Insight Email No. 25

This Insight Email is published on October 16, 2023, as a translation of the original Burmese language version that ISP-Myanmar sent out to the ISP Gabyin members on October 13, 2023.

In this week’s Insight Email No. 25, ISP-Myanmar focuses on the incident of the Mung Lai Hkyet explosion and what the consequences could be. In addition, it gives an analysis of “the Military’s Succession Crisis” and the widening generation gaps in military leadership. The bulletin also discusses the extreme weather and severe floods in Myanmar brought by El Niño at the beginning of the season: Bago City, for example, encountered the worst recorded incident of flooding in 60 years. Furthermore, a widespread trend of corruption is discussed, along with ISP-Myanmar’s socio-economic survey findings. Last, but not least, the ILO’s Commission of Inquiry report on Myanmar and the future consequences of it are examined.

∎ Key takeaways

1.Huge Explosion in Mung Lai Hkyet IDP Camp

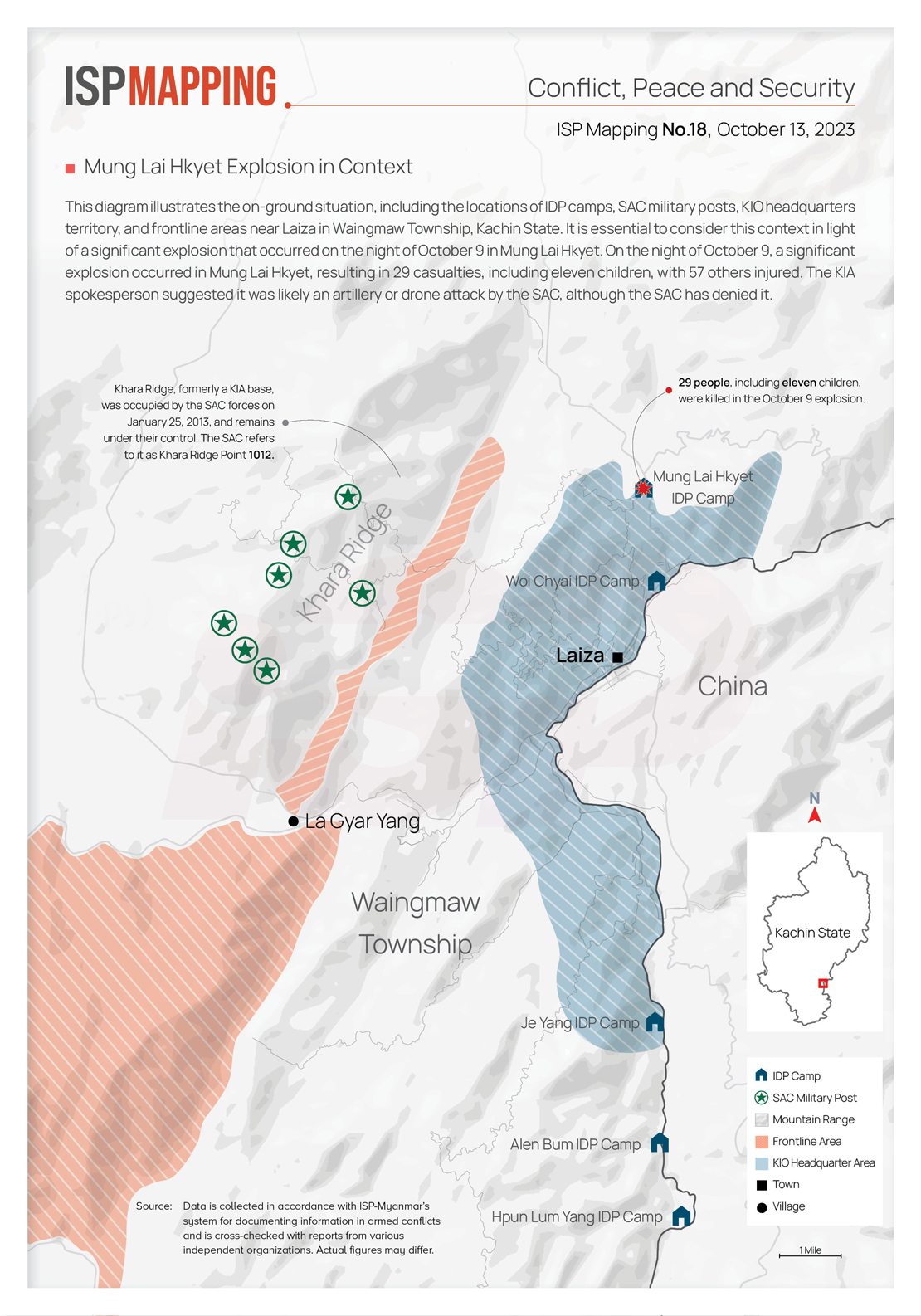

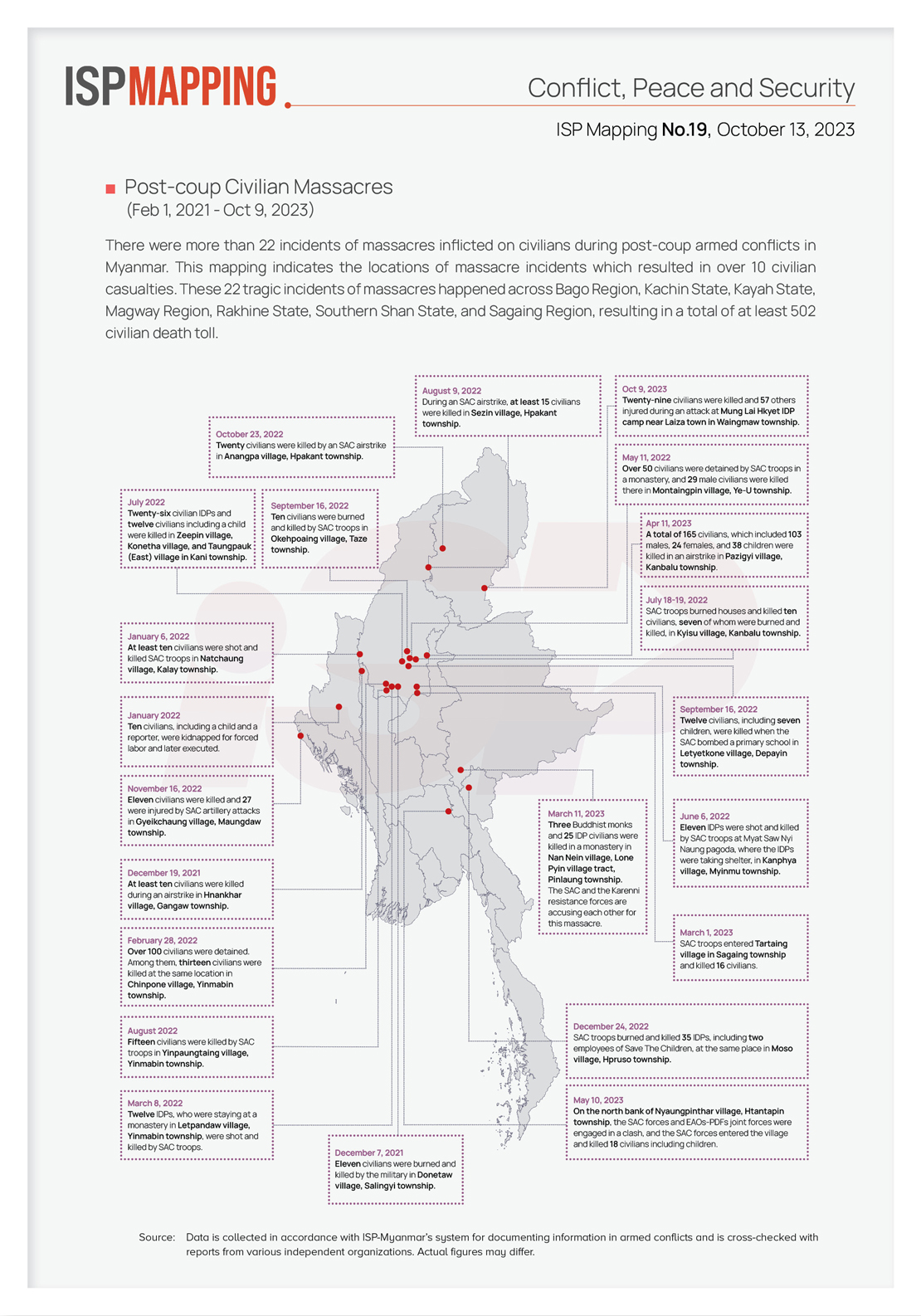

A huge explosion occurred on the night of October 9 in Mung Lai Hkyet, a place close to the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) headquarters on the China–Myanmar border. This is a region of plains between two mountain ranges: “hkyet” means “ravine” in the Kachin language and holds a shelter for many refugees. The bizarre explosion in Mung Lai Hkyet was so severe that a large earthen hole remained at ground zero. The whole Mung Lai Hkyet IDP camp was damaged, and at least 130 families of the 600 displaced persons it houses were evacuated in an emergency. Reports indicate that 29 people, including eleven children, were killed and that 57 others were injured in the explosion.

There are controversies surrounding who committed the October 9 attack. A KIA spokesperson said it was presumably an artillery or drone attack by the State Administration Council(SAC) and is still investigating what type of weapon was used. The SAC’s spokesperson, Maj. Gen. Zaw Min Tun, denied that the deed was committed by the SAC, and explained that it may have been an explosion of stored ammonium nitrate. The KIA rejected this statement.

The BBC Burmese news mentioned on October 10 that the destructive explosion in Mung Lai Hkyet caused all residents living within 300 meters to be killed and injured many outside the 300-meter area. The blast left a large hole in the ground and damaged buildings and vehicles in the surrounding area. The scene is likely to be mentioned as a discarded mine site, BBC reported. Mung Lai Hkyet turned into a bald mountain that seem like bulldozed by machines, causing a village to disappear overnight.

The SAC’s military columns have been attacking KIA forces in Nam Sam Yang village for months since July. Concurrently with the Mung Lai Hkyet explosion, the SAC had fired on the area. On September 28, 2023, the SAC forces shelled places near Mung Lai Hkyet, killing one Arakan Army (AA) officer and injuring another ten. Reportedly, the shells were fired from Khara ridge, situated six miles distance from KIA HQ. Khara ridge was a former post of KIA base and the SAC force occupied in 2013. In another incident, on November 19, 2014, the military fired artillery on KIA’s officer training school, and 23 cadets of KIA’s allied forces were killed. In December 2016, the military shelled Mung Lai Hkyet village and at least 400 refugees were forced to flee.

The consequences of the Mung Lai Hkyet incident may be enormous. Immediately, it will have an impact on the SAC’s preparations for the anniversary of the eight-year Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA), which it is aiming to organize differently than in the past. The incident may have a moral and sentimental impact on invited guests of ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), leaders of political parties, and local and international guests. The incident may fuel distrust and escalate conflicts. If the SAC is sure they were not responsible for the incident, the parties can request an international investigation by China and ASEAN officials. The SAC mentioned that Chinese police are investigating the cause of the explosion while China’s foreign minister only stated that “China is paying close attention to the reports” and “calling on relevant parties to resolve disputes peacefully through dialogue and consultation, avoid escalation of the situation, and take concrete and effective measures to ensure security at the China–Myanmar border.”

2.The Military’s Succession Crisis and Generation Gap

Lt. Gen. Moe Myint Tun, a member of the State Administration Council (SAC), and Brig. Gen. Yan Naung Soe were convicted of many offenses, including high treason and corruption, and sentenced by court martial on October 10, 2023, to suffer transportation for a life sentence, equal to a 20-year term. Until this adjudication, Moe Myint Tun (DSA 30) took charge of the military as chief of staff and presumably, he gained favor with the commander-in-chief, Min Aung Hlaing. He was then poised to become Min’s successor. It is typical to deduce who is going along on the trips with the SAC head and who are among the top brass by observing the standing protocol in the official newspapers.

Much like the synchronized retirements of Snr. Gen. Than Shwe and Deputy Snr. Gen. Maung Aye, if the current Snr. Gen. Min Aung Hlaing and Deputy Snr. Gen. Soe Win retire concurrently, Lt. Gen. Mya Tun Oo (DSA 25), who was serving as the chief of general staff for the army, navy, and air force, was once speculated to be the next commander-in-chief of Myanmar defense services. Reportedly, he was thought to be chosen by former junta leader Than Shwe. Nevertheless, since the 2021 military coup, he became minister of defense and was later transferred to deputy prime minister and minister of transport and communications, an apparent demotion. After the punishment of Moe Myint Tun, Lt. Gen. Mya Tun Oo was assigned to key positions as his replacement. But now he is turning 62 and is therefore less likely to lead the military as commander-in-chief.

When Min Aung Hlaing (DSA 19) was selected for the commander-in-chief, he was a military cadet generation 18–19 years younger than his superiors, Snr. Gen. Than Shwe (OTS 9) and Deputy Snr. Gen. Maung Aye (DSA 1). For that reason, the next commander-in-chief could be chosen from the younger military generation from the Defense Service Academy (DSA), and may end up being someone such as the 30th-batch graduate, Lt. Gen. Moe Myint Tun. Moreover, it is generally thought that the new commander-in-chief should be in their 50s, as he would be able to serve under two terms of government (two terms of five years). Since the prospective Moe Myint Tun was removed from the scene, who will become the next commander-in-chief for the Myanmar military is still being speculated about. Some military analysts anticipate he could be the rapidly rising Lt. Gen. Kyaw Swa Lin (born 1971, present age: 52) (DSA 35), the present quartermaster general of the defense services. He was popular when he was commanding the Central Military Command in Mandalay with the rank of brigadier general. In 2020, he was promoted to lieutenant general and became the youngest in that position in Myanmar’s army. Though he is taking the position of quartermaster general, he has not been assigned to lead the military’s Myanmar Economic Corporation (MEC), which sets him apart from his predecessors. Moreover, he is reportedly linked to the now-removed Moe Myint Tun.

Another potential contender for the commander-in-chief position is Lt. Gen. Ko Ko Oo (DSA 38), present commander of Bureau of Special Operation (BSO) No. 1. In 2020, he was appointed to command the Central Military Command in Mandalay with the rank of brigadier general, he was only 45 and the youngest commander of a military regional command. He became head of BSO No. 1 in August 2023. Previously, he commanded the military chief of staff and Military Operation Command (MOC). He is reportedly the son of former deputy minister of President Office No. 4, U Aung Thein, in U Thein Sein’s administration.

Lt. Gen. Thet Pon (DSA 29), the present commander of BSO. No. 5 is another possible successor. He is currently commanding in Yangon. He was honored for his performance on the 2020 National Independence Day. But as he was leading the forces to violently crush peaceful protestors, sanctions were imposed upon him by the governments of the European Union and Canada. But he is unlikely to be selected because of his rather old age. According to the SAC’s Protocol, another important possible contender is Lt. Gen. Ye Win Oo (OTS 77), who is currently the SAC’s joint secretary and commander of Military Affairs Security (MAS). According to the official seating plan, he seems to be on the front line and quite stable in the SAC. Nevertheless, in Myanmar military tradition, commanders of auxiliary forces rarely become commanders-in-chief, but rather, it is most often infantry commanders that come to this highest position. He is now 57.

Yet, military commanders junior to Lt. Gen. Kyaw Swa Lin (DSA 35) could also be selected as commanders-in-chief to be. BSO No. 4 Commander, Lt. Gen. Nyunt Win Swe (DSA 36), should be on watch lists. If the successor selection reaches this point, there will be a widening generation gap in the military. Once, there was an 18- or 19-year gap in the military cadet generation, between Snr. Gen. Than Shwe and Min Aung Hlaing, and the gap between Snr. Gen. Min Aung Hlaing and the next commander-in-chief will be at least 17 years. The younger officers will find it very difficult to raise questions to the present commanders in charge of the military.

In case, if there were some senior officers selected to be the next commander-in-chief, it is customary to nurture them at least three years in service and it may take time. The present commander-in-chief may groom these officers until he is satisfied. Then the time frame of the military succession will conflict with the speculating election timeline in 2025. Min Aung Hlaing’s dream to shift his career to politics could take longer if he is to leave his military chief post in good hands. At this moment, Myanmar’s military faces tremendous challenges in its legitimacy, in its centrality, in its performance, in its guardian role, and in its popular support.

Last, but not the least, there is an interesting point for military leadership. When the military staged a coup in 1988, the head of SLORC/SPDC, Snr. Gen. Than Shwe, was 48 and Secretary, Gen. Khin Nyunt was in 40s. At the time of 2021 coup, Snr. Gen. Min Aung Hlaing was 66 (presently, he is 68). This could be interpreted as a large difference in age. The current heads of the SAC could lack in proactivity, aggression, attentiveness, and innovation, compared to the junta leaders of SLORC/SPDC in the past. As people age, they become more conservative and resistant to change. Current senior military commanders may want to retire peacefully at ease after their terms. They could be hardly become change makers. As time progresses, the military succession crisis and the deepening generational gap will assume increasing significance.

3.Extreme Weather and Acute Flooding in Myanmar

Soon after the commencement of the extreme weather phenomenon of El Niño, some areas of Myanmar experienced acute floods. In Bago City, the water level reached 940 cm on October 9, above the “danger level” of 880cm. In three days of flooding, fifteen wards and nine villages (80 percent of the city) were inundated, amounting to the worst flooding in 60 years, affecting 13,000 people. News reported that in addition to Bago City, Hmawbi, Taik-Kyi, Kyaik Hto townships and some places on the Yangon–Mandalay highway and railway were underwater.

During the El Niño phenomenon, extreme weather can cause drought, extreme heat and floods in various places, which can damage crops. In SAC’s official newspaper, the SAC officials explain the nature of El Niño to the public in many townships. However, this is not enough, and many preparations should be made on the side of the authorities, such as disaster preparedness, the empowerment of the population, climate-sensitive budgeting, and linking to international humanitarian agencies and climate diplomacy.

During the last year of the U Thein Sein administration, in July and August 2015 (during the previous El Niño phenomenon), floods inflicted extensive damage in Myanmar: twelve out of 14 states and regions were inundated, affecting a million people. Myanmar faces the problem of flooding almost every year and some years are much worse than others. In 2015, some estimated that Myanmar could lose two percent of its GDP because of flooding. For coming natural emergencies, the mantra of “self-help” is not enough: more preparation is required.

∎ Trends to be watched

Widespread Corruption in Myanmar

To understand the post-coup insight into Myanmar’s society, ISP-Myanmar conducted a socio-economic study in 110 townships to identify the SAC’s performance of public services in the three months of May, June, and July 2023. One question in the study was whether it is necessary to pay bribes to township-level officials to get things done. The findings indicated that it is required to pay cash bribes to township officials in 70 to 107 out of 110 townships observed (64 to 97 percent). It is common for people to have to pay gifts to officials and staff in exchange for the public services they receive.

The study observed the SAC’s municipal, tax office, immigration office, electricity supply office, education, hospitals, and administration offices in terms of taking bribes. According to the July findings, people need to pay immigration officials in 109 townships out of 110 townships observed. The second most corruption-ridden offices are municipal, courts and administration offices. The survey result shows people use money to pay bribes in 103 out of 110 townships surveyed. The office that is most likely to accept gifts, rather than money, as bribes is the education department; this was reported by 57 out of 110 townships in May, and this increased to 76 townships in June and July. Another office likely to accept gifts as bribes is the township court; this was observed in 55 townships in May, and 69 townships in June and July.

It is conspicuous that people use gold to pay bribes. It was found that people pay gold as a bribe to township court officials in nine townships in May, eight townships in June, and nine townships in July. Survey results found that administration offices were second most likely to accept gold jewelry; this was reported by six townships in May, two townships in June, and four townships in July, respectively. The tax offices are the third most likely to accept gold: three townships reported this in May, three townships reported this in June, and four townships reported this in July.

The least corrupted departments were found to be hospitals. This was reported by 25 townships in May, 22 townships in June, and 19 townships in July. This was followed by electricity supply offices, as reported by 18 townships in May, 24 townships in June, and 21 townships in July.

According to Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) (2022), Myanmar received a score of 23 out of a range from 0 (“highly corrupt”) to 100 (“very clean”). Myanmar ranked 157th out of the 180 countries in the Index. What the results of the ISP-Myanmar’s survey show is the ‘petty corruption’ present among public servants working at the township level. However, the bribe payments involve gold and cannot be underestimated as petty. It is presumable there could be “policy-level corruption” at higher levels of administration. The recent SAC’s actions taken against Lt. Gen. Moe Myint Tun, Brig. Gen. Yan Naung Soe and other officers may be a good example. However, ISP-Myanmar’s survey findings cannot reveal the corruption of such “big fish”. Academic studies suggested there will be more corruption if there is a combination of a “monopoly of power” and the “discretion of officials” while lacking “accountability.”

In post-coup Myanmar, check-and-balance mechanisms are dysfunctional, as no parliamentary representatives question public services, and there is a very limited and risky role of activists and the media. On the other hand, the pay given to public servants hardly rises in accordance with rapidly increasing inflation and commodity prices. Because of inflation, their spending power is largely dwindling. This trend will inevitably drive these public servants to compensate for their falling standard of living with corruption.

∎ What ISP is reading?

ILO’s Investigation Report and Potential Bigger Impacts on Myanmar

ILO. (August 4, 2023). Towards Freedom and Dignity in Myanmar. 207 pages

A few days ago, the International Labor Organization (ILO) published an investigation report on Myanmar. In June 2021, after the military coup in Myanmar, the ILO called upon the military to restore democracy and respect its citizens’ human rights. At the 344th governing body meeting of Switzerland’s Geneva-based ILO from March 14 to 26, 2022, it was decided to set up a high-level commission of inquiry with respect of the non-observance by Myanmar of the Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organize Convention, 1948 (No. 87) and the Forced Labor Convention, 1930 (No. 29). The SAC’s Labor Ministry issued a statement on April 4, 2022, strongly rejecting the decision, as it was unilateral.

The Governing Body of the ILO later appointed persons to serve on the Commission of Inquiry: Judge Raul Cano Pangalangan (Philippines) as chairperson and Judge Dhayanithie Pillay (South Africa) and Dr Faustina Pereira (Bangladesh) as members. ILO’s Commission of Inquiry emphasized particularly Convention 87 and Convention 29. The Commission concluded in the report that the military control has “had a disastrous impact on the exercise of basic civil liberties. Trade union members and leaders have been killed, arbitrarily arrested, subjected to sham trials, convicted, detained, abused, and tortured, threatened, intimidated, subjected to surveillance, forced into exile.” In addition, the report of more than 200 pages mentioned with evidence that “women trade union leaders have been exposed to particularly violent treatment on the part of the security apparatus, including sexual violence.”

The ILO’s high-level Commission of Inquiry on Myanmar is the 14th action in its history spanning more than a hundred years. There is a three-month deadline for the Myanmar junta to respond. The Commission has investigated not only the SAC but also the forced labor practices of EAOs in conflict areas, such as the Shan State Army (SSA/SSPP), the Shan State Restoration Council (SSA/RCSS), the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and the Arakan Army (AA).

The SAC Labor Ministry issued a statement mentioning that “Myanmar is a member state of the ILO, complying with ILO Convention No. 87: no one is punished or taken action for practicing his or her rights peacefully or being a member of a trade union. According to the Labor Organization Law (2011), Myanmar granted registrations to over 3,000 organizations – 2,886 basic labor organizations, 162 township labor organizations, 26 region/state labor organizations, nine labor federations, one confederation of trade unions of Myanmar, one basic employers’ organization, one township employers’ organization, and one employers’ federation. More than 190,000 workers are enjoying their rights in these organizations.”

Again, on September 2, 2022, the SAC Labor Ministry strongly rejected the ILO’s website display about Myanmar. A trade unionist assisting with labor issues in Myanmar discussed the ISP-Myanamr for their sandwiched difficulties. Though the SAC claims no official ban on trade unions, the most restrictive new organization law makes it difficult to be registered. These labor campaigners are not collaborating with higher-level ministries, but they are assisting garment workers with township-level officers to mediate industrial conflicts with factory owners and laborers when there were protests and sit-ins to demand pay raises and healthier worksites. Then, they faced criticism from exiles as collaborating with the illegal junta. In the post-coup situation, tripartite negotiations between employers, workers and the government and industrial arbitration have stopped. The SAC announced the minimum wage as 5,800 kyats, changed from 4,800 kyats on October 5, 2023. However, it is unilateral and does not follow the 2013 Minimum Wage Law, which requires to set the minimum wage based on the negotiated result of employers, workers, and government representatives. Unquestionably, workers in Myanmar are losing their rights to be represented, to make demands, and to organize themselves in trade unions.

What could happen if the Myanmar junta doesn’t accept the recommendations of the ILO? In the late 1990s, international sanctions against Myanmar were initiated because of forced labor issues, rather than political ones. This time, if the junta commits similar violations as the ILO demands it to stop, or fails to reform according to the recommendations, the ILO refers the matter to the International Court of Justice, the UN’s top court, without passing through the UN Security Council. On the other hand, the trade unions’ actions will be immense and will fight for the rights of workers in Myanmar, which could result in a heavy blow to trade and tourism.

To receive ISP Insight Emails in your inbox, subscribe at this link.