On Point No. 14

(This article is a translation of the original Burmese language version that ISP-Myanmar posted on its Facebook page on May 06, 2023.)

∎ Events

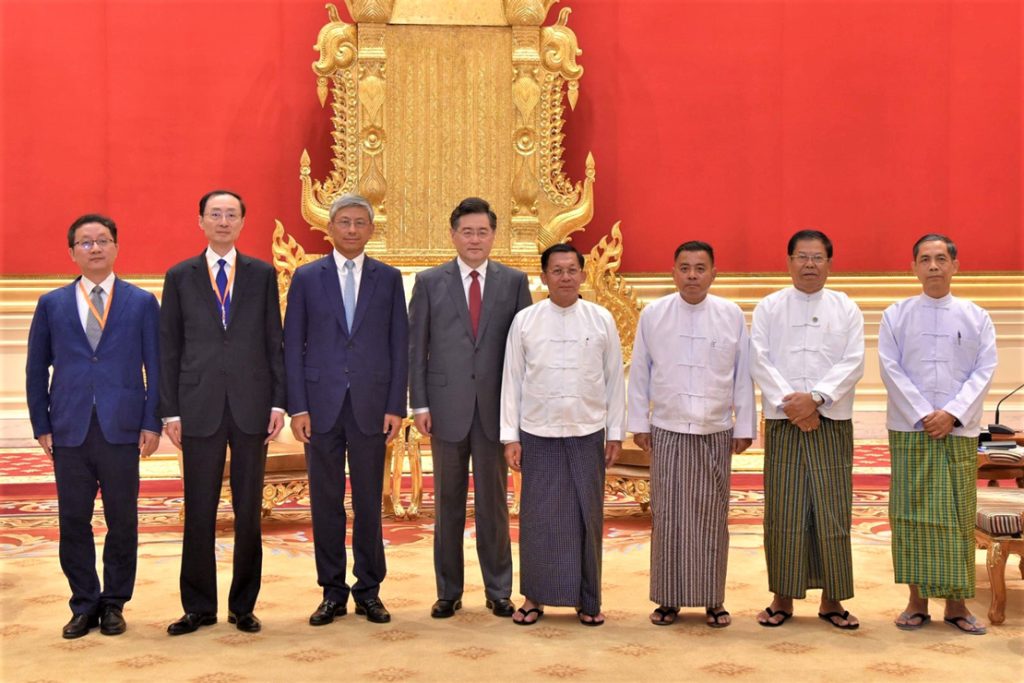

China’s new Foreign Minister Mr. Qin Gang visited Naypyitaw on May 2, 2023. This marked the first official visit by a high-ranking Chinese official to Myanmar’s capital in the two years since the military coup. In the hours prior to the Naypyitaw trip, Mr. Qin toured the border regions of Yunnan province, which maintains vested interests with Myanmar in various sectors. Prior to Mr. Qin’s trip, Mr. Peng Xiubin, Director-General of the International Liaison Department of the Communist Party of China and other high officials from Yunnan had frequently visited Myanmar.

∎ Preliminary analysis

Recently, senior Chinese officials have been visiting Myanmar more frequently, signaling a major policy reset towards bilateral relations. China appears to have abandoned its previous approach to Myanmar which had still maintained a pretence of waiting to see if Daw Aung San Suu Kyi would be released, pushing for dialogue to remain within the framework of the existing constitution, and not abandoning the possibility for the National League for Democracy (NLD) to be retabulated.

China’s new, more pragmatic, approach to Myanmar could be circumvented if new and speedy elections were to be held, providing a political exit from the Myanmar crisis. While Myanmar’s internal security situation continues to deteriorate, China is well-positioned to mitigate any potential negative impacts on its investments in Myanmar. In the past two years, China has been deepening its security relation with certain ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), particularly those EAOs in northern Myanmar. These groups are often described as being closely associated with China.

China has been actively working to advance its economic interests in Myanmar through a range of strategic projects. Diplomatically, China has successfully pushed for an ‘ASEAN-Centrality’ solution to the country’s ongoing crisis, rather than advocating for the internationalization of the Myanmar conflict. This approach allows China to keep the issue within the bounds of regional diplomacy, preserving its influence in the region. China’s current approach to Myanmar’s crisis can be seen as part of its broader ‘Neighborhood Diplomacy’ strategy, which seeks to resolve political conflicts locally, with the help of neighboring countries.

China is closely monitoring both the US’s potential use of Myanmar as a means of containing China, as well as Russia’s growing ties with the Myanmar military. However, China also recognizes that the State Administration Council (SAC) currently lacks the ability to contain the crisis in Myanmar or find a viable solution for its own political exit. In response, China appears to be working behind the scenes to enlist the support of influential figures like former senior leader U Than Shwe to push for a resolution that aligns with China’s interests.

At the outset of the coup, China primarily advocated for the junta to preserve existing Chinese projects in Myanmar that had been agreed with the previous NLD government, an approach which seemed to still center on Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. However the SAC has not only refused to allow her to meet with foreign diplomats but has also sentenced her to lengthy prison term. Recently, the junta has also revoked the official status of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s NLD political party. China has faced the military junta’s tough and uncompromising actions, and has since maintained a low profile on the issue to mitigate potential risks to its economic interests or its diplomatic standing. To avert diplomatic criticism, China has agreed to the continuation of the UN term of NLD envoy U Kyaw Moe Tun as Myanmar’s country representative, and has mostly refrained from taking a public stance on the Myanmar crisis in the UN Security Council or ASEAN forums.

China has largely taken a hands-off approach to the situation in Myanmar if it has not directly impacted its fundamental interests. China has frozen the Myanmar crisis agenda in international diplomacy and refrained from direct intervention. At the same time, China has used its influence with EAOs near its border to prevent armed conflicts from escalating and posing a threat to its strategic projects and broader geopolitical interests. (See ISP Mapping No. 8)

China has instead focused on cracking down on cross-border crimes. China has particularly emphasized a ‘containment policy’ for Chinese strategic interests in Northern Shan State, aiming to limit the growth of the People Defense Forces (PDFs), which have been supported by EAOs in Northern Shan State, ensuring no fighting takes place close to the Chinese border, and restricting PDF activities from impacting Chinese interests. China’s special envoy to ASEAN, Mr. Deng Xijun, has been involved in initiatives with both the SAC and the most powerful EAOs in Nothern Shan State known as the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee (FPNCC). The recent statement of the FPNCC dated March 16 expressed welcome and support for China’s mediation efforts to end internal conflicts in Myanmar. (See ISP Explainer No. 1)

China has thoroughly analyzed the various stakeholders involved in Myanmar’s conflict, including their organizational structure, strength, aspirations, and backgrounds, and can use structural constraints to protect its interests. With Chinese involvement, a prospective peace deal between the EAOs in Northern Shan State and the SAC could see emerging PDFs weakened by ensuring a separation of ties to these EAOs.

China has managed to effectively decouple its interests from the emerging conflict in Myanmar since the coup, and has continued to execute strategic plans in the country, including land, sea, and cross-border transportation networks to industrial zones. With the plannings to pursue its strategic interests all set, China has increased the frequency of its diplomatic visits to Myanmar.

If the junta continues to prolong its rule though, the conflict in Myanmar could worsen and become a geopolitical hotspot which could attract more international actors, a scenario China would want to avoid. China seems particularly worried that the SAC continuously extends its emergency powers, avoids announcing any details on the promise of election dates, and has seemingly lost sight of any political exit strategy. The SAC’s prolonged and haphazard rule is impeding the development of the entire nation.

It appears that China is in favor of Myanmar holding an election to stabilize the country, prevent excessive involvement from the West, and collaborate with China so that Myanmar can focus on China’s style of development. This may be why Chinese officials met with former senior leader U Than Shwe, who introduced a political transition in 2010 with the idea of ‘hegemonic party regime’. China may be closer to Than Shwe’s idea of ‘hegemonic party regime’, as Mr. Peng Xiubin, Director-General of the International Liaison Department of the Communist Party of China first met him prior to the Chinese Foreign Minister’s visit. This fact could suggest that China is becoming impatient with the present SAC rule. China has already laid the groundwork and is about to expand its larger geopolitical and economic plan, However the continuation of military rule in Myanmar is increasingly becoming an obstacle. This suggests that China may wish to transform the political setting in Myanmar through new elections, as U Than Shwe did before, and deploy all available stakeholders’ influence to push towards its major policy reset.

China had previously supported ASEAN’s efforts to resolve the Myanmar crisis, but it now appears to be promoting a new form of ‘Neighborhood Diplomacy’ led by China itself. China can pursue this new approach either through bilateral dialogue or a take multilateral approach involving countries neighboring Myanmar. China may also seek to gather support through informal Track 1.5 meetings and closer cooperation with Thailand, which is the frontline country in dealing with Myanmar’s crisis. If China’s ‘Neighborhood Diplomacy’ approach were successful, it could gradually diminish ASEAN’s role in Myanmar, and also limit the role of the West, particularly the United States.

∎ Scenario forecast

China’s recent effort towards resolving Myanmar’s crisis can be seen as a fresh approach to their ‘Neighborhood Diplomacy’. This introduces a new diplomatic layer alongside the pre-existing West-led policy and ASEAN-led initiative, as Myanmar’s situation remains unresolved. The new China initiative can be analyzed as giving a ‘second chance’ to the Myanmar military junta to find a way out of the crisis. China may become more involved in ‘Track 1.5 meetings’ either behind the scenes or more visibly leading the initiative.

China’s intention is partially believed to be a response to the US’s National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), in particular the Burma-focused chapters. However China could also be attempting to resettle the balance of power with Russia, which has been increasingly boosting its ties with Myanmar. China could use these Track 1.5 meetings to persuade other parties to endorse Myanmar’s new elections, as well as to provide much-needed humanitarian assistance, an approach which yet to be successful.

China’s interest in its ‘Neighborhood Diplomacy’ in Myanmar could lead to a quick conclusion of new Myanmar elections, preventing the further deterioration of the internal security situation (through various means including encouraging a ceasefire), capturing and controlling the Myanmar agenda in international diplomacy, and commissioning Myanmar into an economic hub in a ‘Grand Opening’ of post-Covid pandemic China. Despite international pressure, Myanmar’s successive military and civilian governments have historically resisted external influence. This is evident from their handling of issues like the Myitsone dam and the Rohingya crisis. While the involvement of other countries and organizations like the UN and ASEAN can be supportive of change, none of them hold significant leverage over Myanmar, except for China and the US using coercive diplomacy. However it remains important not to overestimate the potential outcomes of external power being a force for change in Myanmar.