This event was held on May 11, 2024, exclusively for ISP Gabyin Community members. This English translation of the event’s recap memo was published on June 5, 2024. DVB broadcasts the recorded video with English subtitle of the live event on its channel regularly on Mondays and Wednesdays.

Greetings to all Gabyin members who have come to attend today’s program, 30 Minutes with the ISP. I am Cho Zin, your MC for today’s program. As ISP-Myanmar’s new conception, we’ll soon begin “30 Minutes with the ISP” the second episode of the talk show. The first episode took place on April 6, 2024, discussing “Introduction to Sino-Myanmar Relations Survey 2023, Perceptions of Myanmar’s Key Stakeholders”. Today’s discussion topic is “Naypyitawlogy – Three Words Characterizing Naypyitaw.” As the event title suggests, we’ll adhere to the 30-minute time limit and try to wrap up the program in time. We endeavor to share some food for thought within this time limit.

Panelists for today are Mr. Kyaw Htet, the Program Head of Conflict, Peace, and Security Program (CPSP), and Miss Saung Yanant who is a CPSP Program Associate. Without further ado, let’s begin the discussion. I will give the floor to the panelists, Mr. Kyaw Htet and Miss Saung Yanant.

Naypyitawlogy

Three Words Characterizing Naypyitaw

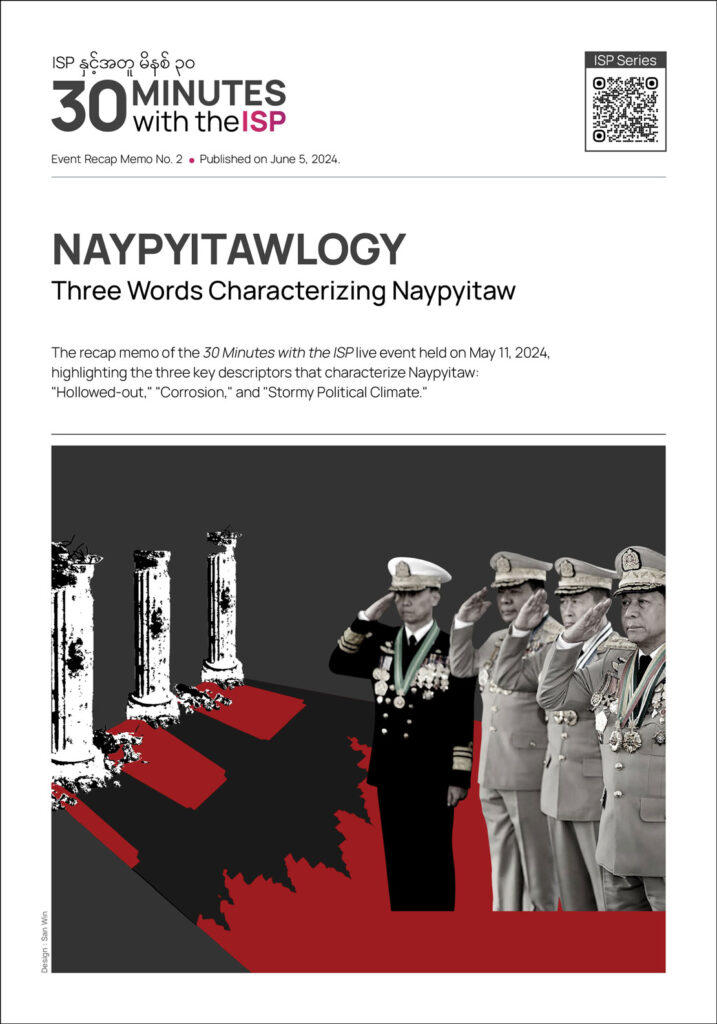

First and foremost, I’d like to say Mingalarbar. I’d like to welcome and express my gratitude to everyone who came to today’s ISP event. The discussion will be on one of ISP-Myanmar’s key research topics, which is “Naypyitawlogy.” Firstly, what is Naypyitawlogy? And why is it worth studying? As described in our concept note, in studying authoritarian regimes worldwide, there are studies such as Kremlinology, Pyongyangology, and Pekingology. Similarly, ISP-Myanmar is studying the shifts and changes in the State Administration Council (SAC) under the Naypyitawlogy topic. When examining the Myanmar Armed Forces (MAF) and political strategies of the generals in Naypyitaw and the shifting internal dynamics, many discussions on the events in Naypyitaw often resemble jumping to conclusions with a desired outcome rather than conducting a systematic analysis of the SAC. Fact-based discussions about possible outcomes and scenarios are rare. From a research standpoint, to comprehend or interpret the changes and events in Naypyitaw the lack of data-backed discussion stems from the absence of a relevant epistemological framework Without a proper framework, it might result in being overwhelmed by events limiting our understanding of events happening repeatedly in patterns and anticipating potential scenarios. To stay ahead of the curve, we, ISP-Myanmar, will be exploring the intricacies of “Naypyitawlogy.”

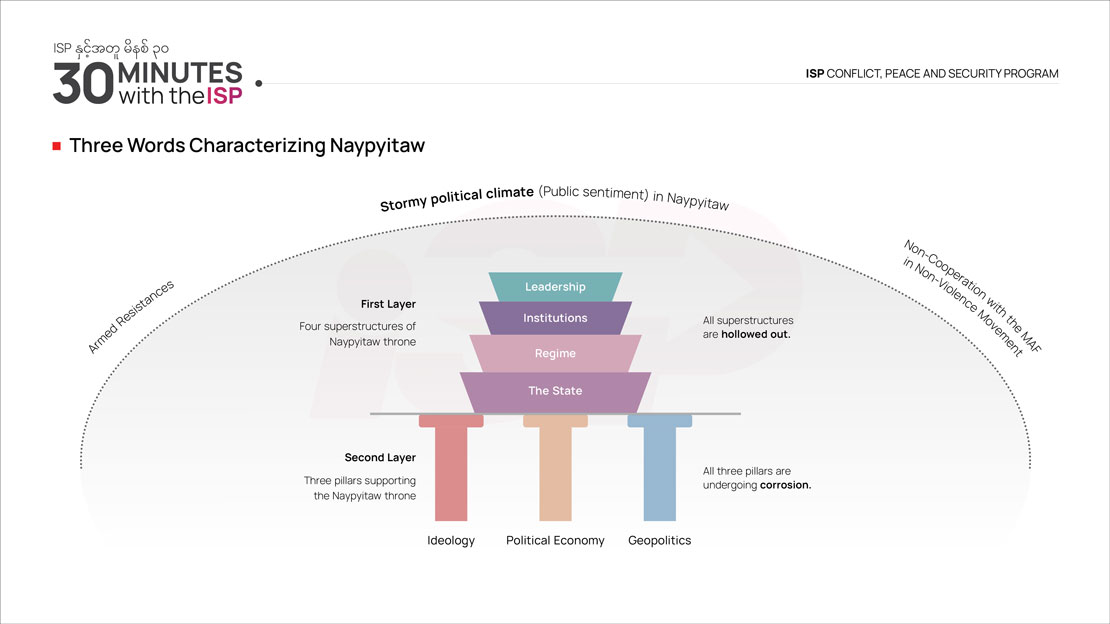

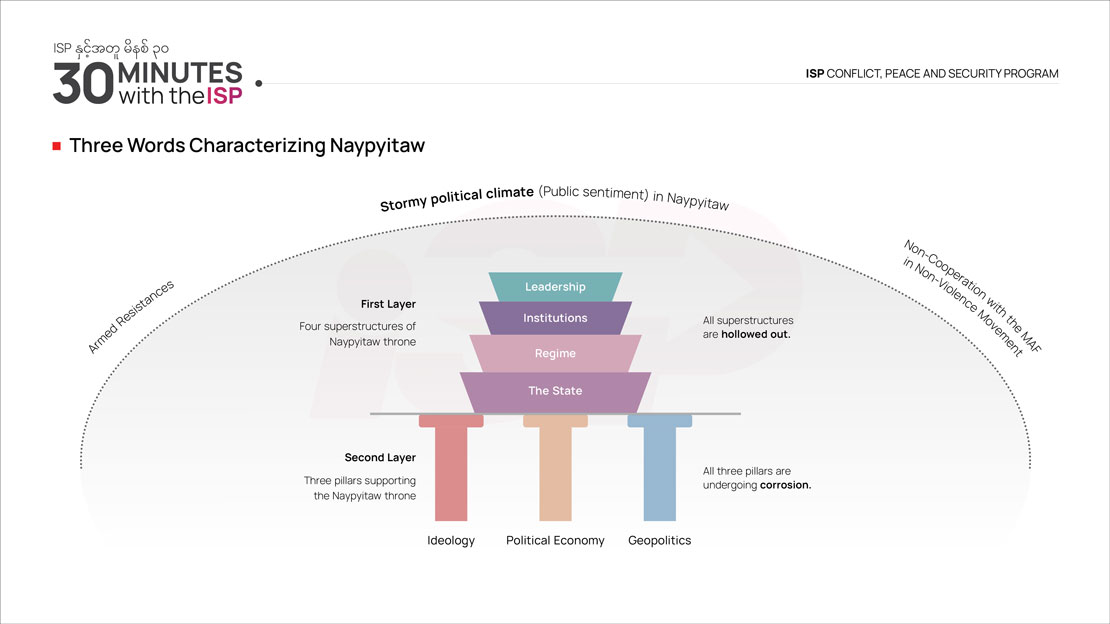

Our discussions will unfold in three parts as we can see it on the screen. Firstly, we’ll explore the nature of Naypyitaw throne’s superstructures – here are what we call the “hollowed-out factors”. Next, we’ll examine the pillars that have historically upheld the junta’s authority. We see the corrosion of these pillars now and we’ll touch on this. Last but not least, we’ll analyze the current political climate surrounding these situations. The things embroiled in the political climate, in the encompassing atmosphere, is also important.

Firstly, when examining the factors influencing the center of power, we can identify four fundamental superstructures. The first pertains to “the state” and its ability and effectiveness in controlling its bureaucratic apparatuses. Secondly, we consider the regime and how it sets up the rules of the game to bolster its authority and drive policies. Particularly, we mean to study if the regime can still address the political problem within the constitutional framework, to what extent to seek political solutions in the conflict and to what extent the situation is deteriorating. The third aspect revolves around the functionality of the power-supporting institution that props up the regime. It is also important to note how this institution views the regime. The last aspect is the regime’s individual leadership. How does the cabinet operate under one’s leadership? Is one solely dictating the decisions for all affairs? And is this approach effective? These four points I just mentioned summarize the hollowed-out superstructures in Naypyitaw’s throne. Only if we understand these factors, we’ll be able to see what is happening in Naypyitaw and what the figures in Naypyitaw are thinking.

And, there are no check and balance mechanisms among these four factors, the state, the regime, the power-supporting institution which props up or rides the regime, and the individual leadership. Instead, they are conflating as one that collaborates to oppress the people. Moreover, instead of distributing power among the executive, judiciary, and legislature, all the power institutions are monopolized by the Myanmar Armed Forces (MAF). In other words, the 2008 Constitution establishes a regime that grants the MAF veto power. In this regime, the MAF, which is basically a part of the state apparatus, has taken control of the state and is now using it as a tool of oppression. At the same time, the dictator who leads this state apparatus exercises discretionary power. So, this discussion will center on leadership and how the leadership problem leads to other hollowing-out problems within the system.

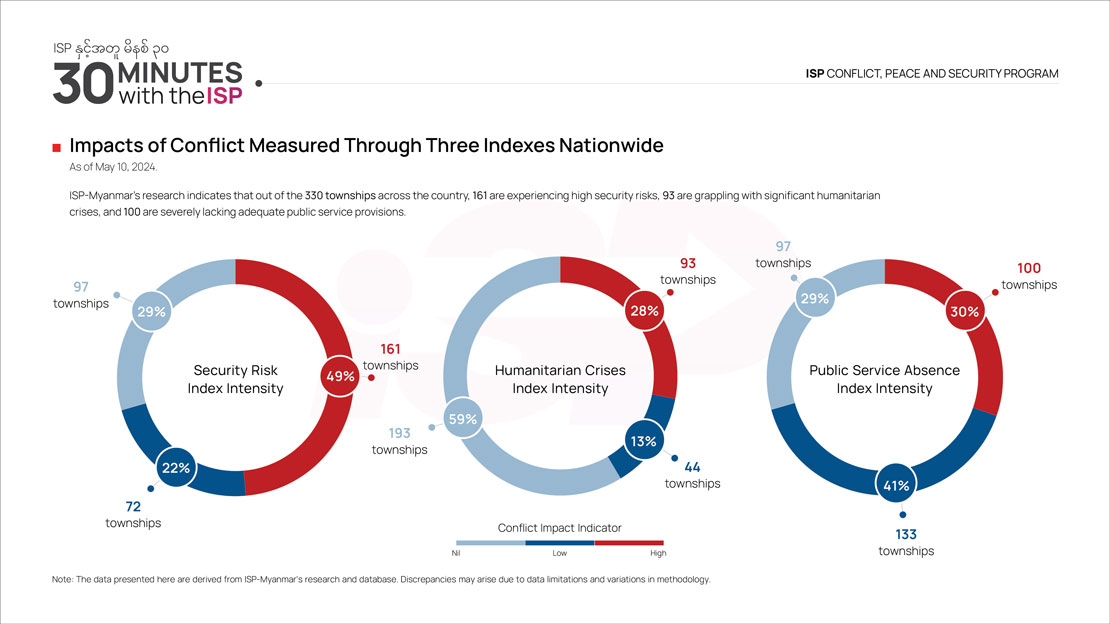

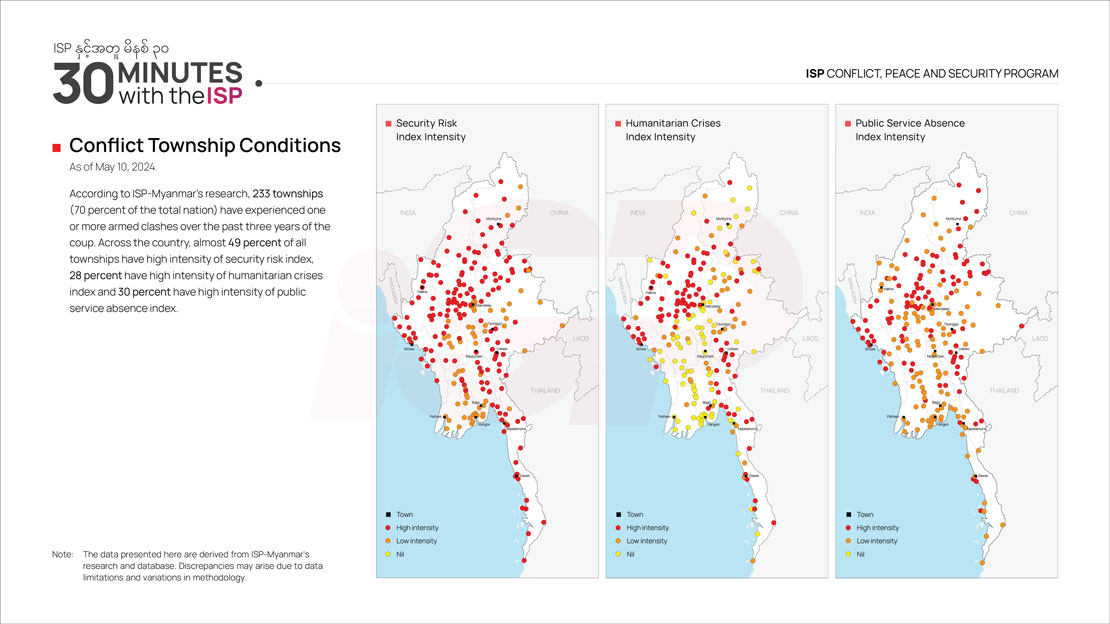

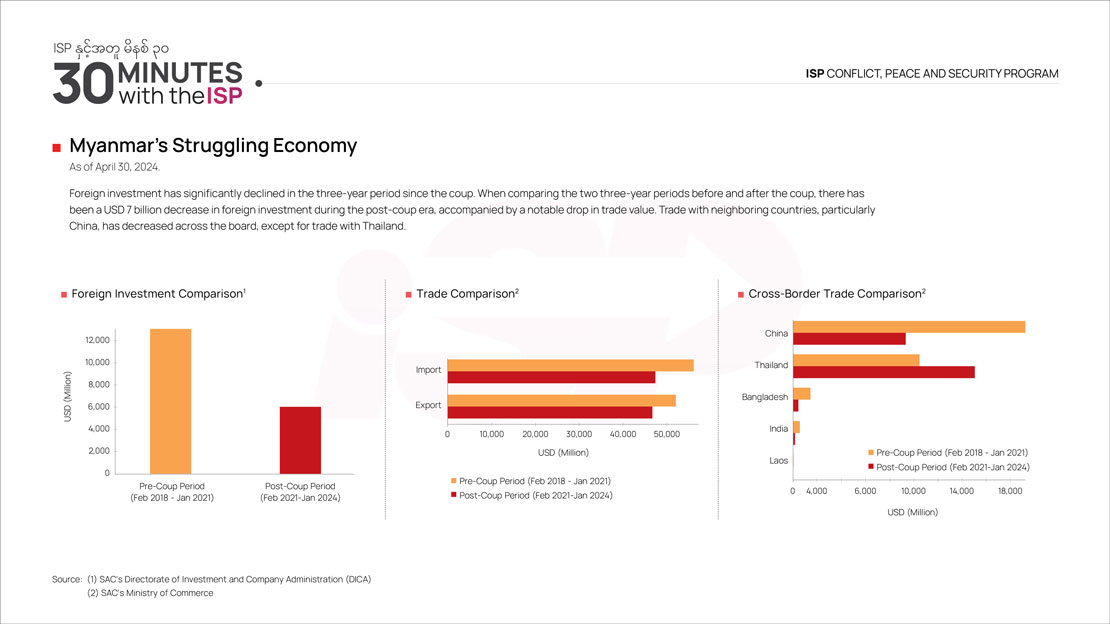

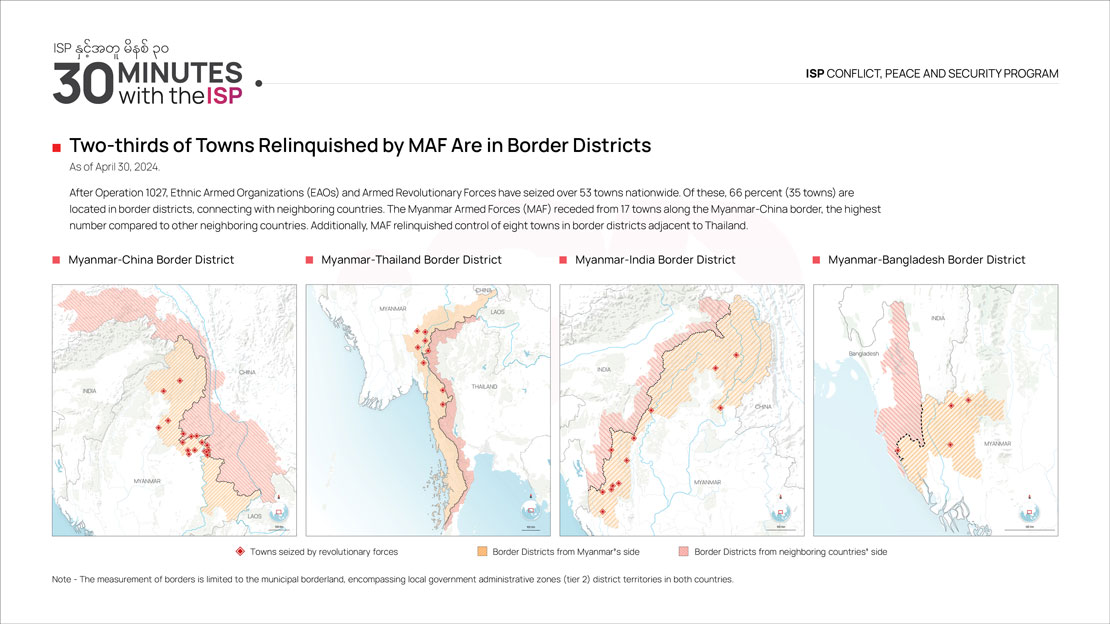

Firstly, I’d like to discuss the decline of the state due to this leadership style. The bureaucratic system, which forms the backbone of the state, has been deteriorating gradually since the coup in 2021. Like it or not, the SAC continues to utilize the remaining state bureaucracy to carry out its functions. However, under the current circumstances, particularly following Operation 1027, the operations of the state apparatus have ultimately diminished. This includes the functioning of police stations and General Administration Department (GAD) offices, and the provision of essential public services such as water, electricity, and government employee salaries, have come to a complete standstill in certain townships. This is evident in the presented figures based on our research data. These figures indicate the weakening functions of the state and the diminishing sovereignty of the state within society. You can look at the data presented.

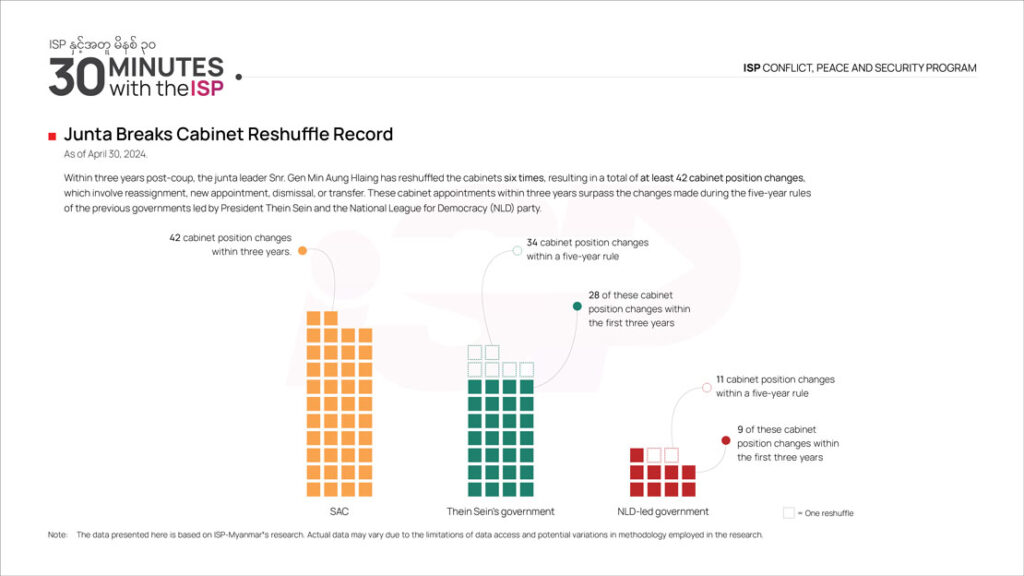

On the other hand, this leadership style is debilitating the regime and its supporting institutions. The MAF cannot address the expanding armed resistance across the country through military means. In addition, the MAF is facing an unprecedented crisis in its history and grappling with humiliation and defeat. In particular, the military outposts once proudly defended have now been relinquished, marking an overwhelming humiliation for the MAF. So, resolving these worsening issues from a political standpoint has become almost impossible, especially within the 2008 Constitutional framework, a framework they staunchly hold on to. When we look at the “leadership” of the regime leader, he struggled greatly during these three years. He tries to drive his power and policies in an ad hoc and expedient manner.

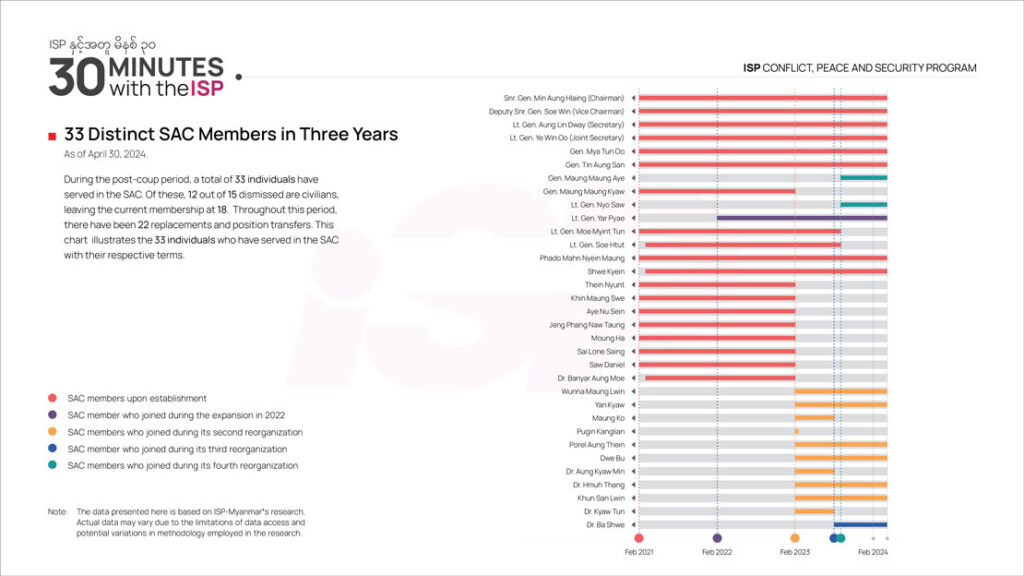

As shown on the screen, the constant transferring, appointing, terminating, and retiring of many of the top leadership positions within the past three years resulted in a total of 153 individuals involved. What these changes signify is that the SAC cannot even maintain basic stability within its own regime, which is fundamental for any administration. When compared to previous governments, the level of reshuffling and the resulting numbers are truly unprecedented and absurd.

At the same time, it seems that the junta leader is out of touch with reality or cannot accept the situation. For example, our research revealed that during meetings, when subordinates report to the junta, they often use phrases like “the current situation on the ground, etc., etc.,”. However, the junta leader would angrily retort, “What’s wrong with the current situation?” Additionally, we noticed that more and more officers within the MAF also seem to view the leadership problem as the main source of the entire crisis. Many current and former MAF leaders assume that the 2021 coup was unnecessary for MAF’s institutional interests, since it has already enjoyed all privileges under the 2008 Constitution. Even if a coup is launched, they hold the view that MAF should be able to restore stability effectively, as found in our research. This shows the increasing discontent towards the junta leader among the rest of the leadership.

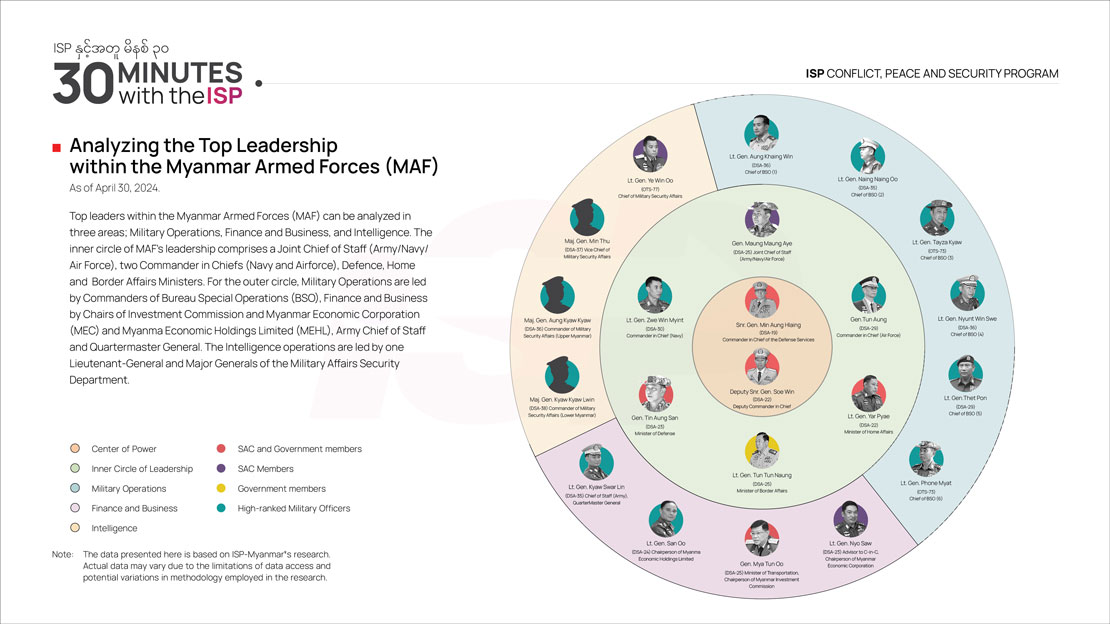

Moreover, it appears that rather than the political leadership of the MAF led by the SAC, it seems more like the junta leader is building his personal power and excessively using compartmentalized governance systems. This concentration of power led to discontent and worry among other leaders. As you can see in the slide, we can clearly see how he has constructed his personal power. In summary, this leadership style has not only devastated the country but also severely weakened the MAF as an institution. These are the four hollowed-out factors within the Naypyitaw throne’s superstructure we’d like to present. Miss Saung Yanant will discuss the second part.

The second part of the discussion will focus on three pillars that had strengthened the Naypyitaw throne’s prolonged existence of the regime. However, the current condition can be best described as they are in the state of “corrosion of pillars.” This can be seen in the second layer in the figure presented.

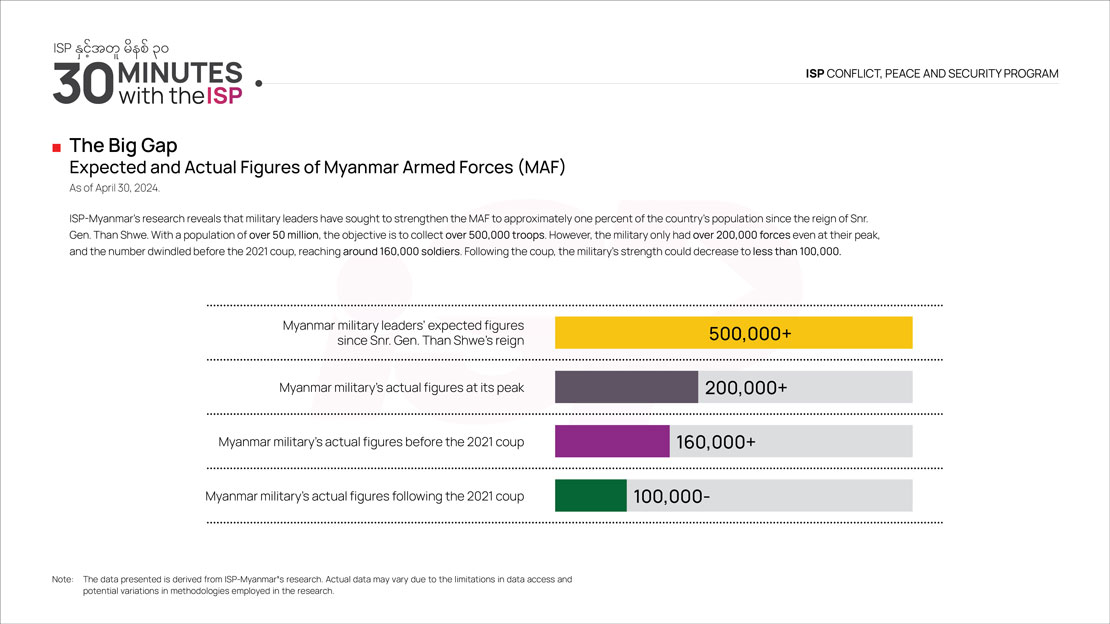

The first pillar is the authoritarian regimes’ quest for public support which often hinges on promoting specific ideologies, ethnic affiliations, and religious convictions. The MAF, for instance, has long portrayed itself as the guardian and defender of people and religion, in particular Bamar nationalism and Buddhism. Previous successive Myanmar junta leaders employed the same techniques and historically it has been effective. But the current conditions suggest the MAF is nullifying the values, like three national responsibilities of the institution, it has set. Even staunch supporters of the MAF’s ideals have publicly voiced discontent with the current junta leader, advocating for his removal and demotion. This suggests that the MAF’s traditional tactics are falling short of their intended goals, the remedy may be still effective, but may not be under this leadership. Another example is to look at the strength of MAF, which is weakening and it seems difficult to get new recruitment. Therefore, as a last resort, the SAC enforced “the conscription law for public service”. This is the evidence of MAF’s failure to maintain its customary ideological sway.

The second aspect I’d like to delve into is the political economy landscape, which is often a crony capitalism. Resort to crony capitalism to consolidate power and wealth, fostering a network of vested interests tied to the rise of the rich who can bolster the economy and ensure allegiance? Myanmar’s military generals successively implemented this strategy. Fostering a mutual support system among vested interests to maintain power is a well-established knowledge and practices of the Myanmar generals who do not need to go to schools to learn this corrupt modus operandi. However, under the current junta leader, even the business community started to grumble, showing dismay, and many often complain that the current situation makes it impossible to do business.

On the other hand, alongside the incumbent crony business circles connected through the military leader’s close associates, the influence of modern-educated young cronies, who are now being introduced through the MAF leader’s children, is increasing. However, these emerging cronies are working neither for the people nor the nation, their businesses seem solely to prioritize their personal profit. Moreover, internal divisions among top MAF officers grow, as conflict arises over the share of profit. Thus, this regime cannot even properly manage the crony capitalism system as employed by past military regimes.

The final pillar to consider is geopolitical support. Historically, juntas convinced the regional powers that the notion of “neighboring countries should maintain ties with Naypyitaw at the very least.” They had also sought diplomatic protection from various quarters, shifting between ASEAN, China, and Russia. However, the current geopolitical scenario showed only limited support from powerful neighboring countries. Even China has reportedly said that Naypyitaw should change to a new playbook with a new face. The Thai PM also publicly stated that the MAF is “losing some strength.” As you can see in the current slide, the SAC’s control is losing along the border.

Regional countries see the Myanmar problem as a messy and complex one. These examples show that some countries outside of the ASEAN, especially China and India who respectively have vested interests in Myanmar, no longer consider SAC as their sole security partner. This means that the junta leader has no ability to evaluate the geopolitical conditions and apply them. Former PM of Cambodia, Hun Sen, once said, “The plough cannot move without the effort of the cattle.” The tools that once served the previous juntas well are now corroding under the control of the current junta leader.

So, we just discussed the decay within the center of Naypyitaw’s throne and the corrosion of its pillar. Mr. Kyaw Htet will be sharing some insights on the current political climate.

In short, Naypyitaw is unlikely to emerge from the current crisis unscathed. Status-quo is no longer an option. The MAF no longer has an advantage in the security sector. A question arises regarding the security sector, whether the MAF will make it out alive without fundamental security sector reforms. To answer this question, a comprehension of Naypyitaw is necessary. As discussed earlier, the hollowed-out conditions within the state, regime, institutions, and leadership must be understood. In addition, to comprehend the support of these four superstructures, it is necessary to conduct research on the corrosive nature of the three pillars that shore up the juntasuch as racial domination ideologies, crony capitalism, and geopolitics with the neighboring nations, as Miss Saung Yanant just discussed.

The final layer that we need to discuss is the political climate. It’s important to keep in mind that we must factor in a political climate where the MAF has virtually lost the entire public support. If we discuss “political climate,” we can see the responses of the public based on their involvement in armed resistance or non-violent non-cooperation movements against the MAF, it is evident that the SAC is confronting a turbulent political climate in Naypyitaw. With this, we’d like to conclude our initial presentation.

Many thanks to the panelists, Mr. Kyaw Htet and Miss Saung Yanant for your discussions. Now, we’d like to continue the Q & A session. The panelists will first answer the questions sent in advance via email by Gabyin members. We have combined questions on similar topics and prepared three questions.

The first question here asks, “The MAF is currently experiencing a crisis and appears to be losing. Does this mean the resistance forces can take advantage or win?”

Thank you for the question. The MAF is losing its military force and influence of authority. Basically, this implies that “the common enemy is weakening” for the resistance forces. At the same time, there are many newly emerged armed groups and shifting conditions of existing EAOs, especially since there are plenty of differences in their political aspirations. As much as they share a “common enemy”, which is now weakened, it is unsure whether these groups share a “common political objective”. This uncertainty has many consequences for the nation’s political conflict. While it is true that the “common enemy” is losing strength, I’d like to say that we are at a stage where the root cause of this country’s crisis is the lack of consensus on a path forward, which is rooted in the original problem, the problem of incomplete nation-building, that we have always been discussing.

Thank you, Mr. Kyaw Htet, for your insightful answer. The second question asks, “I would like to know if the SAC could use the election as a political exit and find a solution at a time when their armed forces are losing strength.”

If we look back, the junta has claimed that they staged a coup because of election irregularities. Then, the SAC’s thinking could be an election as an exit from this mess. Actually, the junta is confronting the turbulent political climate, and the public is opposing them. The public feels outraged that the military rejected their previous election results and again, organizing another election would be negating their will again. This is a remarkable condition where the public no longer wants or is unwilling to accept the existence of the MAF.

This is an institutional challenge for the MAF, not just their leadership as a ruler, but as an institution. Even if an election were to take place in the current situation, it would not be free and fair, even if the elections were organized in their controlled areas. The international community will find it hard to accept it. Therefore, I’d like to answer that the election as a political resolution is not possible at this time.

Thank you Miss Saung Yanant for your answer. The third question asks “Is it feasible to establish a federal army that is frequently mentioned by the resistance forces?”

The establishment of a federal army is conceptually controversial, I think there is a lot to be considered. In theory, prior to forming a federal army, the nation’s formation must be in federalism.

Meaning a federal army is instituted in a federal country. But it is not the same as the MAF. The federal army must be a professional military that does not intervene in politics and politically conforms with a federal constitution that all parties adopt in consensus. I see two parts in forming. The first part is a political agreement which can be linked to what Mr. Kyaw Htet discussed, “common political objective.” Unless the various armed groups that emerged following the 2021 coup can come to an agreement on security sector reforms and political positions, the endeavor to build a federal army will remain akin to building castles in the air.

The second part is how to design the rest of the security sectors and the federal army. If armed resistance forces from different townships, states, and regions were not systematically reformed in the security sector, a federal army is nearly impossible in practice. Therefore, the establishment really depends on political agreement as well as security sector reforms.

We will now be taking one question and one remark from each of our Gabyin members who are attending the event. If you’d like to ask a question or make a remark, please use the raise hand button. We will be inviting the first two attendees who have raised their hands.

What I want to ask is that I am satisfied with the analysis and I have gained more knowledge. The data-based analysis is very good. What I am interested to know is how we can prepare for the situations that might happen beyond (the parameter of) these events. What kinds of analysis do we need to do in advance? What kinds of preparations do we need to make from these analyses? Thank you.

Thank you for your question. This question is very important. In the current situation, we believe that conducting situational analysis is very important. Many have been doing this, and we view that it is necessary. This ISP talk show is also an initiative to fill in this gap. That is the first step. And once we know the reality of the current condition, we need to proceed with what we should do? We think, as we just discussed, whether to move towards federal democracy or a federal army, which we all aspire to, we definitely need a common political agreement. As we mentioned in our first question, it is true that the common enemy has been weakened in our country, but that does not necessarily mean that we’ve got a common political agreement. We have enough data and analysis for this argument. So, we want to encourage all people of this country to urgently discuss how we should find a common political vision and what we should do to reach this vision.

Thank you Mr. Kyaw Htet. Next, we want to invite a comment. If there is another hand raised, we’d like to invite him or her to give a comment.

My question is related to everyone, and I believe it is related to today’s topic as well. The question is about the Naypyitaw problem, the problem of the shifts in Naypyitaw, and the consensus problem to reach the federal democracy. Covering all these questions, my question is “Is today’s problem a de facto problem or a de jure problem?”

Thank you for the question. Due to the limited time for questions, we will respond to this question later in our Gabyin email.

Thank you to all our Gabyin members for your questions. As we finish our Q&A session, we’d like to conclude our show. Do the panelists have any closing remarks?

As I discussed earlier, four superstructures of Naypyitaw’s condition and the throne are hollowed out,and the three pillars supporting the throne are becoming corrosive. At the same time, the SAC is facing a political storm of the public’s response against its rule in Naypyitaw. I’d like to conclude my remarks by highlighting these conditions.

Well. We have some questions unanswered today due to time limitations, and we will respond to them later in our email. Special thanks to all Gabyin community members for attending this event as we conclude today’s event.

Appendix

This appendix includes responses to the questions which we could not answer during the event. These are the questions we collected in advance of the event and the questions received via chat and Q&A buttons during the event.

My question is related to everyone, and I believe it is related to today’s topic as well. The question is about the Naypyitaw problem, the problem of the shifts in Naypyitaw, and the consensus problem to reach the federal democracy. Covering all these questions, my question is “Is today’s problem a de facto problem or a de jure problem?”

This question can be examined using the framework discussed during the event. The SAC is evidently facing a de facto problem, indicated by the MAF’s military relinquishments, the deterioration of its hard power, its unstable position, and the diminishing size of the common enemy for the resistance forces. On the other hand, the lack of a common political agreement, the challenge of legitimacy, and, in particular, the need for a new nation-building covenant indicate a de jure issue.

What do panelists think about the future of Myanmar’s Commander-In-Chief? Will he flee to another country? Will he die on the battlefield? Or will he surrender and be executed by the ICJ? Which category is the best or most favorable outcome in the near future, and which factors are key decisive points to that question? Alternative: What should people do and act to continue fighting against the State Administration Council and Myanmar Armed Forces? Thanks a lot.

When discussing dictators, a common differentiation is made about their exit, whether dead or alive. Looking at the events in Myanmar, it seems neighboring countries encourage a change in leadership. As time passes, leadership issues have led to increased instability and suffering in the country. Overcoming this stormy political climate is becoming increasingly difficult. Although it’s difficult to predict the outcome, how the junta leader survives the storm (dead or alive) largely depends on him.

The data and analysis are excellent. In every process, there are usually some predictable patterns. Among them, it is also important to have a hypothesis and anticipate completely unexpected events. How should we proactively analyze and prepare for such scenarios, for example, having Plan A, Plans B or C? Thank you.

This question is very thought-provoking. When we conduct research and draw conclusions, there is one thing we often say. Despite defining variables and studying their relationships in our research and predictions, it is important to remember that perceptions and realities often differ. Even now, although we predict and analyze based on our data, sometimes unforeseen events, like the Black Swan Effect, can occur. Instead of trying to predict these events, I believe it is crucial to develop a habit of intentionally considering these possibilities when planning our actions and operations.