This article assesses media freedom under the NLD Government by analyzing the situation of legal reform towards existing laws, which are frequently used to persecute journalists; the number of journalists being prosecuted; and the progress towards achieving right to information.

Reform of existing laws frequently used to prosecute journalists

The following laws which include – News Media Law, Unlawful Associations Act, Burma Official Secrets Act, Section 500 and 505(b) of the Penal Code, Telecommunications Law, Law Protecting the Privacy and Security of the Citizens, and Counter Terrorism Law are frequently used to bring criminal charges against journalists.

Among these laws, the Telecommunications Law and Law Protecting the Privacy and Security of the Citizens were revised only superficially while it is still a long way to be able to amend other laws meaningfully. Civil society organizations, media organizations, and even the Myanmar Press Council have struggled together to amend the News Media Law but were neglected by the NLD Government and the Parliament.

In article 21 of the current version of the News Media Law, it is mentioned that if any media personnel are assumed breaching the responsibilities or code of conduct specified in article 9, the aggrieved party shall have the right to complain to the Council first. However, at the same time, the phrase “shall have the right to complain” can also be interpreted as that same party can immediately file a case with the police as well as take the matter to court without going first to the Council. Due to this particular shortcoming, role and authority of the Press Council whose mandate is to protect media freedom by acting as an effective mediator for media disputes has gradually declined, that further leads to low level of trust towards the Council by journalists.

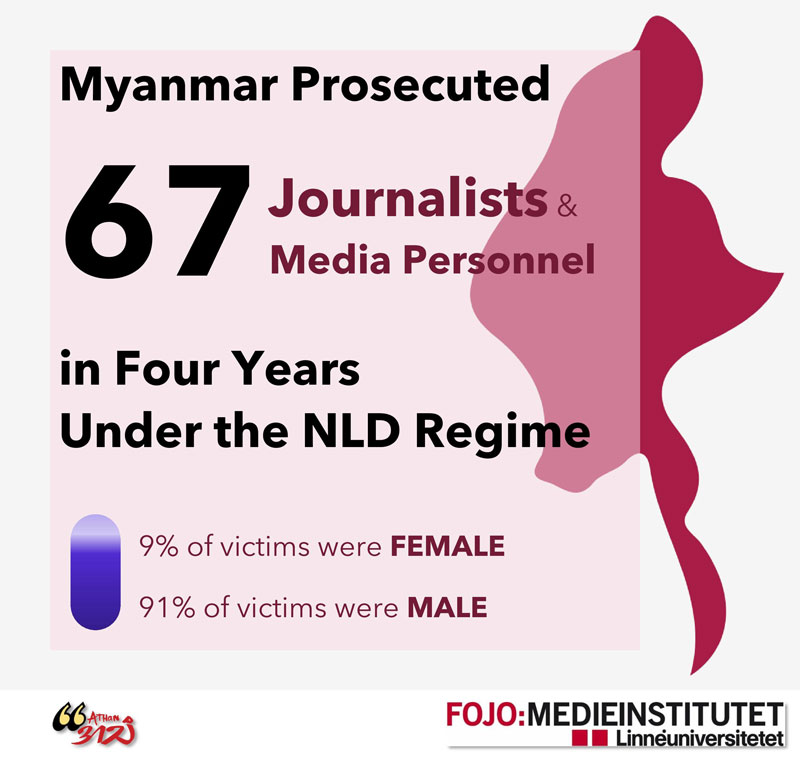

Number of prosecuted journalists

Under the administration of NLD Government, number of journalists being prosecuted reached up to 67, which is twice the number from the USDP Government period. Telecommunications Law was most frequently used, followed by the Counter Terrorism Law.

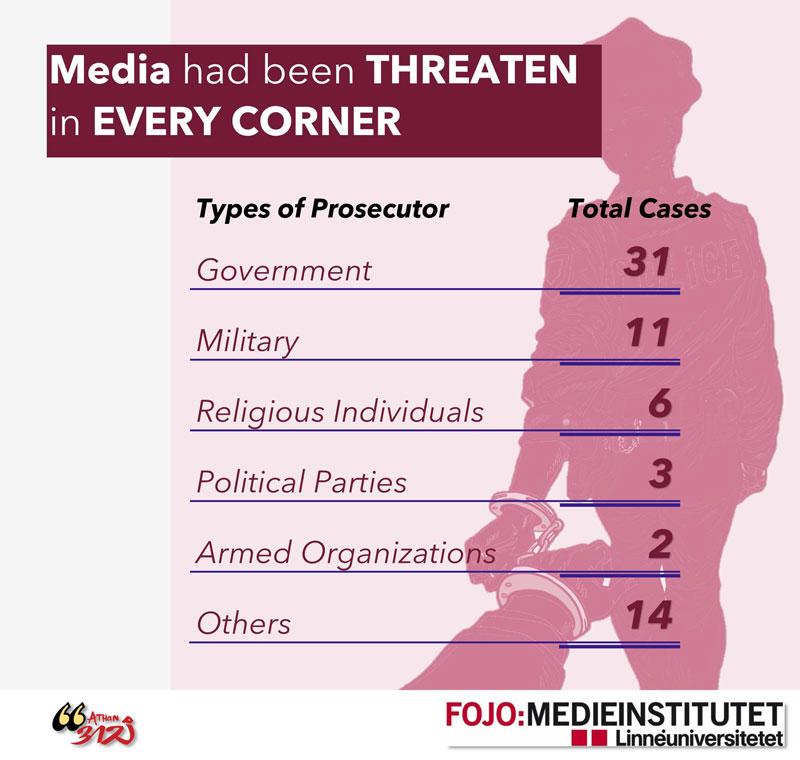

Majority of prosecuting parties came from the Government side, leading the trend with 31 cases filed, while the military followed suit with 11 cases. The military has since withdrawn seven cases while the Government did the same for only one case which was charged against the Eleven Media Group for reporting on financial mismanagement issue of Yangon Bus Service (YBS).

Situation on Right to Information

Right to information is crucial for every citizen, especially for media and journalists, in order to have access to Government archives, official administrative records or private business dealings.

Collected effort put together by civil society organizations to pass the Right to Information (RTI) Law has reached an impasse at the hand of Ministry of Information, since the recommended draft has been submitted in early 2018. At the end of 2017, the draft was developed with the contributions from both civil society organizations and the Ministry of Information, the latter has consistently failed to submit to the parliament for further due process.

Instead, National Record and Archive Law was passed without any consultation with civil society organizations, and stakeholders from the media sector. The new National Record and Archive Law enacted in December 2019 replaced the previous National Record and Archive Law passed by the State Law and Order Restoration Council in 1990. According to the law, the public has a right to view and use the government records and archives only when the duration imposed by the respective security level has expired.

In terms of the security level and duration, article (12) of the law categorized different status as followed –

a) if classified as ‘top secret’, the duration required is 30 years,

b) if classified as ‘secret’, 25 years,

c) if ‘confidential’, 20 years, and

d) if ‘restricted’, the duration is 5 years.

Moreover, in the article 13(a), it is mentioned that the National Archives of Myanmar can continue to limit public access and use, even after the security requirement of the archives has expired. Hence, the law in a way provides full authority to the Government to deny and block the public’s right to access information arbitrarily.

Based on the existing law, the Government can determine any type of information to be ‘top secret’ which legally allows them to restrict information from the public for 30 years or more. There is also no provision in the law to appeal the Government’s decision. By exploiting the ‘top secret’ security level categorization, the Government can cover up corruption, mismanagement and human rights violations committed at ease. Hence, it becomes extremely important to cancel the National Record and Archive Law which restricts public’s right to information and instead, previous efforts to develop Right to Information Law (RTI Law) should press on.

Right to Information being Disconnected

The two most outstanding cases regarding violations of right to information include cutting off the internet in eight townships of Rakhine State, and Paletwa township of Chin state in June 2019, and shutting down over 200 websites including some media outlets by the telecommunications operators due to the Government directive in March 2020. Among the websites include a legally registered Rakhine-based Narinjara news media, Development Media Group (DMG), Mandalay-based Mandalay In-Depth News, Voice of Myanmar (VOM), and Tarchileik-based Mekong News.

In light of all these changing contexts, we can assume that media freedom has not progressed but has regressed under the NLD government administration. With the 2020 elections taking place this week on 8th November, soon a new parliament will be formed. In the new parliamentary context, it is crucial to amend and abolish the laws which have been choking media freedom for a long time. For democracy to thrive within the country, media freedom is like a lifeline. So, in essence, trying to achieve this goal without guaranteeing media freedom is similar to forcing to row a boat forward which is anchored to the shoreline.

— END —

Also can read this article in Burmese

*Maung Saungkha is an executive director and one of the founders of Athan, Freedom of Expression Activist Organization, which is taking a leading role of promoting freedom of expression, as well as legal reform in Myanmar.

*This article is originally published for Fojo Media Institute ( https://fojo.se/en/myanmar-legal-reform-is-a-must-for-genuine-media-freedom/ ) on 2nd November 2020.