A situation requiring a political-economic perspective

(This article is a translation of the original Burmese language version that ISP-Myanmar posted on its Facebook page on December 31, 2021.)

∎ Preliminary

China’s response to the 2021 military coup seems to have been organized around three factors, in terms of their position on Myanmar. These are: (1) avoiding being labeled as the villain, while also remaining conscious of the political climate, avoiding any situations where western countries might try to reduce the China’s influence on Myanmar and Myanmar’s regional politics (e.g., ASEAN-China relation); (2) slowly establishing itself in the role of powerful decision-maker, without sacrificing their normal strategic security and economic interests, and (3) ensuring a careful handling of certain situations (e.g. COVID), which could negatively impact China due to the unusual social and security issues emerging from Myanmar. There is an increasing need for a political-economic perspective that integrates these three factors to build an understanding China’s economic interests. In the special feature, ISP-Myanmar will present information helpful to establish a clear picture of China’s economic interests in relation to Myanmar from a political-economic perspective.

∎ Summary • Myanmar’s trade with China has decreased in value by over US$ 2.4 billion in the seven months following the coup. China-Myanmar border trade has also dropped to record low in 2021, due to COVID-19 and political instability. Difficulties in the trading sector have also continued as a result of changes in China’s border gate policies, despite the reopening of some border gates. • On top of losing major foreign investments after the coup, China’s monthly rate of investment in Myanmar has also decreased. It now only invests a small amount in existing projects rather than undertaking new projects. Since some Chinese projects have been under attack after the coup, and the anti-regime resistance has become more intense, it will remain difficult to implement new projects requiring large investments, even if the military council’s investment commission is cooperative. • The military council is working to implement China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) projects. However, it is still unable to implement Chinese President Xi Jinping’s core projects. It seems that China is analyzing the unfolding conflict situation, and monitoring the continued rise of anti-China sentiment in the country. Despite this, China did successfully open a new road, connecting it to the Indian Ocean through Myanmar. In addition, 10 months after the coup, China did start to publicly promote the implementation of the CMEC projects. • After the coup, the conflict map between the Tatmadaw and the Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs); between EAOs themselves, and between the Tatmadaw and newly formed local defense forces (PDF/LDF/CDF/KNDF and etc.,) has expanded exponentially. EAOs are also actively trying to secure territorial control and military advantage in the northern Shan State, a crucial path for the new Economic Corridor. These events merit international attention, especially if this is China’s effort to gain geopolitical control of the eastern part of Salween River, or if it is an effort to build its influence more strongly and to guarantee the security of its interests through certain EAOs, which are thought to have a close relationship with China. • China’s response to the 2021 military coup seems to have been organized around three factors, in terms of their position on Myanmar. These are: (1) avoiding being labeled as the villain, while also remaining conscious of the political climate, avoiding any situations where western countries might try to reduce the China’s influence on Myanmar and Myanmar’s regional politics (e.g., ASEAN-China relation); (2) slowly establishing itself in the role of powerful decision-maker, without sacrificing their normal strategic security and economic interests, and (3) ensuring a careful handling of the situation, which will impact China due to the unusual social and security issues emerging from Myanmar (e.g. COVID). Therefore, a political economic perspective which will consider all of the information mentioned above is required to understand China's economic interests. There is an increasing need for a political-economic perspective that integrates these three factors to build an understanding China’s economic interests.

∎ Introduction

After the military coup in Myanmar in 2021, China-Myanmar relations have changed. China has become more careful of openly offering protection to the military dictators, as it did previously during the military rule after the 1988 uprising. However, China continues to protect the military council, which has been facing diplomatic pressure from the United Nations for their claim that the military coup is Myanmar’s internal affair, and therefore not within the UN’s purview.

At the same time, China expressed its hopes for the different factions in Myanmar to resume democratic transition efforts through negotiation, in accordance with the 2008 constitution and other existing laws. Moreover, China also engaged with the Myanmar issue using ASEAN channels, so as not to tarnish its international image. This path was accepted by the United States and other western nations. The military council was not granted the right to represent Myanmar at the United Nations, and the leader of the military council did not get the opportunity to attend China-ASEAN meeting, organized by China.

China does not want to be labeled a villain in the Myanmar affair. It is a complex situation, given that China had a good relationship with the elected government once, but also did not openly oppose the installation of military council. It is not surprising that anti-China sentiment in Myanmar has peaked along with the rise of Myanmar’s Spring Revolution Movement after the coup. Anti-China sentiment is at its highest since the aftermath of the movement promoting the canceling of the Myit Sone Dam project in 2011. During the peaceful anti-coup protests, there were many people who protested in front of the Chinese Embassy daily, asking China not to protect the military council. Even calls for attack to the Chinese projects in Myanmar appeared. However, apart from the event in Hlaing Thar Yar and Shwe Pyi Thar townships in the second week of March 2021, where some Chinese factories were torched, there have been no major attacks on China’s Belt and Road projects, or their petrol and natural gas pipeline projects. Although China’s large projects did not suffer major attacks during the anti-coup movements, China-Myanmar trade has declined to record low since the coup.

The trading sector has not been able to operate normally because of the combination of COVID-19 safety measures and political instability due to the coup. Only a few new investments have been entered, while there has been some further investment in existing projects. It seems that the military council wants to implement the projects under the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor quickly. It is doing everything it can to resume and maintain border trade, and it has also allowed the use of Yuan directly in border trade. Further, the military council issued a statement, requesting the resumption of large projects with China.

In relation to China, which has been the backbone of dictatorships for decades and remains the same today, the bilateral trade and the investment data will reflect China’s political attitude towards Myanmar. Therefore, the state of China-Myanmar trade, investments and Economic Corridor projects will be presented in this special feature published by ISP-Myanmar.

The decline of China-Myanmar trade

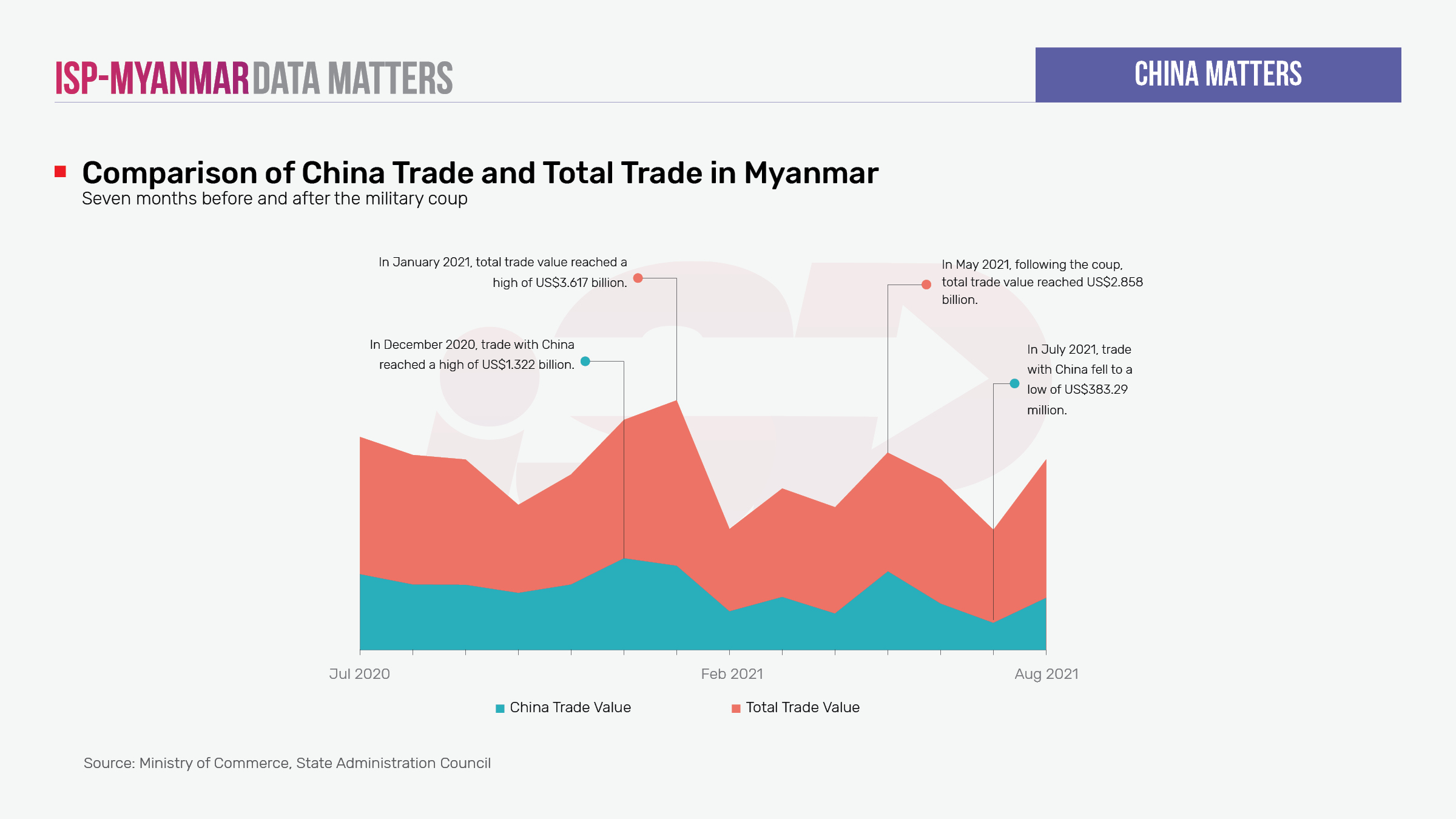

Myanmar’s foreign trade has increased every year since the democratic transition period in 2011. Even during the beginning of COVID-19 (2019-2020 financial year), additional US$ 1.5 billion was traded compared to 2018-2019 financial year. However, Myanmar’s trade sector has declined visibly in 2021. More than US$ 20 billion was traded seven months before the coup (from July 2020 to January 2021). Only US$ 16 billion was traded seven months after the coup (from February to August 2021). Myanmar’s foreign trade has decreased by at least a quarter after the coup.

Myanmar’s major trading partners are China, Thailand, Singapore, Japan and India. Among them, trade with China accounts for one-third of Myanmar’s total trade. Thus, the fluctuating rate of trading with China has a major impact on Myanmar’s foreign trade sector.

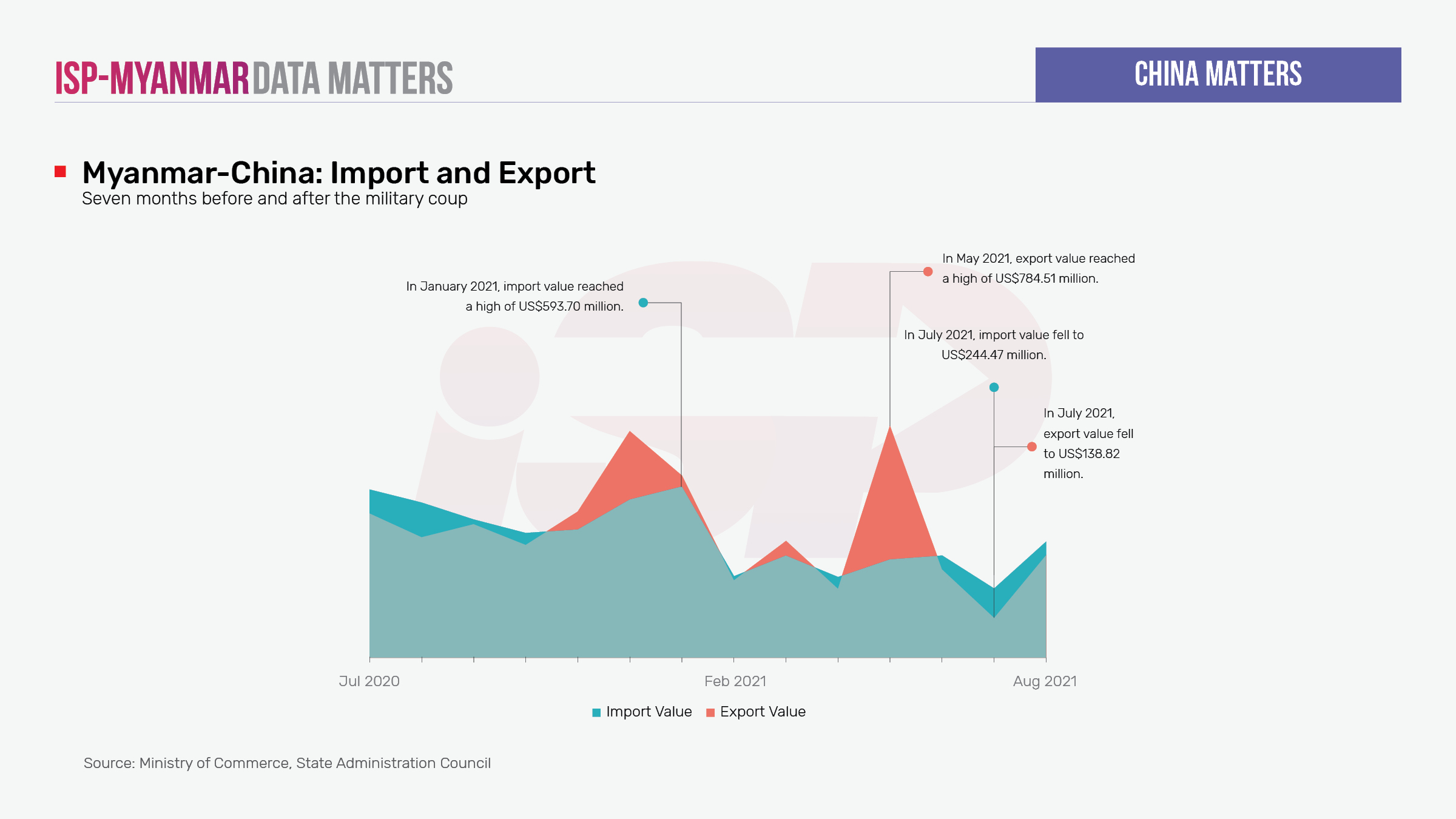

Myanmar’s trade with China has decreased in value by over US$ 2.4 billion in the seven months following the coup. This amounted to more than one-third of China-Myanmar’s total trade. Before the coup, China-Myanmar trade was worth around US$ 800 million a month at least, but it declined to a record low of US$ 380 million in July 2021. This is the steepest decline in China-Myanmar trade since 2019. The main reason for this record low is the decline in border trade.

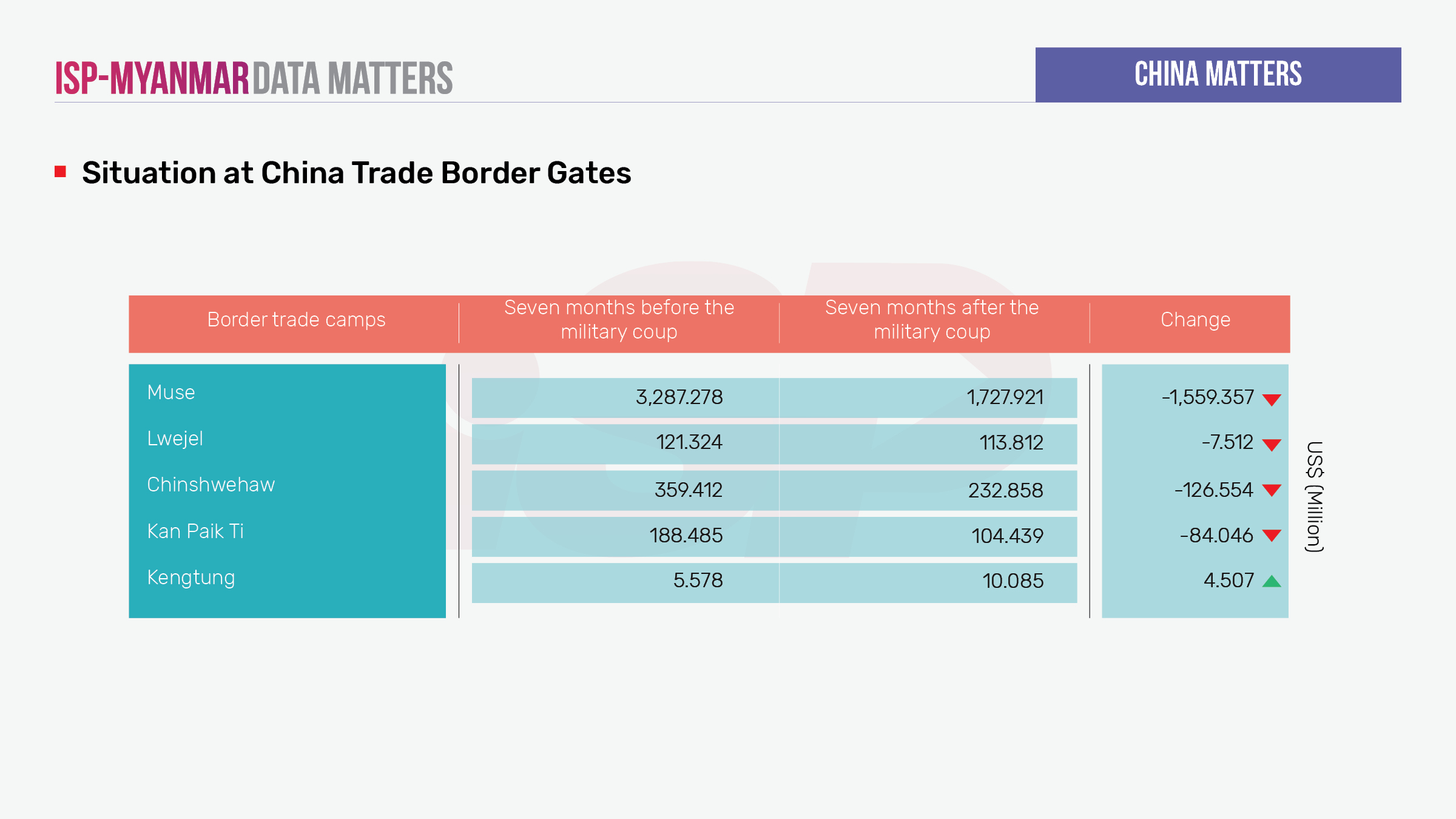

China-Myanmar border trade plays a crucial role in the trading sector of both countries and it accounts for more than half of China-Myanmar’s total trade volume. In July 2021, China-Myanmar border trade almost stopped. There are five trading points officially recognized by Myanmar on the China-Myanmar border. Apart from the Kengtung border trade point, the trade at the other four trading points dramatically declined during the seven months after the coup. The biggest border trading point of Myanmar, the Muse border point saw a loss of US$ 1.6 billion.

The main reason why the border trade has declined is because the Chinese government imposed strict restrictions on border crossings and entries due to COVID-19 cases found in Myanmar, especially in northern Shan State. The border trade came to a standstill when China completely closed most of the border gates in July, due to a third wave of COVID-19 in Myanmar. However, it is important to note that China-Myanmar border trade did not noticeably decline during the first and second wave of COVID-19 (between March 2020 to January 2021) Thus, it is clear that the political instability, caused by the aftermath of the military coup, also had a significant impact on the border trade.

China’s closed border policy was a major blow to the military council. A BBC News report quoted a local merchant from Muse, who said that the Myanmar government earned around US$ 4 million in tax revenue, if approximately US$ 100 million was traded through the border. Compared to seven months before the military coup, China-Myanmar border trade experienced a decline of roughly US$ 1.8 billion, and the military council is thought to have lost over US$ 70 million. The value of exports was, unusually, larger than the imports in in border trade.

The military council has held many meetings in an attempt to reopen the border. Kyin San Kywat gate was opened on a trial basis on November 22, 2021, and Chin Shwe Haw gate was also reopened with restrictions. The amount of logistic expenditure for crossing goods has increased due to the container system and driver-replacement system, restrictions set by Chinese side, and only 20-30 percent of the past trade value was able to operate.

As of now, the percentage of COVID-19 confirmed cases is highest in the northern Shan State, where it shares border with Yunnan Province of China, and there is the added threat of a new COVID variant, Omicron. If the new variant spreads in Myanmar or China, especially in Yunnan Province, it could further impact China-Myanmar border trade. China-Myanmar border trade has declined to record-low in 2021 and it is going to be difficult to return it to normal in a short period.

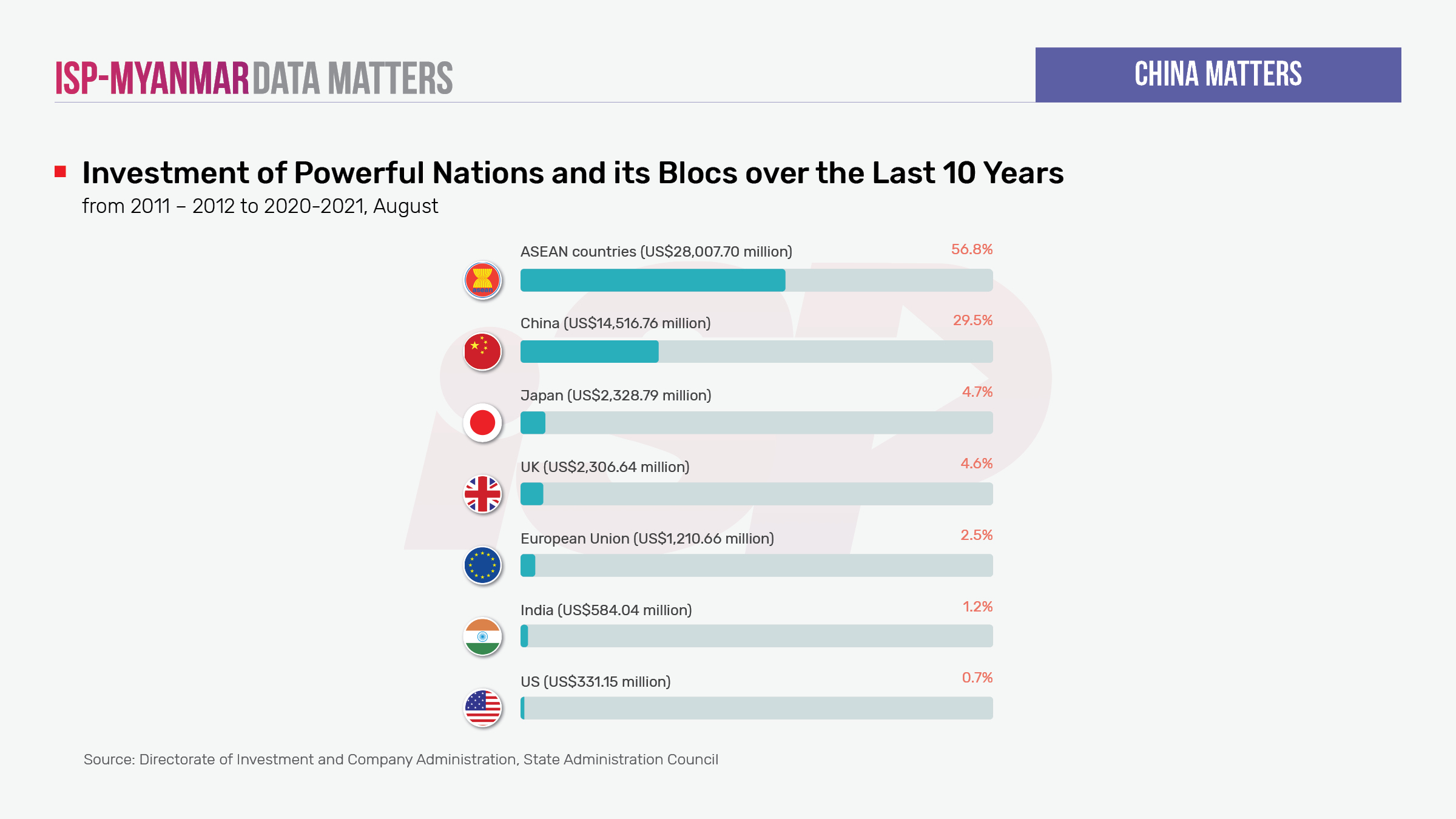

China’s investment

Western countries’ investment was next to nothing after the coup in 1988, and in the years following up to 2010, because of economic sanctions, and the only substantial investments came from China, Singapore and Hong Kong. Then, during a decade of democratic transition, Myanmar was unable to attract many Western investments, with only regional investments performing at all. Having a good working knowledge of how much each country invests in Myanmar’s economy plays an important role in understanding the major countries’ influence in Myanmar’s affairs.

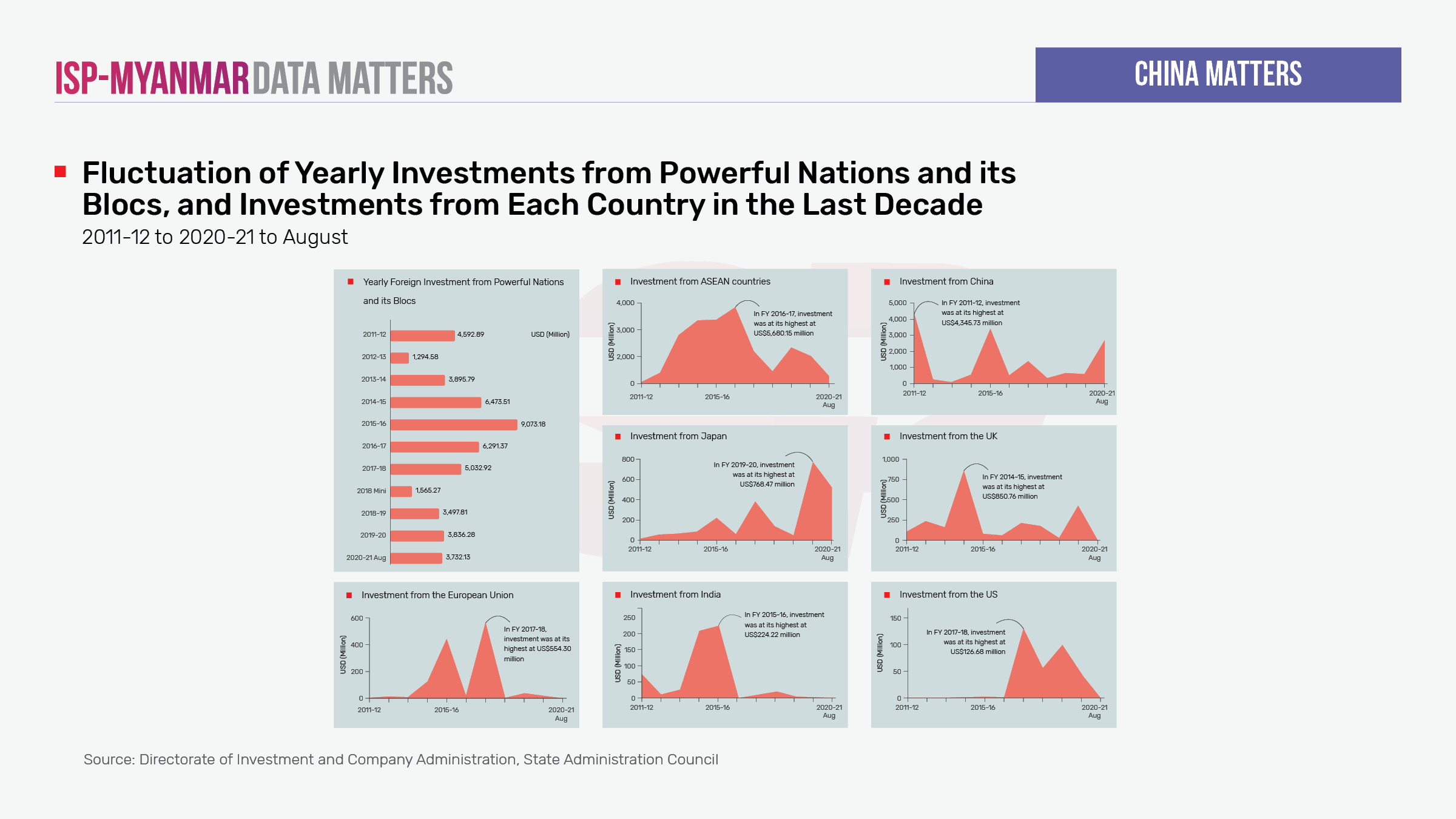

In the last decade, ASEAN countries invested over US$ 28 billion in total and China invested over US$ 14.5 billion. The United States invested over US$ 300 million, the European Union invested over US$ 1.2 billion and the United Kingdom invested over US$ 2.3 billion. It is clear that these investments were small when compared to regional countries.

There were also many dramatic rises and falls in investments based on the political events in Myanmar. For example, Chinese investment has dropped successively 18 times after the Myitsone Dam project was suspended in 2011. The 2017 Rohingya issue also has a major impact on the investment sector. The 2021 military coup caused a major decline in foreign investments.

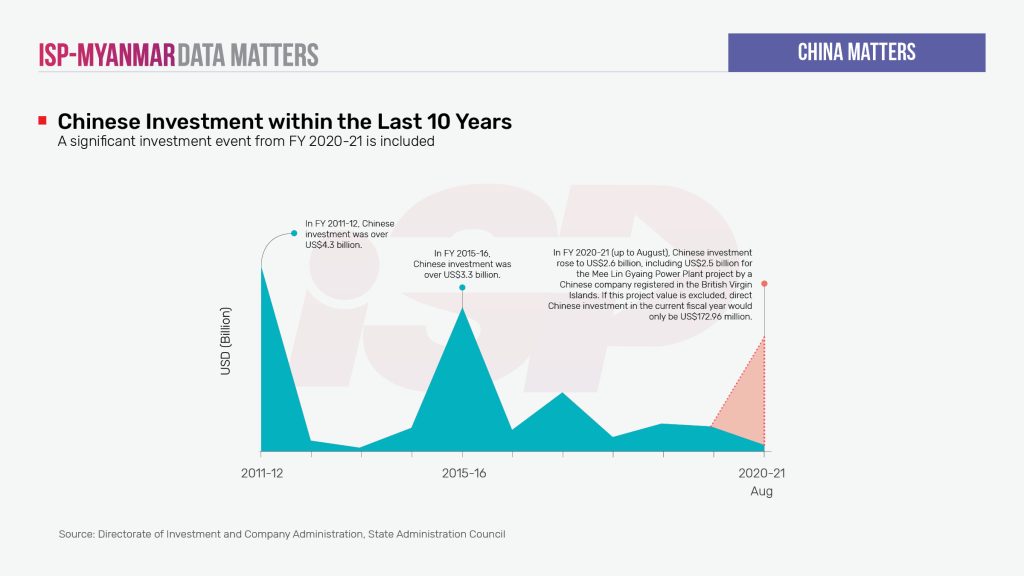

It is clear that the investments from the ASEAN regional countries have drastically declined during the 2018-2019 financial year and the 2019-2020 financial year (during the COVID-19 pandemic). The military coup also caused another blow to an already declining rate of trade. Although Chinese investment in the 2020-2021 financial year has increased, it was not direct investment; investments are made indirectly through the British Virgin Islands.

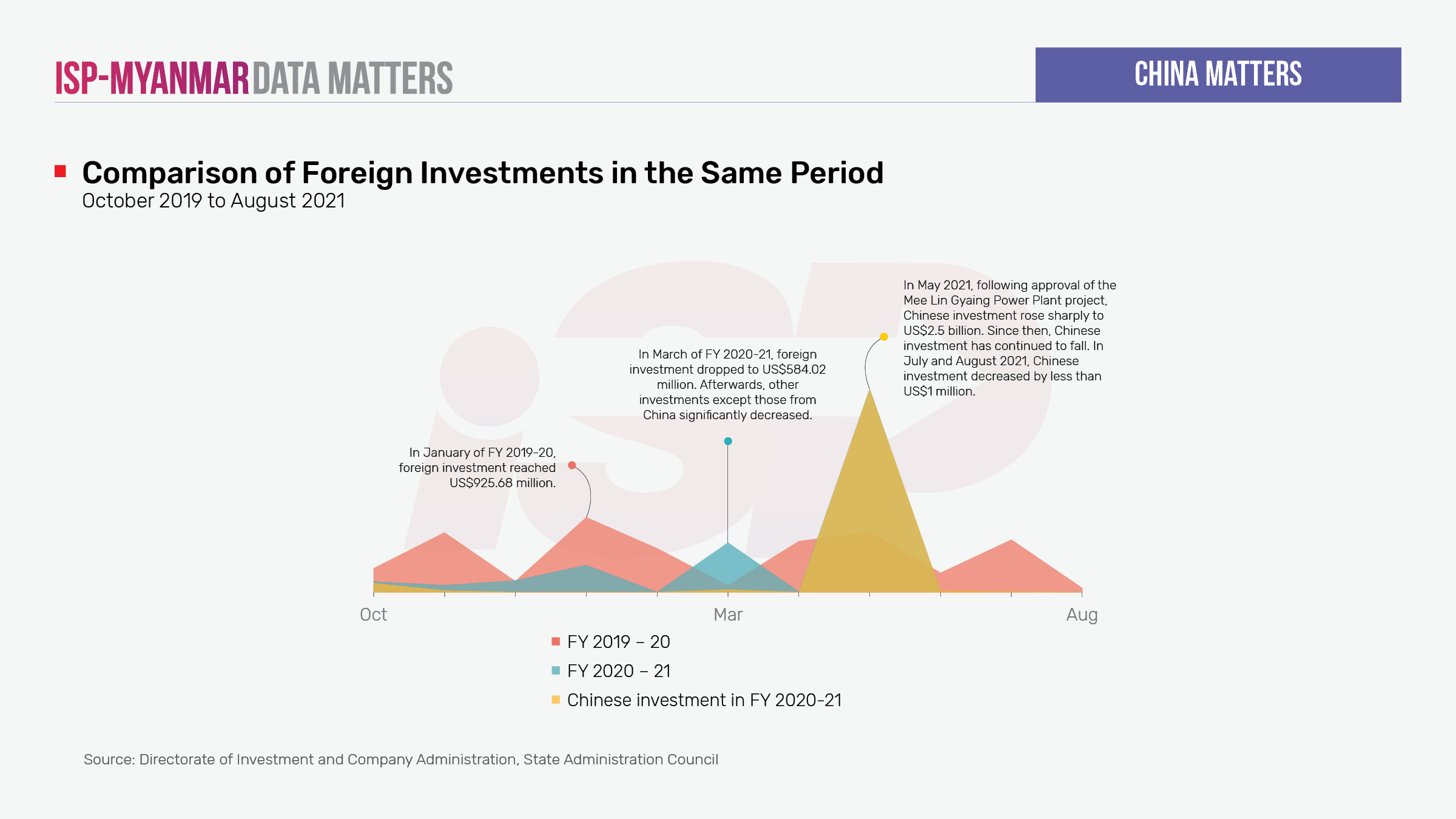

In the aftermath of the military coup, more than twenty international investments were suspended and pulled out of Myanmar altogether, but Chinese businesses and projects remain. However, Chinese investment did decline drastically in the seven months after the military coup.

Between July and August 2021, less than US$ 1 million was invested. Such investments are not in new projects, but additional investment into the existing ones. Apart from the Chinese investments in June, July and August of 2021, there was no other foreign investment at all. Moreover, one of Hong Kong’s major businesses, V Power, also suspended its project without extending the contract for Myingyan energy project No.1 and Kyauk Phyu energy project No. 2.

The investment in the energy sector was the highest in comparison to investments in different sectors for the 2019-2020 and 2020-2021 financial years. Since the military council has allowed more than US$ 2.5 billion worth of Chinese investment projects, such as the Mee Lin Gyaing energy project, the investment in the energy sector has now increased to almost twice that of the 2019-2020 financial year. Chinese State-Owned Enterprises (SOE) also participated in the tender process of solar energy projects.

In the manufacturing sector, total investment has dropped from over US$915 million (Oct 2019 to August 2021) to 262 million (Oct 2020 to August 2021). Moreover, investments in agriculture, livestock and fisheries, transportation, real estate and other sectors have also significantly decreased.

It seems that the military is trying to revive the situation after the coup by facilitating major projects which are important priorities for China. In May 2021, the military council’s DICA approved the proposal for the Mee Lin Gyaing project, which is a part of China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC). The investment for this project came through a company registered in the British Virgin Islands. China’s investment in Myanmar reached about US$ 2.5 billion in the seven months after the military coup, if this project is included. If this project were not included, China’s investment would be a little over US$ 33 million in the period after the coup until August 2021.

China has been handling the ongoing situation delicately, due to political instability and the rise of anti-China movements. Both sides seem to be aware of the possible repercussions of the March 2021 arson attacks on the Chinese factories: the military council declared martial law in some of the areas where the attacks took place, and heightened security for China’s major projects. Moreover, the Chinese government’s media mouthpiece, the Global Times newspaper, reported that since the announcement of a nationwide defensive war by the National Unity Government on September 7, 2021, Chinese projects in Myanmar were suffering many obstacles. This shows that China is concerned about the safety of its interests in Myanmar. Even if the military council allows the Chinese investment officially, the implementation of the projects will still be difficult to realize.

The Belt and Road initiative projects

The China-Myanmar Economic Corridor, which is a part of the Belt and Road Initiative was first introduced under the NLD government. The Economic Corridor, shaped like the letter “Y”, will be over 1,000 miles (over 1,600 km), connecting Shan State, Mandalay Region, Kachin State, Nay Pyi Taw, Yangon Region and Rakhine State with border economic zones, highways, a high-speed electric railway, new industrial townships, inland ports, a deep sea port, special economic zones and warehouses.

China officially proposed at least 33 Belt and Road Initiative projects during the NLD government’s tenure. In fact, China has been trying to implement large strategic projects since the former military government, and the U Thein Sein government – even before the Economic Corridor plan was officially announced.

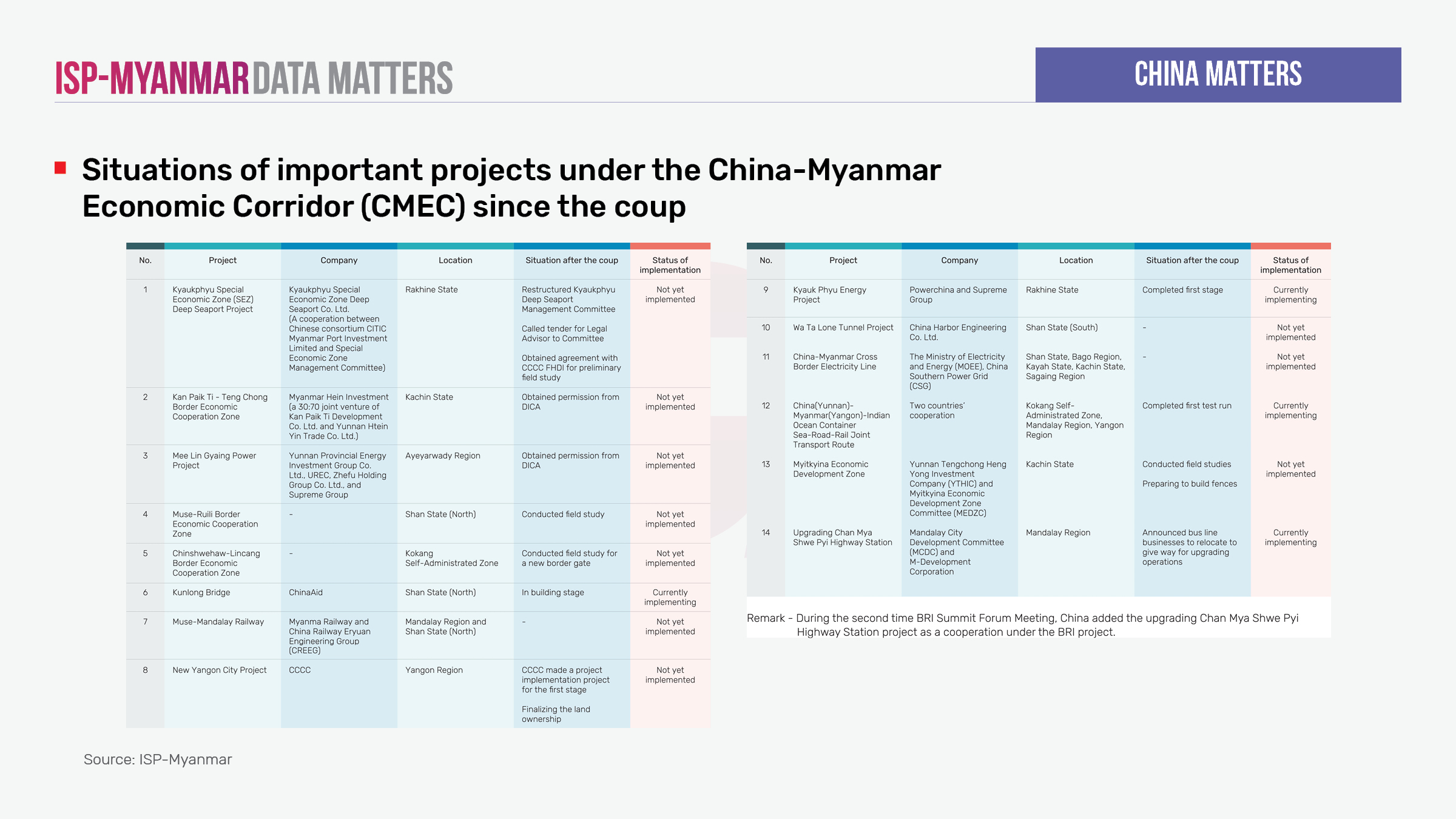

China frequently tried to put pressure on the NLD government to implement the Economic Corridor projects. For example, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Myanmar in 2020 was aimed at expediting the “Kyauk Phyu deep sea port and special economic zone project, the New Yangon City project and various border economic cooperation zone projects”, which are regarded as the core projects for the CMEC. However, these projects could not be implemented under the NLD government due to the rechecking of project proposals, reduction in investment, the renegotiation of share divisions and the invitation of investors from other countries.

After the coup, the military council tried to implement the core projects of the Economic Corridor as well. A month after the coup, it re-established committees to handle the policy, management and implementation to resume Belt and Road Initiative projects.

Moreover, the military council’s investment commission approved the proposal of the Mee Lin Gyaing project, worth US$ 2.5 billion, and the Kanpaikti project, worth US$ 22.4 million, which were under review during the NLD government. However, these two projects still cannot be implemented due to political difficulties and COVID-19 restrictions.

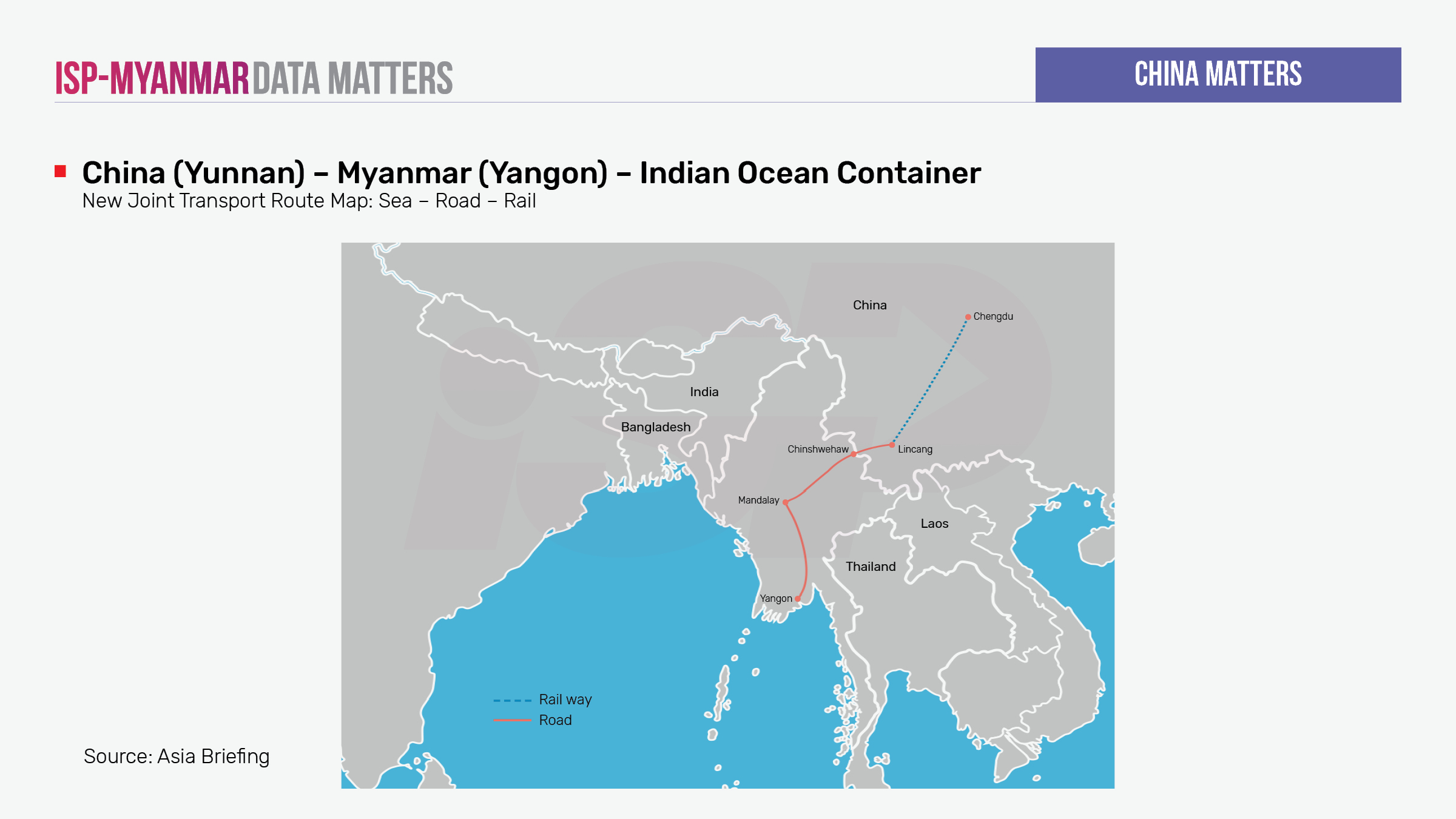

The most important project in the China-Myanmar Belt and Road Initiative project 2021 is the opening of China(Yunnan)-Myanmar(Yangon)-Indian Ocean container sea-road-rail joint transport route. Thus, the military council announced that it aims to finish building a new Kunlong bridge in northern Shan State by 2023—crucial for connecting the Chin Shwe Haw border economic cooperation zone project that is vital for the joint transport route mentioned above and China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Although there were field studies of both countries and minister-level discussions to open a new border gate of Chin Shwe Haw-Mengding, which will serve as a main route for China-Myanmar border economic cooperation zone, no progress has been made due to COVID-19, political tension and inequality in border trade.

However, the Chinese Embassy in Myanmar’s Facebook page has now posted about implementation of the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor for the first time after the military coup at the end of 2021. It is important to keep in mind that China tends to publish its perspective when it changes its policy. Although it is possible that there will be efforts to get approval for the projects, which are under discussion, at a faster pace, the challenges to implement such projects on the ground are going to persist due to political instability and COVID-19 restrictions. Specifically, China’s strict policy in controlling borders by closing the trade gates and building fences completely contradicts its Economic Corridor plans, which focus on cross-border relations between two countries. Moreover, the hostile attitude of Myanmar’s citizenry towards China and its projects is going to remain a big challenge, given their memories of the Myitsone Dam project.

China’s investment projects and possible conflicts

Most of the strategic projects within the Economic Corridor in Myanmar are in ethnic areas where the majority of armed conflicts are occurring. In the northern Shan State, where at least seven EAOs are actively operating, there are major border economic cooperation projects, and the Muse-Mandalay railway-road is also going to be built across many townships where armed conflicts continue to break out.

The conflict map changed markedly after the coup, due to the conflicts that broke out between the Tatmadaw and EAOs, between EAOs themselves and newly emerged local defense forces (PDF/LDF/CDF/KNDF etc.,).

Moreover, a territorial war between the Restoration Council of Shan State (RCSS/SSA) and the Shan State Political Party (SSPP/SSA) in northern Shan State, where crucial parts of the Economic Corridor projects exist, is also shaping the conflict.

SSPP cooperated with the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) and the United Wa State Army (UWSA) (groups that are thought to have close ties with China) launched an offensive war against RCSS, which led RCSS to lose many areas that it had previously controlled in Shan State. Among such areas, Man Hio town (surrendered by RCSS) was where China was preparing to build a border economic zone. Furthermore, RCSS has lost areas within the Kyaukme Township, which Muse-Mandalay railway road will cross, and also has had to give up Loi Lin town in Southern Shan State.

Significantly, a new China(Yunnan)-Myanmar(Yangon)-India Ocean container sea-road-railway joint transportation route was launched at the end of August 2021 amid heavy fighting in northern Shan State, where the EAOs, which have close ties with China, are gaining ground against the RCSS.

Before it started running, Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) and Kachin Independence Army (KIA) engaged in intense battles with the Tatmadaw troops almost every day in Monekoe, Muse Township in July 2021. The clashes with MNDAA continue to this day.

MNDAA expanded its activities in Monekoe, Phaung Sai and Hsenwi (Theinni) regions, although it was initially only active in the Kokang region. It is important to note that the Hsenwi route will become a part of the sea-road-railway joint transport route from Chin Shwe Haw. The Tatmadaw troops have clashed intensely with MNDAA in the Muse Township, as well as Monekoe and Kyu Koke-Pang Hseng towns. It is obvious that MNDAA wants to expand its territory along the China-Myanmar border. It also clashed with the military troops in Kyu Koke-Pang Hseng region where China is hoping to build a border economic cooperation zone. There were some skirmishes where artillery shells landed in China, due to the clashes between MNDAA and the Tatmadaw, and China immediately summoned Myanmar’s Ambassador and issued warnings.

While the number of clashes and shootouts across the country is increasing, it is important to wait and see if the military activities of EAOs, which are often thought to have close ties with China in Shan State—especially with regard to activities near Economic Corridor, are efforts to gain more territorial control and military advantage. China is may be preparing to gain control of the eastern part of Salween River, or these efforts might be to build stronger influence through allied EAOs, and to guarantee security for Chinese interests.

∎ Conclusion

When analyzing trades and investment data, there are three fundamental facts which have shaped China’s policy when it comes to Myanmar affairs. Firstly, it is clear that China is keen to avoid the socio-economic issues arising from COVID-19, as well as political instability, by closing down border trade to contain COVID-19 and building more border fences. Although there have been attempts to completely reopen border trade, the chances of this happening soon are low, due to the dual impact of the pandemic and the political situation. Secondly, the territorial control operations of the EAOs that have close relations with China in the areas where major Chinese projects are located cannot be dismissed – especially in the context of China’s geopolitical influence on Myanmar affairs. Lastly, despite the military council’s attempts to revive the Economic Corridor projects and draw in more investments, the lack of significant Chinese investment shows that China is waiting to implement the projects due to political sensitivities (to avoid being labeled as the villain internationally and domestically).

Despite the military council’s efforts to begin work on the Kyauk Phyu deep sea port and economic zone project, the Muse-Ruili border economic cooperation zone, the New Yangon City Development project and the Chin Shwe Haw-Lin Cang border economic cooperation zone projects, there has been no major progress made in any of these areas. There have been discussions about the implementation of other major Chinese projects, but again, nothing has actually happened yet.

The old-fashioned view – that “every government that comes to power in Myanmar will be protected by China” – is no longer sufficient, especially considering China’s current level of economic interest. China’s response to the 2021 military coup seems to have been organized around three factors, in terms of their position on Myanmar. These are: (1) avoiding being labeled as the villain, while also remaining conscious of the political climate, avoiding any situations where western countries might try to reduce the China’s influence on Myanmar and Myanmar’s regional politics (e.g. ASEAN-China relation); (2) slowly establishing itself in the role of powerful decision-maker, without sacrificing their normal strategic security and economic interests, and (3) ensuring a careful handling of the situation, which will impact China due to the unusual social and security issues emerging from Myanmar (e.g. COVID). Therefore, there is an increasing need for a political-economic perspective that integrates these three factors to build an understanding China’s economic interests.