(The original Burmese version was published on the ISP-Myanmar Facebook page on March 5, 2021.)

∎ Executive Summary

Scholars and researchers alike have long puzzled over whether brutal repression undermines mass uprisings or emboldens even more courage and determination of the popular movements, thereby undercutting the regime’s legitimacy and precipitating the governmental overthrow. Conventional wisdom suggests that brutal repression weakens mass movements. However, as pointed out by social scientist Brian Martin, violent oppression could paradoxically produce backfire effects. Martin examines why some mass movements succeed at making violent repressions backfire and why others did not. At the same time, the author also studies the causes of the backfire. Similarly, Erica Chenoweth (2018), a renowned scholar of social movements, studied 100 nonviolent anti-regime campaigns, including a time-series analysis of 342 events that took place between 1946 to 2006.

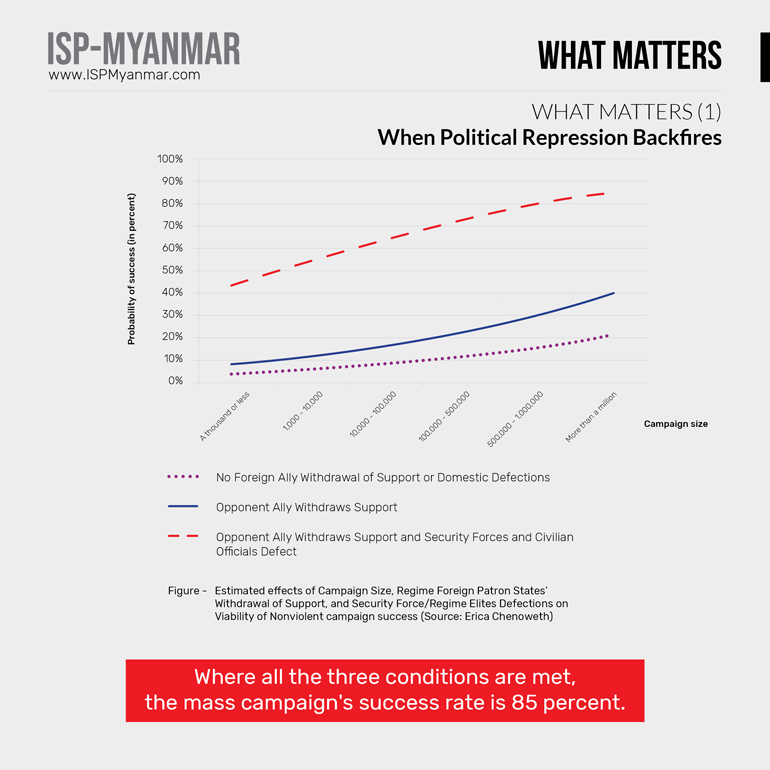

Chenoweth identifies three critical factors that are decisive in causing the violent repressions to backfire. These include 1) sustained campaign participation, in terms of both size and diversity (for instance, the ability to sustain over one million participants and use diverse forms of struggle); 2) loyalty shifts within the regime elites, security forces, and civilian administrators of the government mechanisms; and 3) withdrawal of support from the regime’s powerful foreign patron states which provide political, economic and diplomatic assistance. If all three factors are present, the probability of suppression leading to a backfire is over 85 percent. Even when there are no loyalty shifts among the regime elites, security forces, and civilian leaders, as well as the regime foreign patron states continue their support, the chances of success for a nonviolent campaign is 20 percent, provided that a high degree of campaign participation is sustained (please see the diagram).

∎ Why does it matter?

Chenoweth’s (2018) study of repression-led backfire matters because it draws on earlier protests to provide insightful information on how the three factors mentioned above could be achieved. For example, the study shows no evidence for loyalty shift or the regime loyalists changing sides happened due to the international pressures, international sanctions, and the regimes’ brutal oppressions and crackdowns. The study notes that defections by regime loyalists can take place under this condition: when the mass movements are sustained and become more tactful, and the activities of the movements are known to the wider public and becoming unconcealable (perhaps through the local news, including social media networks) even under the brutal suppression. Likewise, the study also suggests that continuous coverage of massive nonviolent campaigns on international media can lead powerful foreign patron states of the regime to withdraw their support. On the other hand, the study warns that if the foreign patron states of the regime do not see a robust and reliable leadership of the mass movement, they may be hesitant to withdraw their support. The study also highlights that if the popular campaigns are highly disorganized and lack a centralized leading body, the foreign patron states may not be able to identify the actors with whom they may deal in the future and, as a result, making them difficult to shift their support to the people.

Is it relevant to Myanmar?

The study is very relevant to Myanmar. Over a million people have participated in the 2021 mass protests- The Myanmar Spring Revolution – and the protesters have tactfully used a wide variety of methods. These range from the mass banging pots and pans to the mass protests on the roads and streets across the country. However, the movement could be more effective if the protesters could use more variations of tactics. The timely coverage by the international media and social media networks, in particular Facebook, has placed significant pressure on the regime supporters ranging from the Chinese Government to those who are hesitant to change sides toward the people.

However, the pressing issues here include: how would China and ASEAN countries assess whether the Myanmar mass uprising has a centralized leading body; and what are the current

relationships or what dynamics are likely to emerge between these countries and the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), a rival parliament established by the protesters.

One other method widely used in the 2021 Myanmar protests is what the protesters termed “social punishment,” by which individuals shun and penalize those allies with the military regime and civilian officials who do not join the mass Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM). The study does not cover whether previous mass campaigns have used “social punishment,” whether it is effective, and the consequences of employing this kind of punishment. This dynamic could be an important variable for further future research.

The key takeaway of Erica Chenoweth’s research work is to make repressive actions backfire: the most crucial factor is to sustain a high level of campaign participation and use diverse and tactful forms of struggle.

∎ Further readings

Chenoweth, Erica. 2018. “Backfire in Action: Insights from Nonviolent Campaigns from 1946-2006” in Lee Smithey and Lester Kurtz eds. The Paradox of Repression and Nonviolent Social Movements. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Martin, Brian. 2007. Justice Ignited: The Dynamics of Backfire. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

◉ What Matters ISP-Myanmar covers a section entitled “What Matters” that could benefit the current anti-coup mass movements through a series of research work. This section aims to introduce issues and data that should be addressed in a short, easy-to-read manner and accessible to everyone based on research findings. The introduced facts, cases, and data are intended to be a thought-provoking stimulus, but not as a definite view. The purpose is to make the data presented more accurate and complete. In this series, ISP would try to answer three questions in general: 1) what is the issue of concern?; 2) why does it matter? 3) is it relevant for Myanmar? Addressing these questions does not involve an exhaustive examination but covers the relevant elements and claims. Thus, each issue of “What Matters” provides a list of suggested readings and references for further study. In the current situation, this section will focus on research findings related to three research topics. These are: 1) research findings related to coup d’état 2) research findings on mass movements 3) research findings on how the international community (especially powerful foreign countries that can provide significant support ) intervened in military coups and the authoritarian states. The research will be based on comparative studies. Research data collected by local partner organizations will also be requested and respectfully presented in various forms from time to time.