OnPoint No. 7

(This article is a translation of the Burmese language version that ISP-Myanmar posted on its Facebook page on February 1, 2022.)

∎ Event

February 1, 2022, marks the first anniversary of the military coup that reversed Myanmar’s progress toward democratic reform. The junta extended its rule for another six months as the country remains in a state of emergency. Meanwhile, resistance to military rule continues in various forms as calls went out for a countrywide “silent strike” to mark the coup’s first anniversary. Residents of many major cities showed their defiance by joining the strike despite premeditated arrests, restrictions, and threats.

∎ Preliminary analysis

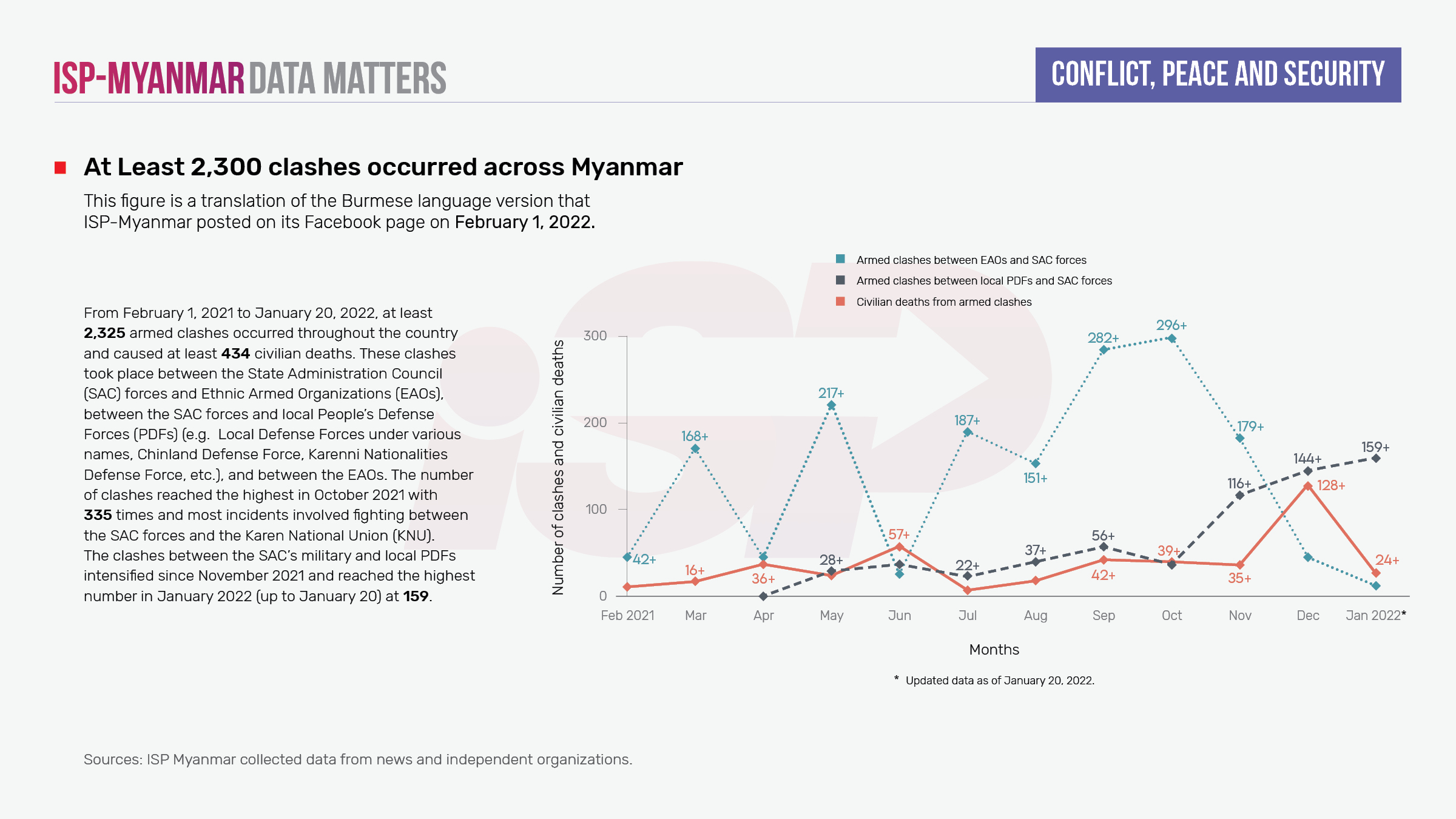

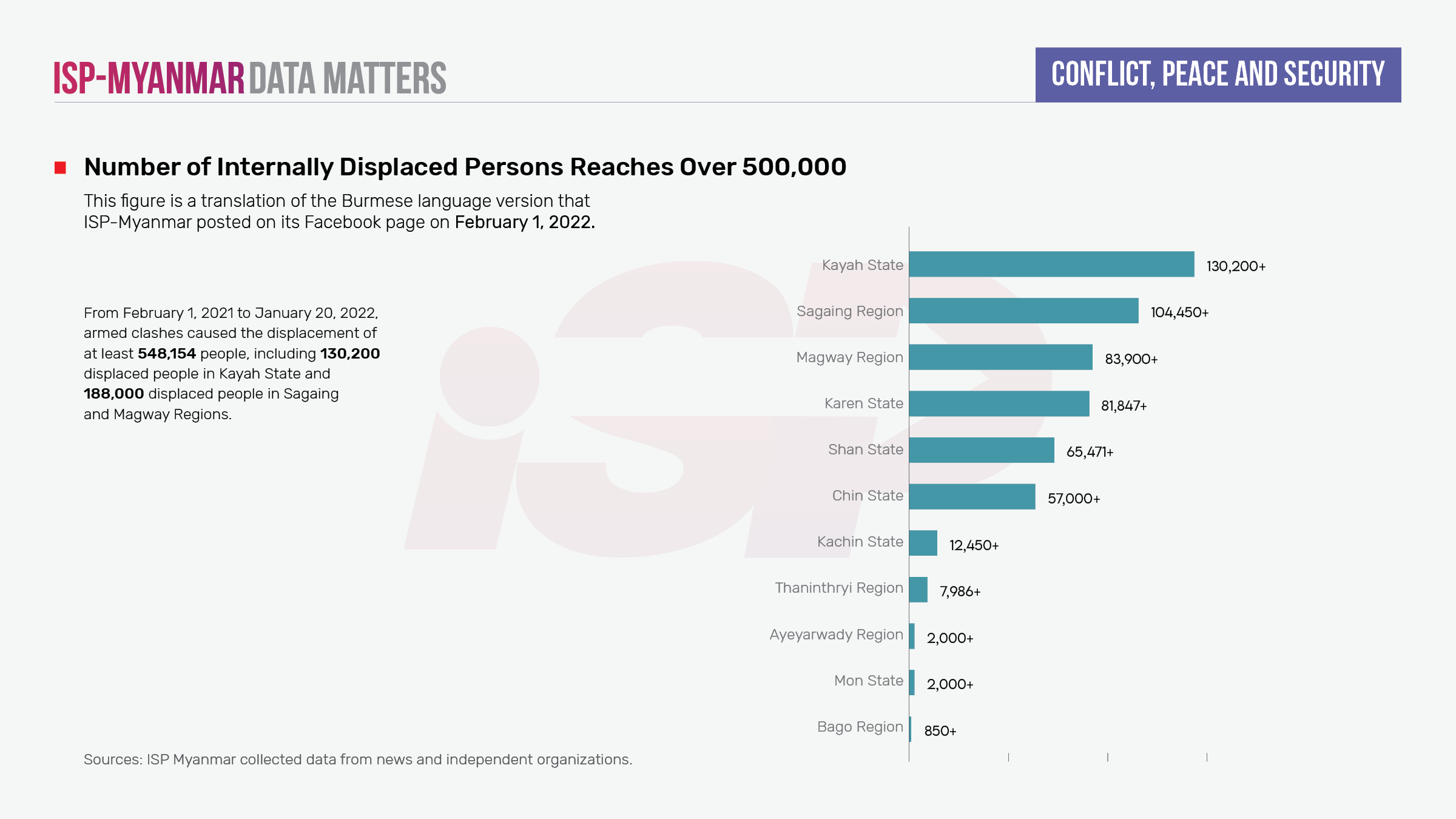

The ruling junta cannot effectively enforce its rule throughout the country, as it continues to face bold defiance in several regions. The country has lost respect in the international community, which has led to tremendous hardships for people’s livelihoods. The arrests and inhumane treatment of dissidents, and a ruthless war against its own people have created humanitarian emergencies. Civilian casualties keep rising, as does the massive number of displaced persons in several parts of the country.

When looking back on the year that followed Myanmar’s military coup, it is useful to consider three important perspectives. The first is how the resistance movement and the junta’s pacification operation against it have made immediate changes to the political landscape of the country. The second is how new players in the conflict have affected the current political situation in the country. Finally, we need to understand how a shift of norms and values has taken place within Myanmar society generally in the aftermath of the coup.

The ruling State Administration Council (SAC) has ignored the desire of the majority of its citizens and continues to impose its rule through rampant human rights violations, including the brutal arrest, ill-treatment and killing of its own people. Moreover, the SAC has failed to effectively implement ASEAN’S Five-Point Plan for resolving the country’s current crisis. Anti-junta forces still remain committed to putting pressure on the junta—including armed struggle—and to “undermine the junta’s effective control” by any and all means.

In terms of the first perspective, those who want to improve the political situation have few options in the short term and must focus on a long-term strategy. Fervent resistance that seeks quick results might risk creating deeper societal rage, growing bitterness, and a destructive “us vs. them” mentality.

With respect to the newest players in Myanmar, the role of groups such as the National Unity Consultative Council (NUCC), National Unity Government (NUG), Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), and local forces including PDFs, LDFs, CDF, PDF, etc., will be crucial to any resolution of political conflicts. The current crisis will not be resolved without considering the role of these new actors, ranging from issues of cooperation in humanitarian assistance to a political settlement. The international community should acknowledge explicitly the role of new conflict actors, even though this might be difficult.

Finally, changes in societal norms within Myanmar following the massive “Spring Revolution” have led many people to actively join political movements and inspired an “all-inclusive” approach—regardless of race, ethnicity, or religion— and a desire to end discrimination in society. Many people have now embraced the idea of ending the old era and the old system.

∎ Scenario forecast

The post-coup situation should be evaluated on the basis of these three proposed perspectives. If dissidents prepare a systematic and long-term strategy, rather than pushing haphazard responses that can only achieve short-term results, they could more effectively realize the political goals to which most people in the country aspire. Provoking “revenge” and anger will only jeopardize the prospect for long-term success.

Myanmar’s new conflict players need the explicit acknowledgement and cooperation of the international community and other key stakeholders. This support could contribute to visible results for conflict transformation. Otherwise, short-term remedial thinking could end up creating new and deeper complications.

Moreover, any effort to change societal norms in Myanmar should not just focus on identifying and opposing a common enemy. Rather, these new norms should promote deep-rooted change for everyone in the country. In the end, society should strive for “shared citizenship” for all.