequent electricity blackouts and losses of job opportunities are increasing the burden on them (see ISP Insight Email No. 28). According to ISP-Myanmar’s data, since the armed conflict has intensified and broadened, it is imposing more pressure against logistic flows, and leading to severe impacts on economic activities. For instance, ‘Operation 1027,’ launched by the Three Brotherhoods Alliance (3BHA) on October 27, has effectively choked border trade with China.

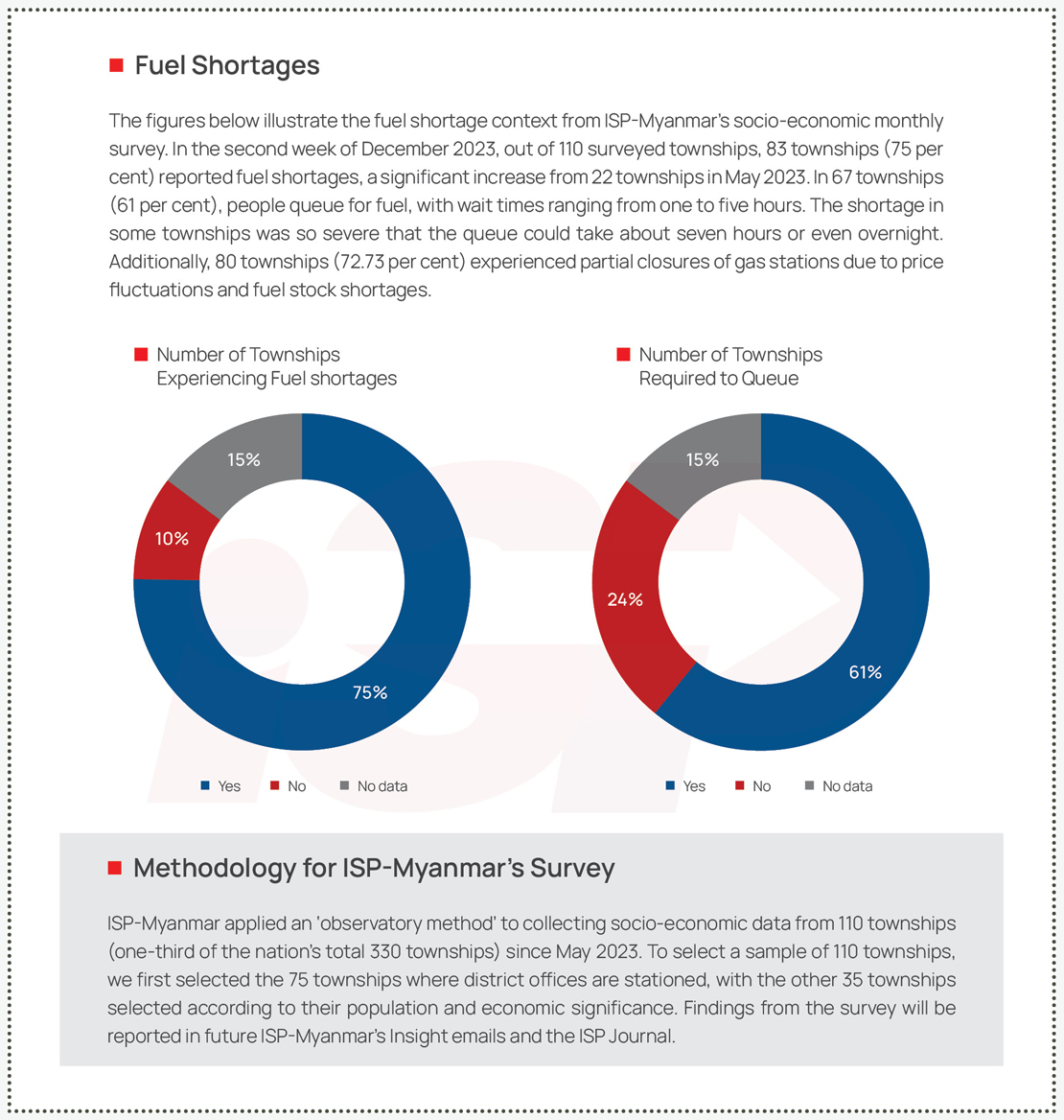

Since the beginning of the operation, almost 91 per cent of China-Myanmar border trade has been clogged, and within more than a month (from October 27 to December 15), Myanmar lost USD 445.5 million worth of trade. Myanmar traders are struggling to export their products to China, directing their export through the Kengtong–Mongla road of Eastern Shan State via the Talone checkpoint; they are encountering higher transaction costs and many of their soft commodities are being damaged. Though the State Administrative Council (SAC) suggested that the traders move their goods through sea routes, this takes time and is not suitable for agricultural products. The expenses incurred for sea-route trading are almost threefold that of border trade.

Regarding the Thai–Myanmar border trade, the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) and People Defense Forces (PDF) have intensified their attacks against SAC forces around Kawkareik Township since November 30, and many trucks with goods are blocked on Asia Highway. Though small vehicles can travel through other roads to avoid the fighting, this allows only for the limited trading of essential commodities. Simultaneously, the Arakan Army (AA) has attempted to gain control of the important border trade routes. When the U.S. and some Western countries imposed economic sanctions against the Myanmar Foreign Trade Bank (MFTB) and Myanma Investment and Commercial Bank (MICB), Bangladesh banks followed the order and suspended banking with their Myanmar counterparts in September. Since then, the border trade with Bangladesh has struggled although the overall impact on border trade was limited. Again, the junta issued an order that exports to Bangladesh must pass through the Sittwe trade point from September 4, 2023 onwards. On the other hand, in the unruly Chin State, Chin resistance forces seized the town of Rihkhawdar in Falam Township, which is a strategic point on the Myanmar–India trade route.

After the military coup in 1988, the former junta was able to bypass international sanctions by expanding and supporting the border trade. However, after the 2021 military coup, international sanctions seem to be more painful for the junta, manifesting with apparent shortages of fuel, essential drugs, and imported foreign goods. The restrictive control of the SAC is driving the crowding out effect on the country’s resources. It is conceivable that with the widespread and intensifying conflict, along with the seizure of strategic border trade routes, Myanmar’s people could be forced to live with prolonged shortages of goods, scarcity, and higher commodity prices.

2.The Chinland Council Conference

The first Chinland Council conference was organized in Victoria Camp of the Chin National Front’s (CNF) headquarters from December 4 to 7, 2023, with participants from the CNF leadership and some former elected Chin representatives. The conference adopted an interim Chinland Constitution. According to the adopted constitution, the delegates of the conference will pursue a Chinland government, a legislative parliament, and a high court within 60 days of its endorsement and these bodies will start to manage the administrative, legislative, and judicial affairs of the Chinland.

After the 2021 military coup, at least 23 resistance forces have newly emerged in Chin State, based on townships as well as tribes. Many towns, including Thantlang, were damaged by fighting, and the junta lost control in many areas of the territories. In recent weeks, Chin resistance forces attacked and occupied at least seven towns of sub-township level, including Rihkawdar, Lalengpi (Lailenpi), and Rezua towns, and military camps at strategic positions in Chin State and along the border with India. Yet liberating the whole Chinland is still far from materializing.

Meanwhile, this Chinland Council conference was organized with the participation of Chin resistance forces after almost three years of the coup. It was attended by CNF leadership, some elected Chin parliament representatives and delegates from fourteen forces. Before this attempt, some Chin leaders strived to organize various ‘Charter Movements’ to unite the residents of Chinland. Some units separated from the emerging Chin forces and founded separate resistance groups because of their ethnic disputes. The CNF formed a Chinland Joint Defense Committee (CJDC) under its leadership on September 30, 2023, with the aim of synchronizing the command-and-control for the military units of at least eighteen different forces. Five other ethnic-based forces also founded a military alliance known as ZZLMS (Zotung, Zophei, Lautu, Mara, Sengthang). Nevertheless, the emerging forces in Chin State after the coup have struggled with disputes about ethnic divisions as well as locality.

The Chin National Council (CDF-Mindat), the Chin National Organization (CNO/CNDF) and the Zomi Federal Union (ZFU/PDF-Zoland) refused to participate in the conference for the reason that this Chinland Council conference was not able to create a unity among Chin groups. These groups also set up their structures of self-administration in their respectively controlled areas.

The conference is also resulting in noises around the Chin polity, as the pact does not represent all parties, so we must be cautious about saying how far the new bodies can be extended and considered representative. On the other hand, there is a body called the Interim Chin National Consultative Council (ICNCC), which is closely affiliated with the National Unity Government (NUG). It is said that the ICNCC is formed according to the Federal Democratic Charter (FDC) and the body is responsible for the Chin State’s legislation, administration, and judiciary powers. It will be interesting to see whether these two councils will be competing or cooperating. The ICNCC nevertheless responded on December 7 with a statement mentioning that they shall not be abolished by any organization, nor shall they transfer their organization to others.

3.The Shift in Fuel Policy and Accountability

Many observers have speculated that the new junta’s policies have been ‘arbitrary’ since its beginning. Many similar situations have been experienced during past juntas. The SAC has known for some time that there will be economic sanctions against it, and since then, it has attempted to control foreign reserves. In addition, the SAC has imposed many restrictive measures on import and export policies.

Since July 2022, the SAC has forcibly converted citizen-owned foreign currencies with the compulsory rate of 1,850 Myanmar Kyat to one US Dollar. Later, the rate changed to 2,100 Kyat for one US Dollar. The whole body of the Myanmar Central Bank came under the control of the junta. The junta imposed a policy in August 2022 by which 65 per cent of exporters’ earnings must be compulsorily converted with the official rate and the traders would be allowed to spend the rest, 35 per cent of their income, at the market rate (the 65:35 policy). The ratio then changed to 50:50, and recently, on December 6, 2023, a more relaxed policy of 35:65 was introduced.

Policy relaxation indicates the last resort when past attempts have failed to work. The new initiative shows that there are shortages of foreign reserves in the hands of SAC. Since December 1, 2023, the SAC’s Committee has reportedly stopped selling US Dollars to importers of fuel, an essential commodity. Previously, the committee oversaw fuel imports, and sold required foreign currencies to the importing companies. Currently, the SAC allows a floating exchange rate (with the market price) on currency exchange; it asks the fuel importers to find the required hard currencies on their own (but the authorities still control the reference prices for fuel).

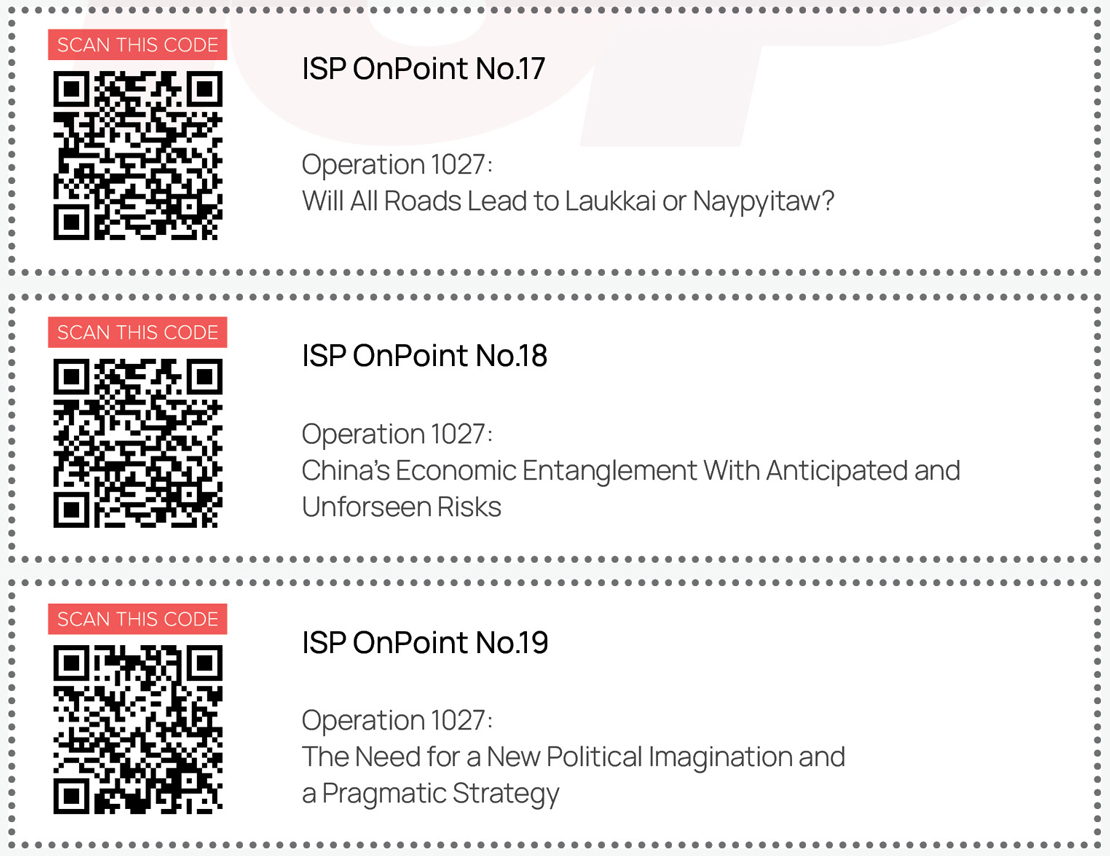

The recent fuel policy change was done without any prior consultation with stakeholders. The SAC thinks the traders and private sector are mere objects, just there to follow its orders. Additionally, official papers have frequently accused the private sector of being greedy individuals. Unlike the Myanmar junta, fuel policy adjustment is usually done with much consideration in other countries, since the changes could lead to significant impacts in the transportation, commercial, logistics, production, and service sectors, as well as higher commodity prices for end-users. The results of the recent fuel policy change are obvious: long lines of individuals, motorcycles, and cars at the pumps. Waiting in long lines devours individuals’ time, and energy and finally leads to panic and makes a black-market inevitable. But the official papers have discounted the event as a temporary problem, a hiccup, or something occurring only in a few scattered places. Nobody takes accountability for this policy.

After a new policy, a market equilibrium between the demand and supply could take time to adjust. There will be ‘losers and winners’, and the losers could be a large population and the negative consequences could be prolonged and extensive. The policy decision could be ‘arbitrary’ but the junta leaders should not forget that it comes with accountability for the consequences.

∎ Trends to be watched

ISP-Myanmar’s OnPoint Analyses on ‘Operation 1027’

Among those developing trends to watch in Myanmar, ‘Operating 1027’ and related events are crucial. The latest development in the fight is that China is mediating ceasefire talks in Kunming, the capital of Yunnan State, between the SAC and delegates of the Three Brotherhood Alliance (3BHA) after 45 days of war. ISP-Myanmar acknowledged that ‘Operation 1027,’ launched by 3BHA and allied forces, has been a significant turning point in the post-coup period. ISP-Myanmar published a series of three OnPoint analyses regarding the operation. In the first analysis, published on November 10, it discussed the ‘signaling effects’ of the operation. The second analysis, published on November 12, discussed the intertwining effects of the war on the economy and China’s response to the war on its border. The last part of the analysis, on December 5, discussed ‘the need for a new political imagination and a pragmatic strategy’. Here is a kind reminder for ISP Gabyin community members not to miss the three-part ISP On Point series.

∎ What ISP is reading?

Han, Enze (2019). Asymmetrical Neighbors: Borderland State Building between China and Southeast Asia. Oxford University Press.

The book is particularly thought-provoking at this moment, even though the book was printed a few years ago. The author is Dr. Enze Han, an associate professor at the Department of Politics and Public Administration at the University of Hong Kong (HKU). [In ISP-Myanmar’s publication, Myanmar Quarterly No. 5, David S. Mathieson provided a review of this book.]

In the opening chapter, the author starts with his trip to Laiza, the Headquarters of the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO). His trip was in around 2013, at the time of Myanmar’s reform under President Thein Sein and before the heavy offensive in that region. Then the author broadened the scope of the ethnic armed forces of Myanmar fighting for higher self-determination, rejecting the control of central power – the Myanmar government. He also discussed the observation of James Scott in The Art of Not Being Governed, about the territories being mountainous, sparsely populated, and ethnically diverse.

Enze Han extended the approach to state building from a new perspective. The notion of state building is the political and historical process of the creation, institutional consolidation, stabilization, and sustainable development of states, from the earliest emergence of statehood up to modern times. In other words, the process involves the spread of state power from the central to the peripheral areas and mostly involves the use of force.

However, this book argues that we should also explain variations in state and nation building across national borders as mutually interactive processes. Thus, the success or failure of one country’s state- and nation-building can depend upon factors beyond its national borders in neighboring states. In the account of the modern history of state and nation-building, China and Thailand have advanced further than that of Myanmar, which creates what the author calls a ‘neighborhood effect’. Because of this effect, Myanmar has yet to reach its control of many of its peripheral areas.

Han emphasizes that in situations where there is a power asymmetry between neighboring states, the effects are further conditioned upon the nature of the relations among these states. For example, suppose the relationship of two states, state A and state B, were asymmetric.If these two states are on adversarial terms with each other while state A is more powerful than state B, this can lead to state A meddling politically or militarily in the affairs of state B, and state B might feel fragmentation of state control on the borderlands.

In contrast, in the situation of an amicable relationship between the two states, state A can still maintain economic domination over state B, and state B could see its economic sovereignty over its borderlands diminish. Being a neighbor to a superpower can create enticements for the people of a less powerful state and act as a ‘centrifugal force’ for many of its residents. This is comparable with the examples of Myanmar’s borderlands.

This book draws the ‘border areas development projects’ of the former Myanmar junta into question, as their efforts may not have been enough to prevent centri-fugal forces from affecting much of Myanmar’s ethnic population. His conclusion on Myanmar is bleak, but it is a book worth reading for many policymakers of Myanmar.

To receive ISP Insight Emails in your inbox, subscribe at this link.