(The original Burmese version was published on the Facebook page of ISP-Myanmar on March 8, 2021.)

Since the coup d’état by the Myanmar military on February 1, 2021, there have been mass protests against injustice across the country. Women protesters of various ages and different social strata have played a leading role in the protest movement with adolescent women playing an active part in frontline activities. In the face of violent crackdowns by the military and riot police, women protesters did not retreat and kept pace with male protesters. In commemoration of International Women’s Day and in recognition of the role played by women in protests against the military coup, the fourth issue of ISP-Myanmar’s What Matters series focuses on the issue of discrimination against women.

∎ Executive summary

The conservative concept of gender roles is irrelevant in understanding political movements which concern the entire country. Conservative views of gender roles – the public/private dichotomy – suggest that women’s roles are limited to issues related to household duties (private), and that only men should deal with issues related to politics (public). These often deep-rooted views about women’s roles limit their ability to exercise basic rights. Gender experts, like Carole Pateman (1983), argue that the idea of a gender-based public/private dichotomy is an incorrect and misleading concept, which women rights activists have fought against for centuries. The recent experience of political movements in many countries shows that this concept of gender-based discrimination is erroneous and outdated.

∎ Why does it matter?

There have been instances of housewives participating in political movements through their daily routines, such as taking care of home altars and shrines and kitchen chores. One example is the participation of Taiwanese women in the 2014 “Sunflower Movement”. The mass movement began with the protests against the Cross-Strait Services Trade Agreement (CSSTA), a trade agreement between Taiwan and mainland China. Then, it transformed into a mass movement against the construction of a nuclear power plant in Taiwan. A study by Taiwanese sociologist Chia-Ling Yang on the “Sunflower Movement” suggests that it is incorrect to view housewives as only concerned with housework and with little chance for participation in politics. Taiwanese housewives took part in this mass movements through their activities of daily living as citizens and mothers.

One housewife in Chia-Ling Yang’s study noted,

being a mother is our job, but in fact we mothers can participate in politics as our second job. We know by heart what children want – what the world needs – and we are not like those politicians who only listen to their political party and care about their own gain. […] I think mothers are those who are stubborn about making the world better. (Yang, 2017, p. 665)

Being a mother is our job, but in fact we mothers can participate in politics as our second job. We know by heart what children want – what the world needs – and we are not like those politicians who only listen to their political party and care about their own gain. […] I think mothers are those who are stubborn about making the world better. (Yang, 2017, p. 665)

In this case, Taiwanese women showed the important roles of mothers and housewives in mass movements by participating in public readings of anti-nuclear children’s books.

Women-led mass movements took place not only in Taiwan but also in Thailand in the same year. Thai women were also in the frontlines of the mass protests against the 2014 military coup d’état. The protesters put forth numerous political as well as women’s rights related demands, such as calling for the resignation of Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha, the promulgation of a democratic constitution, reforms of the Thai monarchy, support for reproductive rights, lower taxes for feminine hygiene products, and ending rules oppressing women in schools.

Recently, women in Belarus were in the frontlines of protests against the violent crackdown ordered by President Aleksandr G. Lukashenko. The dictator is notorious for his belief in male dominance and faced protests for his electoral fraud in the September 2020 elections.

∎ Is it relevant for Myanmar?

As women participate in various political movements around the world, such as the “Sunflower Movement” in Taiwan, the rejection of the gender-based public/private dichotomy is also relevant to Myanmar. In Myanmar, women from all walks of life participate in the anti-coup demonstrations through various forms of protest. There are women who joined marches to voice their political demands. Whereas, there are also women who participated in peaceful sit-in protests in the streets, while doing daily activities such as chanting Buddhist prayers, knitting sweaters, and doing face makeup for themselves and other demonstrators. At that time, the people identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender also participated in the protest marches in colorful attire.

Moreover, women continue to be earnest participants in the “Metal Drumming Campaign,” in which people bang tin boxes, pots, and pans every evening at 8pm as a form of protest against the military coup. Furthermore, women hung their skirts and underwear over the entryways to residential streets as part of efforts to deter state security forces from entering to attack peaceful protesters. The hanging of undergarments plays on the superstitious beliefs among male security forces that passing under women’s skirts and underwear lowers their hpon, which is a Burmese concept for spiritual glory or power often associated with masculinity.

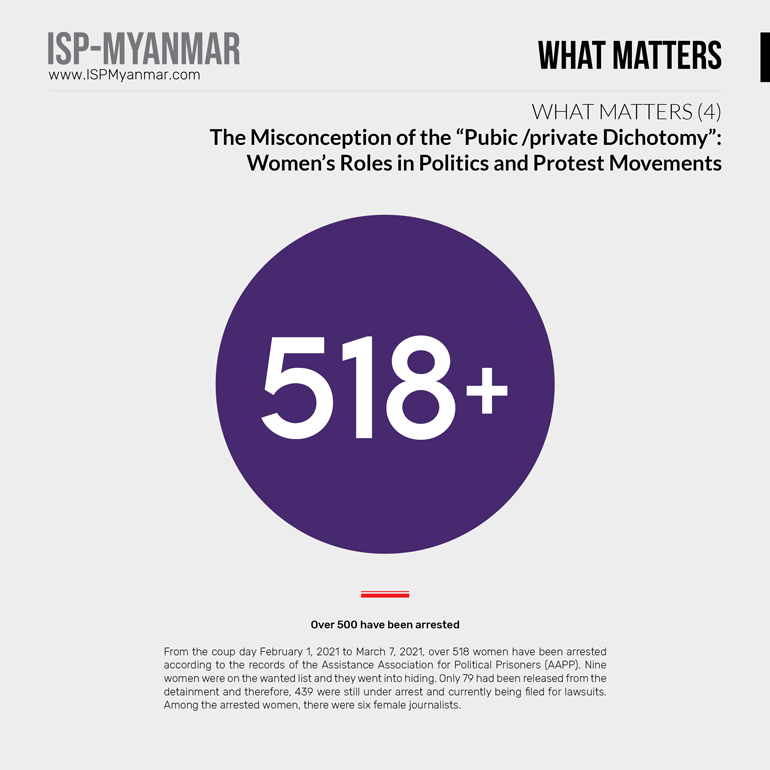

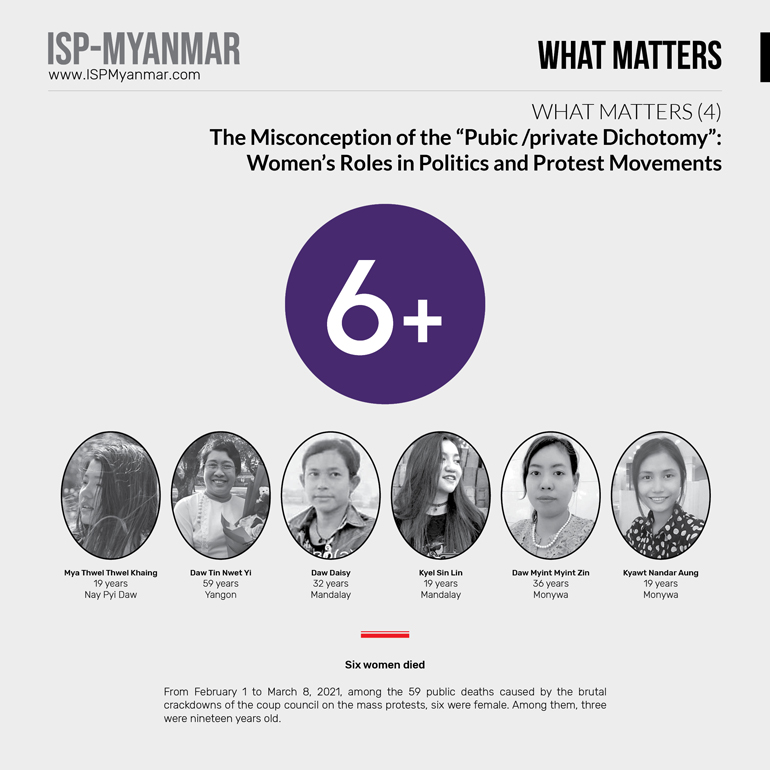

Women also play key roles at the forefront of protests against the junta’s forceful attempt to appoint ward administrators. As mentioned above, women are at the forefront of the peaceful protests against the coup d’état and display other forms of leadership. Even when the junta has cracked down on protests, women have not retreated from their participation. The first victim of the military’s violent crackdown was a teenage girl, and by March 8, 2021, six of the 59 deaths caused by state security forces against protestors were women.

In the mass movement against the male-dominated military dictatorship, women have demonstrated their active involvement in politics through their daily activities. The involvement of women in Myanmar’s anti-coup movement has changed conservative perceptions about gender roles. Because of women’s participation, people have begun changing their thinking that politics is an issue only for men and has nothing to do with women to one in which politics involves women and issues related to their daily household activities. With this change in public thinking, there could be more opportunities for Myanmar women to exercise their rights to participate in politics in the years to come.

∎ Further Readings

Carole Pateman.1983. Feminist Critiques of the Public/Private Dichotomy, in S. I. Benn and G. F. Gaus (eds). Public and Private in Social Life (New York: St. Martin Press).

Chia-Ling Yang. 2017. The Political is the Personal: Women’s Participation in Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement, Social Movement Studies, DOI: 10.1080/14742837.2017.1344542

Ivan Nechepurenko. September 19, 2020. Hundreds of Women arrested at protest in Belarus. New York Times.

◉ What Matters ISP-Myanmar covers a section entitled “What Matters” that could benefit the current anti-coup mass movements through a series of research work. This section aims to introduce issues and data that should be addressed in a short, easy-to-read manner and accessible to everyone based on research findings. The introduced facts, cases, and data are intended to be a thought-provoking stimulus, but not as a definite view. The purpose is to make the data presented more accurate and complete. In this series, ISP would try to answer three questions in general: 1) what is the issue of concern? 2) why does it matter? 3) is it relevant for Myanmar? Addressing these questions does not involve an exhaustive examination but covers the relevant elements and claims. Thus, each issue of “What Matters” provides a list of suggested readings and references for further study. In the current situation, this section will focus on research findings related to three research topics. These are: 1) research findings related to coup d’état 2) research findings on mass movements 3) research findings on how the international community (especially powerful foreign countries that can provide significant support ) intervened in military coups and the authoritarian states. The research will be based on comparative studies. Research data collected by local partner organizations will also be requested and respectfully presented in various forms from time to time.